With fewer survivors around, Holocaust education is in transition

Published April 14, 2015

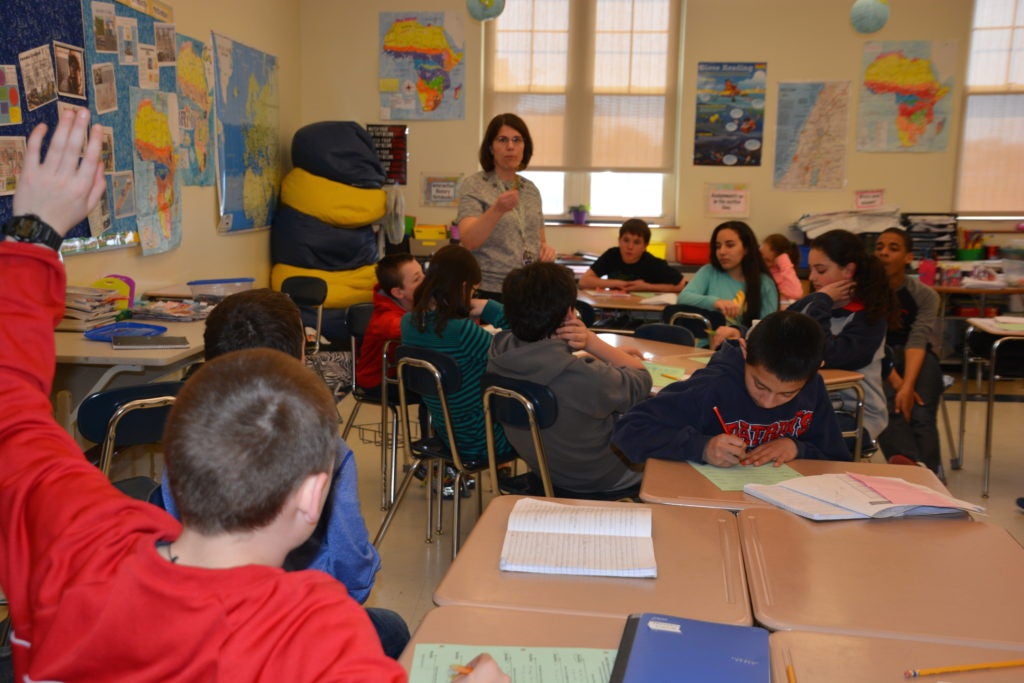

Tracy Sockalosky leading a discussion with her seventh-grade class at Wilson Middle School in Natick, Massachusetts. (Courtesy of Tracy Sockalosky)

BOSTON (JTA) – On a recent morning, a group of seventh-graders in Natick, Massachusetts, was absorbed in a video of Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel’s acceptance speech of the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize.

“Why did he win?” asked their teacher, Tracy Sockalosky.

She guided the discussion to the importance of remembrance, a theme reflected in Wiesel’s book “Night,” which the class had read earlier in the year as part of an eight-week unit on the Holocaust that Sockalosky co-teaches with a colleague.

Sockalosky, a 39-year-old history and world geography teacher at Natick’s Wilson Middle School, was one of 25 educators from around the world who traveled to Poland in January for the commemoration ceremonies of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. The five-day trip, organized by the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation-the Institute for Visual History and Education, in partnership with Discovery Education, included workshops at Warsaw’s new Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, visits to Jewish historical sites and meetings with survivors.

A webcast produced during the trip, “Auschwitz: The Past is Present Virtual Experience,” will be made available to teachers and students in grades 9-12 on May 13 through the foundation’s recent partnership with Discovery Education, a company that streams educational content to teachers and classrooms across the country.

With the last cohort of survivors in their final years, Holocaust education, which once relied heavily on classroom visits from survivors, is in a period of transition.

“We’re on the cusp of a shift,” when it will no longer be easy to find survivors to speak directly with students, says Roger Brooks, president of Facing History and Ourselves, a Boston-based nonprofit that offers multidisciplinary professional development, curricula and resources for teaching about the Holocaust and other genocides.

Founded in 1976, Facing History, which now has programs in 150 locations around the world including Northern Ireland, Israel, South Africa and China, combines teaching the history of the Holocaust with readings that explore ethics and questions of civic responsibilities. Its Center for Jewish Education, started in 1990, works with educators in more than 750 Jewish educational settings, including about 100 day schools.

While no one knows how many schools in the United States teach about the Holocaust — it’s a topic the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington is hoping to study at some point, officials there say — people in the field sense it has become more of a mainstream phenomenon in public, private and parochial schools all over the country, even in communities that lack significant Jewish populations.

Five states — New Jersey, New York, California, Illinois and Florida — have some type of mandate to teach about the Holocaust in public K-12 schools, according to Peter Fredlake, director of teacher education at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Others encourage Holocaust education or make curricular recommendations.

But approach, quality and goals vary dramatically, Fredlake and others in the field say, with some schools teaching the Holocaust strictly for its historical significance and others with hopes of imparting lessons about civic responsibility and the dangers of intolerance.

Meanwhile, more than 80 groups throughout the United States offer resources and training for Holocaust educators, according to the U.S. Holocaust museum. A new museum in Brooklyn, the Kleinman Family Holocaust Education Center, is the first to focus on the experience of Orthodox Jews in the Holocaust.

Many are grappling with how to teach about the Holocaust in a post-survivor age.

For the past 20 years, in anticipation of the shift, USC’s Shoah Foundation has collected more than 52,000 testimonies of Holocaust survivors for its Visual History Archive. More than 1,500 of the testimonies are included in the foundation’s IWitness, a program designed for classroom use that enables students to stream video and audio testimonies and create their own multimedia presentations. The program reaches some 39,000 educators, and the January trip, in addition to seeking to deepen teachers’ understanding of the historical landscape of Poland before and after the Holocaust, sought to promote the use of the IWitness program.

“This is really bringing the power of storytelling in the digital environment,” according to Kori Street, director of education at the Shoah Foundation. “It’s putting a human face to history.”

Testimonies can’t be presented on their own, however, Street and others caution. Instead, they say, testimonies must be supplemented with lessons about the context of anti-Semitism and the history that led to the Holocaust.

By “looking at the small and insidious steps as they unfold, it helps students learn about warning signs, and to recognize and respond to them in their own lifetimes,” says Jan Darsa, director of Facing History’s Jewish education program.

At its best, says Simone Schweber, the Goodman professor of education and Jewish studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison whose research has focused on Holocaust education, teaching the Holocaust challenges students to examine their own deeply held ideas.

“It’s really hard to do,” she acknowledges, noting that students don’t always construct the moral lessons that their teachers assume, particularly if they bring in stereotypes and preconceptions that go unaddressed.

Sarah Cushman, academic program liaison officer at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, says, “People assume that if you teach [about the Holocaust], students will understand that they shouldn’t bully. There’s a disconnect between what’s being asked of this history and what students are getting from it.”

“The lessons must be made more explicit,” she suggests.

Sockalosky, the suburban Boston teacher, acknowledges that the material she has presented to her students requires high-level critical thinking skills and can be challenging for seventh-graders. But the experience of standing with survivors at the gates of Auschwitz in January has deepened her commitment to reaching students at the level they are at, she says.

“I have to find a way to make learning about the Holocaust not just another historical event we study,” Sockalosky says. “It’s not just about the history; it’s about the human experience.”

![]()