Orthodox women are using Instagram to fight racism, on and offline

Published June 9, 2020

(JTA) – Shevi Samet started her Instagram livestream by letting out a long, deep breath.

“How are you?” she asked her co-presenter and fellow Instagrammer Shoshana Greenwald.

“So, so nervous,” Greenwald replied.

“So nervous, so nervous,” Samet echoed. “I just want to address that briefly: Shoshana and I are literally doing this with our hearts in our throats.”

The two women were about to begin an hourlong discussion of racism and their journeys in learning more about anti-racism education through Instagram. The Orthodox Jewish mothers had thought about organizing a discussion like this for months. But after the killing of George Floyd, a black man who was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis, and the protests that unfolded in response, they felt they needed to speak up about racism even more fiercely – and finally, people were listening.

“Something is happening,” Greenwald told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I feel like I’ve been here shouting, like fellow Jews we need to confront our racism! And all of a sudden I feel like people in my community are starting to hear it.”

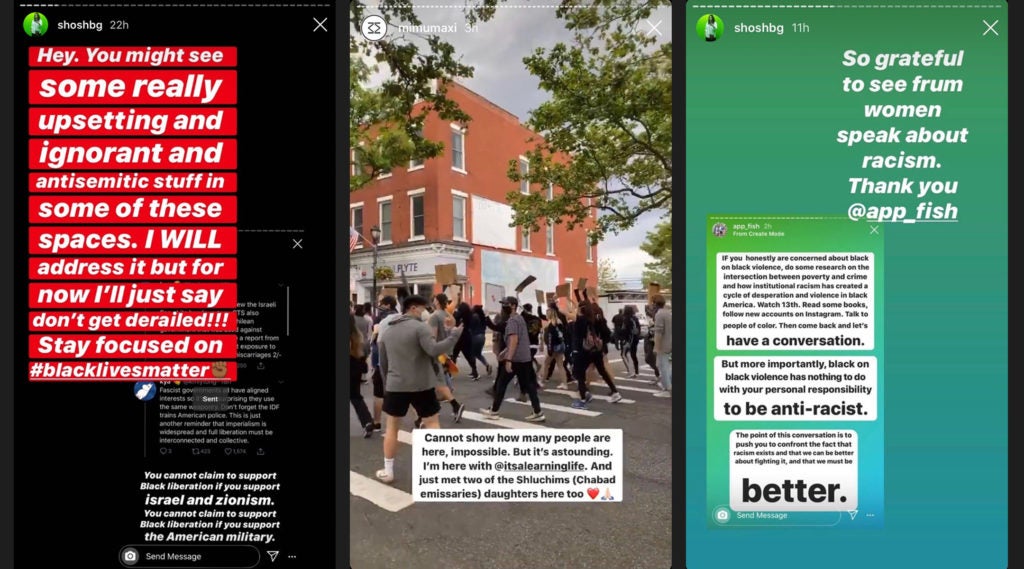

The last week has seen numerous examples of Orthodox Jews joining the national conversation on race sparked by the Floyd protests. Orthodox Jews in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, organized a protest Sunday, one week after an Orthodox man marched arm in arm with two black elected leaders at a protest in Queens. But perhaps the most visible and extensive evidence of the shift is coming on Instagram, the visual social media network favored by many Orthodox Jewish women.

The platform has long served as a gathering place for women to talk among themselves, sharing moments of grief and joy as well as recipes and modest fashion tips. Connections forged there in simpler times are now turning into pathways for challenging discussions about race and where Jews fit in, with a small cohort of women leading the way.

Many of them see themselves as reluctant activists, drawn to serving as conduits to black educators and writers for their insular communities.

“We think of this whole livestream as a ‘b’dieved,’” Samet said at the beginning of her conversation with Greenwald, using an Aramaic term used in discussions of Jewish law to refer to a non-ideal situation.

Greenwald traces her awakening to a moment two years ago when she happened on a post by a black woman named Rachel Cargle. Cargle, a public intellectual and lecturer who hit 1 million followers on Instagram this week, frequently posts images and stories about white supremacy and anti-racism education in the United States.

“I did an incredibly uncomfortable deep dive … it was a very difficult awakening for me,” Greenwald said.

She started doing research about the history of white supremacy in America, reading books and articles about anti-racism and following other black educators on Instagram. The research led her to become more outspoken about racism, both in her life offline and on her Instagram.

“I found that it was a privilege for me to not speak up about racism,” Greenwald said.

Not long after beginning her research on anti-racism, she stopped posting pictures of her children to her Instagram page and started posting exclusively about fighting racism and anti-Semitism.

Samet’s awakening followed a similar path. An educator, she originally used Instagram as a way to share lessons about the Torah. But she quickly came to see Instagram as a way to learn “from people who I would not normally have the opportunity to meet in my relatively insular life.”

She started exploring accounts with a focus on body positivity and intuitive eating and soon found herself following a number of black women who posted about their experiences with racism. Soon Samet was following black activists and educators like Cargle.

“It’s so easy in the frum community to say what does this have to do with me, this isn’t my problem,” Samet said. “I feel like where you have privilege you have responsibility.”

The Orthodox community is insular by nature and mostly white. For those who live most of their lives within the community – living among Orthodox Jews, shopping in Orthodox neighborhoods or at kosher stores, and working with other Orthodox Jews – they may rarely have a significant interaction with a person of color.

“The insular nature of the frum community really contributes to the racist ideologies I see being shared in the community, and people think it’s OK because it’s culturally accepted,” Samet said.

She gave an example of the way her peers talk about their housekeepers.

“Like, oh my lady’s available, do you want her? You can’t lend her out, you can ask her if she’s interested in additional hours of labor,” Samet said. “But you can’t pass her around like an object.”

Like Greenwald and Samet, Chaya Appel-Fishman, a lawyer and mother, has been using her account to amplify black voices. In a story from a week ago, she gave suggestions on how to be anti-racist, like explaining to those who make derogatory comments about black people why their comments were inappropriate, and how the Yiddish word for a black person was disparaging.

“I use this platform to talk about (mostly) what it’s like to be an observant career woman and mommy,” she wrote in one image last week. “So all this talk now about racism and social justice is really throwing some people for a loop.”

Mimi Hecht, a founder of the modest fashion brand Mimu Maxi, posted a picture of herself at a rally last week in Nyack, New York, as well as a number of stories about racism and the Jewish community. She noted her own discomfort with discussing the topic.

“This is not a Jewish issue. Just because I am sharing this as a Jewish woman, and as much as my personal identity inevitably plays a role in how I address this, racism is a cultural, societal, and systemic issue that goes way beyond any one community,” she wrote.

The four women and others sometimes intersect in the comments sections of each other’s posts, or on others posted by Orthodox women weighing in on the protests.

After one account, JewishWomentalk, posted a criticism of Blackout Tuesday, the day when many Instagram users turned their feeds into statements of support for black Americans, Greenwald responded firmly.

“This post is devoid of empathy,” she wrote. “This is about Black people being targeted and murdered. Yes Jewish people are scapegoated too but this is not about us.”

Both Samet and Greenwald said they had faced pushback for their speaking out about racism in the Orthodox community. Greenwald said it had been socially isolating at times being known in her politically conservative community in Brooklyn as the liberal one. Both women have received critical comments and messages in response to their posts about racism.

“People will say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know you were so liberal,’” Samet said.

Still, Samet believes that Orthodox women may be more open to changing their perspectives because they tend to have more positive interactions with other women of color than Orthodox men. She pointed to her own experiences having long, personal conversations with nurses at the hospital where she gave birth to her children.

“I don’t know that my husband’s ever had that opportunity, just because his circles just run differently,” she said.

Samet and Greenwald said sensitivity around anti-Semitism can sometimes make it harder for Jews to confront their own racism.

“I had also thought that as a Jewish person, every generation going back had been persecuted and my ancestors hadn’t enslaved anyone, so I was exempt,” said Greenberg, who works at a Holocaust museum. “Whether I like it or not, I benefit from white privilege.”

Greenberg frequently posts about anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism she has encountered in the social justice world. Samet said she has warned several people about it as they delve deeper into those kinds of accounts.

“I have to admit that it can be a huge turnoff,” Samet said.

But they also view their role as helping Orthodox women understand how to enter social justice spaces respectfully. They suggested that followers reach out to them with questions rather than reaching out to black women at the moment.

“You quiet yourself, you quietly listen, you read the room, you see where the person is coming from,” Greenberg said in the livestream.

“If there’s a term you don’t understand, if you have Instagram, you have Google,” Samet added. “Don’t go into the comments and ask what is this.”

For both women, their Jewishness is inherently connected to the need to fight racism – and their decision to speak up about it, even when it’s uncomfortable.

“’Tzedek tzedek tirdof,’” Samet said, quoting the Hebrew verse that means “justice, justice, you shall pursue.” “That mandate to pursue justice, it’s not like oh when you see justice, wave hi at justice, it’s like pursue it. That’s active, that’s not passive.”