Where does pastrami really come from?

An exclusive Forward culinary investigation employs archival research to debunk a persistent and vexing rumor about a smoked meat’s origin story

Published May 11, 2022

There’s a rumor about history of pastrami. That it’s from Texas, not New York. The idea has been kicking around since 2015, first as wild speculation by a New York food critic, then as probable fact by the magazine Texas Monthly.

If this controversy is news to you, that might be because in most places, pastrami is a rubbery bland pinkish processed meat. Its origins are at most a trivial curiosity. In New York, however, pastrami burns magenta bright and is fatty, sinewy and tender. The meat falls apart in your mouth. It’s nearly sacred.

Where pastrami comes from matters. And more specifically, that pastrami is from New York matters. This isn’t a case of New York food snobbery. I’m not the type who denies there are decent bagels and good pizza west of the Hudson, nor am I a pastrami purist.

When Mile End opened in Brooklyn in 2010 selling “smoked meat,” the Montreal cousin to pastrami, I didn’t hesitate to trade my New York pride for a sandwich. When Mission Chinese made Kung Pao pastrami a thing, I eagerly took chopsticks to the Szechuan pepper-encrusted cured meat. And each time a hipster barbecue spot with pastrami opens in a former warehouse, I’m there with an IPA in hand.

But it’s beyond the pale to suggest that pastrami’s native habitat is white bread and barbecue sauce, not rye and mustard, which is exactly what the Eater and former Village Voice critic Robert Sietsema did in his 2015 book “New York in a Dozen Dishes.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jewish butchers in Texas, he theorized, “might have first decided to experiment with smoking corned beef. And hence might pastrami as we know it have been born.”

Sietsema, who lived in Dallas before moving to New York, based his theory off the research of Daniel Vaughn, the barbecue editor of Texas Monthly, who had found ads for a Corpus Christi Jewish butcher shop selling “Pastromie” in 1916 — decades before anyone thought Texans ate the cured meat. Vaughn then followed up with a deep dive, finding even older references.

Czech and German butchers brought their meat-preserving processes to Texas after immigrating to the United States, and then made their way to the East Coast,” is how Nick Solares of Eater magazine, who covered the topic in 2016, summarized Vaughn’s theory.

What started as Jews possibly inventing pastrami in Texas had slid into questioning whether pastrami was Jewish at all.

Finally, in 2018, barbecue historian Robert Moss tried to put an end to the debate with an article in Serious Eats. Moss was hoping to find evidence that the cured meat was southern in origin, but instead concluded, “pastrami first established its foothold in large northern immigrant centers, like New York, Montreal, and Chicago, and was then taken across the country.”

OK, that’s nice. But is it from New York? The short answer: Pastrami is as New York as traffic on Delancey Street. And is it Jewish? It’s as Jewish as kvetching about the traffic on Delancey Street.

In Search of Historic Pastrami

Food writers have pored over the English language press and antique menus for the origins of pastrami. Thus far, however, they have ignored the vast world of Yiddish newspapers in 19th century America, which show that pastrami first appeared on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Pastrami tells the story of how a new Jewish-American cuisine formed.

First, I’ll admit that for a long time, I also thought pastrami didn’t come from New York.

Growing up, I understood pastrami to be a food of nostalgia. Between sour pickles, my father would remember how, when he was a kid in the 1950s, Sunday night was deli night. His extended family would come over for takeout, giving my grandmother one night off from cooking. Like many American Jews, they had replaced the Friday night Shabbat dinner with a secular Jewish tradition of celery soda and nitrates.

By the time I came around, my family had become hyper-aware of cholesterol. Deli was a frequent but not weekly event. Our go-to spot was Liebman’s in Riverdale in the Bronx. It’s still there, the only deli in New York that smokes their pastrami in-house, and the last surviving deli out of what used to be hundreds in the borough.

Liebman’s, with its neon lights, faux-leather booths, and stainless steel display cases with stuffed peppers and pickled tomatoes, screams midcentury Jewish New York. You can almost hear the smacking of stickballs. Nonetheless, I imagined I was connecting back further to the old country.\

I just assumed my family had been slathering mustard on pastrami and corned beef while comparing their medical procedures for millennia, only switching yarmulkes for Yankee hats along the way.

In truth, whatever my grandmother ate in her dusty village in Belarus on the eve of World War I, it wasn’t much, and it definitely wasn’t thick fatty sandwiches. Meat would have been a rare luxury.

Food historians are clear — there was no pastrami in Europe, but there was pastrama, a tough beef jerky-like Romanian dried meat, which might sound like pastrami but is very different. Romanian Jews most commonly made pastrama by curing, spicing and smoking goose meat. But other variations are found across eastern Europe and into the Caucasus under the names pastram, pastromá, pastirma, basdirma, and basturma. In New York, these pastrami cognates are usually made with beef and can be found in the freezers of ethnic markets in Queens.

These cured meats all derive from a preservation method brought by conquering Ottoman armies. “Turkish horsemen in Central Asia also preserved meat by inserting it in the sides of their saddles,” writes Ted Merwin in his book “Pastrami on Rye,” a history of Jewish delis. “The meat was tenderized in the animal’s sweat.”

The taste of horse perspiration didn’t withstand the test of time, but the spice route origins of pastrami survive in the coriander, paprika and mustard rub.

Merwin, a Judaic studies professor at Dickinson College, says Romanian Jews brought over goose pastrama to New York’s Lower East Side. The poultry meat was switched out for heartier American beef, and the curing process was slowed with refrigeration before the salted and spiced meat was smoked and then rehydrated with steam or braising. The result is the fatty and smoky pastrami now associated with surly deli men.

As others have pointed out, New York’s claim to pastrami lacks hard proof. Two places say they’re the first: the city’s oldest surviving deli, Katz’s, claim they invented it in 1888; and a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant named Sussman Volk swore he was the first in 1887 at his Delancey Street butcher shop turned deli.

In her memoir “Stuffed,” Patricia Volk says her grandfather Sussman received a pastrami recipe from a Romanian Jewish friend. But neither Katz’s nor the Volks offer any proof. Moss, in his Serious Eats article, deeply researched historical and immigration records and argues that neither business could have existed before 1898.

Indeed, on the facade of Katz’s, a “Since 1898” sign has clearly been doctored to read 1888. Katz’s may be fast with the facts on the outside, but inside, it is as much a museum as a restaurant.

The depression-era furniture is well worn, the pastrami is still smoky, savory and a bit sweet, and the countermen who hand-slice it can still be persuaded with a modest tip to stack your sandwich extra high.

Sietsema sings the praises of Katz’s but questions the theory that Romanian pastrama gave way to pastrami in New York, homing in on Romanian steakhouses.

He describes the last great one of the genre, Sammy’s Roumanian on Chrystie Street. The third Romanian steakhouse in that location, it closed during COVID-19. At Sammy’s, Dani Luv, a bawdy Israeli keyboardist, performed Yiddish-inspired parody songs while diners chowed down on fried kreplach and broiled meats — but importantly, not pastrami. Sietsema then explores other steakhouses that combined vaudeville acts and heaping plates of red meat reaching back to Harry Greenberg’s Roumanian Casino, which opened in 1894. He finds chopped liver, “frozen calf’s feet” and carnatzal, a garlicky Romanian sausage, but again, no pastrami.

Which leads him to the question: “But why, if Romanian Jews brought pastrami to the States, was this smoked meat not found in their restaurants?”

An excellent point, except that Romanian-born Jewish author Marcus Ravage in his 1917 memoir “An American in the Making,” waxes nostalgic — “on Rivington Street and on Allen Street the Rumanian delicatessen-store was making its appearance, with its goose-pastrama and kegs of ripe olives.” And the Tenement Museum’s Jane Ziegelman, in her culinary history “97 Orchard Street,” references a 1930 review of Perlman’s Rumanian Rathskellar on Houston Street which mentions “smoked goose pastrami” along with other dishes the reviewer calls “invariably unspellable and wholly delicious.”

Lara Rabinovitch, who co-curated the “I’ll Have What She’s Having”: The Jewish Deli exhibition currently at the Skirball Center in Los Angeles and wrote her Ph.D dissertation on Romanian Jewish immigration, told me pastrami came up often in her historical research on New York’s Little Romania. The other major destination for Romanian Jews was Montreal, which Rabinovitch pointed out is also known for their smoked deli meat.

It was so close to the heart of Romanian Jews that the Yiddish theater star Aaron Lebedeff sings affectionately of “pastramele,” using the diminutive of the smoked meat, in his 1925 hit song “Roumania, Roumania.”

Pastrami’s Deli Roots

Homesick Bucharest emigrés may have been feasting on goose pastrama in their own restaurants, but beef pastrami is the product of the New York delicatessen, an institution forged from the melting pot of the Lower East Side.

The first delicatessens in New York date back to German immigrants in the 1840s. Back then, they were a style of store brought over from Europe. Merwin writes of an early one run by a Berliner on Grand Street, “His shelves brimmed with cooked meats, hard cheeses, fancy canned foods, imported teas, olive oil, and other high-end groceries.” The delicatessens owned by both Christians and Jews doubled as wurst gesheftn (sausage shops).

You can find evidence of the German sausage roots of New York delis in a faded sign outside of Katz’s that reads “Wurst Fabric” (sausage maker). By the end of the 19th century, east European Jews had taken over the delicatessens. They embraced the German beef salami, but most got rid of the hard cheeses, a nod to Jewish dietary rules, even if many were only kosher style.

East European Jews also introduced a hodgepodge of their own traditional dishes. A pan-Ashkenazi cuisine with distinct American influences developed. Eventually, the New York delicatessen as we know it formed: sit-down restaurants with American-style sandwiches that, yes, served pastrami, but didn’t usually prepare it in-house.

The majority of delis have long bought pastrami from kosher meat processors. At the end of the 19th century, the largest suppliers were German Jewish-owned plants on the Lower East Side’s East River shoreline. They would ship the salamis, pickled tongue and liverwurst to a growing number of delis nationwide. One of the largest, M. Zimmermann, is mentioned in one of the earliest references to pastrami cited by Moss, an 1899 advertisement for Stein’s grocery in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

But even before pastrami was being sold to English speakers, it was well established with Yiddish speakers.

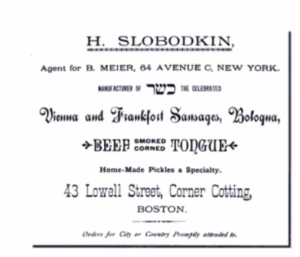

In September 1891, six years before the earliest reference to “pastroma” in a non-Jewish American publication, B. Meier, a sausage and meat factory at 64 Avenue C on the Lower East Side, began to run weekly advertisements in Fraye arbayṭer shṭime (Free Voice of Labor), a Yiddish language anarchist-communist publication. “News! News!” the ad announces before boasting, “B. Meiers is the only manufacturer of the world famous pastrama. Only he knows the code of how it is perfected and all the other pastramas are just imitations.” It then goes on to list an assortment of beef products including salamis, tongue and Vienna sausages.

Within weeks, the German-born Bernhard Meier had competition in New York and Brooklyn. Moses Zimmermann and other meatpackers were advertising “pastrame” and “Romanian pastrama” in Yiddish newspapers.

But what exactly were they making? Unlike today, foodies didn’t tweet out every minor culinary trend in Manhattan. So, it’s hard to know when goose pastrama became New York beef pastrami.

Just as in English, the spelling in Yiddish changes over time. Pastrama (פּאַסטראַמאַ) first dominates in the 1890s, then gives way to pastrame (פּאַסטראַמע) in the early 1900s. Pastrami (פּאַסטראַמי) doesn’t dominate until after World War II. The changes don’t reflect on the ingredients. A Yiddish cookbook first published in New York in 1914 uses the same spelling in recipes for traditional Romanian goose and American beef pastrame.

Court records and factory inspections are also of limited help. They use the catch-all “bologna” for processed meats. Clues are found in B. Meier and M. Zimmermann’s English language ads which consistently list only beef products, not poultry. This suggests that when they advertised in English for smoked beef, they were including pastrami.

Then, in 1894, Meier, now merged business with recent Russian Jewish immigrant George Gerzog, began running bilingual ads in a new English and Yiddish newspaper, The Hebrew American. In the first issue, they advertised in English, “smoked and pickled meats.” The following week, on March 24, 1894, they added to the list, “Roumania Pastroma.” This marks the earliest advertising of pastrami in English. It would be another three years before the cured meat would be named in the English language press, as has been highlighted by Moss.

The only suggestion that these producers were using anything but beef was a 1908 article in the Yiddish language Jewish Morning Journal that accused M. Zimmermann of using horse meat.

Was pastrami really the food of penniless East European ancestors?

I have yet to find a smoking gun in my smoked meat research. It’s still a safe bet that some time after Romanian Jews arrived in New York in 1881, goose pastrama was turned into pastrami by well-established German Jewish meatpackers.

Sietsema and Vaughn seem to doubt this theory because pastrami feels more like a Texan than Jewish Lower East Side dish. As Vaughn told Solares in the Serious Eats interview, “If you look at New York back in those days, there weren’t a lot of meat markets smoking their meat, “something Texas has a long and famed history of doing.

Not only did I find advertisements for German Jewish butchers smoking meat on the Lower East Side going back to 1849, but New York became a point of reference for meat at least among Jews. Montreal Jewish Public Library Emeritus Archivist Eiran Harris cites an 1894 Yiddish ad for “Montreal’s largest butcher shop,” which promises its products, including smoked meats, to be the “same quality as New York.”

Still, Sietsema and Vaughn are keen eaters and have a point. A thick pastrami sandwich seems more like the lunch of a bulky rancher than a striving garment worker.

Indeed, many Jewish Americans make the wrong assumption, like I once did, that pastrami was the everyday food of even our penniless ancestors. This naturally leads to the common complaint: what was once peasant food goes for $24.95 at Katz’s.

It’s true the cuts of navel and deckle used for pastrami have gotten expensive, but they were never cheap. In 1902, the price of kosher meat increased from 12 cents to 18 cents per pound, the equivalent of $6 today. In the 1920s, a pastrami sandwich at the trendy Reuben’s deli in Times Square cost $1, or over $15 today.

That the cured meat was an extravagance within reach and something you couldn’t prepare at home was the point. In her book “Hungering for America” about immigrant foodways, Hasia Diner writes, “For east European Jewish immigrants, America was a land not just of “milk and honey” but of meat and cake and ice cream — indeed, of seemingly limitless food possibilities.”

The Forward in 1903 printed a new Yiddish word oyesessen, meaning to dine out. It described a growing trend among assimilating Jewish immigrants. To go out to a deli and devour a sandwich thick with meat was a way for Jews to show they made it in America.

Perhaps those garment workers would be happy to know that a century later they would be confused for Texans.