The ordination of the first female rabbi 50 years ago has brought many changes – and some challenges

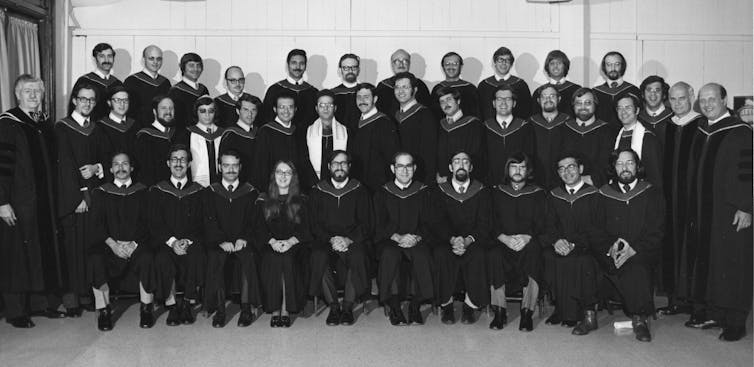

Sara Hurwitz, Amy Eilberg, Sandy Eisenberg Sasso and Sally J. Priesand, each of whom was the first female rabbi in her branch of Judaism. Courtesy of The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives

Published June 3, 2022

Fifty years ago, on June 3, 1972, as Sally J. Priesand became the first woman ordained a rabbi by a Jewish seminary, her 35 male classmates spontaneously rose to their feet to acknowledge her historic feat.

For nearly 2,000 years, the position of rabbi – which literally means “my master” or “my teacher” – was limited to men. The only exception during all those years had been Rabbi Regina Jonas, who was ordained in a private ceremony in Germany in 1935. Jonas perished at Auschwitz in 1944, and the details of her life were discovered in archives after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Thirty-seven years after Jonas’ pioneering first, Rabbi Priesand’s ordination by Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the seminary of Reform Judaism, the largest denomination of religious affiliation among American Jews, opened the door to hundreds of women becoming rabbis.

ADVERTISEMENT

As a rabbi and historian of Jewish women in the modern era, I know that while the advent of women as ordained religious leaders has changed the face of the rabbinate, the values of equity and justice codified in the Hebrew Bible have not yet been fully realized when it comes to gender.

Making a difference

The rise and integration of women into the rabbinate over the past five decades has transformed many aspects of Jewish life, especially in North America, where they primarily serve. A smaller number are employed in Israel, Europe and Australia.

Courtesy of The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, CC BY

An estimated 1,500 women have become rabbis across every major Jewish denomination. After Rabbi Priesand in 1972, Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso was the first in the Reconstructionist movement in 1974, Rabbi Amy Eilberg in the Conservative movement in 1985 and Rabba Sara Hurwitz in Modern Orthodoxy in 2009.

The use of the professional title “rabbi” for an ordained woman remains controversial among Orthodox Jews as it derives from the masculine Hebrew word “rav,” the title given to men at ordination. As a result, some use “rabba,” the feminine rendering of “rav” in Hebrew, while others use “maharat,” a Hebrew acronym for a female leader of Jewish law, spirituality and Torah.

ADVERTISEMENT

Classes at liberal Jewish seminaries today often consist of at least equal numbers of male- and female-identifying rabbinical candidates. Maharat in New York City was founded in 2009 as the first institute to ordain women to serve as Orthodox clergy. Over 50 women have been ordained since then.

Along with female academics, female rabbis have expanded the canon of Jewish study and stretched the parameters of Jewish practice to include women and their perspectives.

New commentary based on the Torah – which means Jewish learning in general but refers literally to the first five books of the Bible contained in the scroll regularly read in synagogue – has recovered the stories of biblical women and treated them with the academic rigor usually reserved for biblical men. Women, alongside men, are studying classical legal texts and responding knowledgeably to questions that inform practice.

Feminist Jewish theologians have questioned the ways in which God

is described and understood, challenging the centrality of both male imagery and hierarchy in Jewish religious thinking and leading to the production of prayer books with gender-inclusive language.

Moreover, female rabbis have been instrumental in creating rituals to acknowledge milestones relating to women’s experiences. So, for instance, baby namings welcoming girls into the covenant now coexist alongside those for boys, and new religious ceremonies marking the first menstrual period and menopause have emerged.

By dint of their presence as religious authorities, female rabbis are toppling the traditional gendered differentiation of roles between Jewish women and men and democratizing Jewish communities. In Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist Judaism, for instance, women are no longer relegated to lighting candles and men alone privileged with reciting Kiddush, the blessing over the wine, on the Jewish Sabbath. Female scholar-rabbis now teach and, in some cases, lead seminaries, like Boston’s Hebrew College and New York’s Jewish Theological Seminary.

They are also challenging conventional definitions of professional success by raising questions about work-life balance pertinent to all rabbis, regardless of gender.

Fighting for equality

While their impact on Jewish life has been significant, female rabbis continue to face considerable challenges.

Teams deployed to Reform synagogues in the early 1980s to interview Jews about their qualms regarding female rabbis’ initial entry into the workplace yielded comments such as “the rigors of the rabbinate are too great and women too weak for the demanding routine,” “women do not know how to, nor care to, wield power or authority” and “women who succeed will reflect poorly on their [male] colleagues.” These have given way to far more egregious claims of gender discrimination and sexual misconduct at seminaries and synagogues in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

Equity in the Jewish workplace has yet to materialize. There is, for instance, an 18% gender-based wage gap among Reform rabbis in congregations. The acceptance of female rabbis in Orthodox Judaism remains highly contested. The Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America continues to reiterate its opposition to ordaining women. For sectors further to the right, like the ultra-Orthodox Hasidim, affirmations of male and female difference make the question of women rabbis moot.

Organizations like the Women’s Rabbinic Network and the three-year-old grassroots Facebook group known as Year of the Jewish Woman are seeking to root out inequities. Plans to thoroughly revise the ethics code of Reform rabbis have been set in motion, and the Women’s Rabbinic Network continues to advocate for passage of a uniform family and medical leave policy.

‘Little girls can grow up knowing they can be rabbis’

The truth is that the days of a rabbi envisioned as a white man with a beard in a dark suit are coming to a close.

In more recent years, the diversity engendered by women in the rabbinate has expanded to include rabbis of color, rabbis with disabilities, openly gay rabbis and transgender rabbis. In May 2022, the Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion issued a certificate of ordination to a nonbinary candidate for the first time in its 147-year history.

When Rabbi Michelle Missaghieh appeared on the long-running medical television drama “Grey’s Anatomy” in 2005 (as herself), and Jacqueline Mates-Muchin, who is the first Chinese American rabbi, addressed the Democratic National Convention’s Jewish American Community Meeting in 2020, they were smashing the so-called stained-glass ceiling and enabling all Jews to consider the rabbinate as a calling.

As Priesand told me during an interview in May 2021, “One of the things I’ve always been proudest of is that little girls can grow up knowing they could be rabbis if they want to. And I’ve worked really hard not just to open the door but to hold it open for others to follow in my footsteps.”![]()

Carole B. Balin, Professor Emerita of Jewish History, Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.