John Eaves wants to be the first black and Jewish member of Congress

Published June 1, 2020

(JTA) — John Eaves can name plenty of people in Congress who look like him. And there’s a fair share who share his faith. But not a single lawmaker shares his two identities: an African-American and a Jew.

Eaves, who previously served as county commissioner of Fulton County, Georgia, hopes to break that barrier by running to represent the state’s 7th District in Congress.

“I’m putting forth a Herculean effort to have a voice in Congress, and I think it would be a unique space that I will fill, so I’m excited,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I’m working hard to get there, and I think that certainly there are Jews and African-Americans, of course, in Congress, but I can walk in both camps.”

Being a member of two minority groups has informed his values and desire to fight for change. As county commissioner he ran programs to reduce homelessness and HIV, and his congressional platform is centered on issues such as ending the gender wage gap, curbing gun violence and pursuing criminal justice reform. If elected, Eaves is planning to join the black-Jewish caucus in Congress.

“You become a little bit of a double target, but you also become doubly sensitive,” he said of being black and Jewish. “That means that I am also hypersensitive to issues of anti-Semitism or racism. I feel that it is just completely unacceptable to deny somebody’s humanity because they are slightly different from the majority for one reason or another. Issues of fairness and justice are very important to me.”

The recent death of George Floyd, a black man, while in police custody and its aftermath have strengthened Eaves’ commitment to political change. Eaves spent the weekend attending a protest and prayer rally and canvassing around Atlanta.

“I saw a couple things — people who were there to support or to vent, but also looking for constructive ways to get engaged and have positive change,” he said. “So it affirmed that what I’m trying to do politically is addressing problems that these protesters are voicing.”

Eaves, who lives in the Atlanta suburb of Peachtree Corners, is among a crowded field of Democrats who entered the race after the incumbent Republican, Rob Woodall, said he would not seek reelection. The district is located north of Atlanta and has become more racially diverse in recent years.

Among some of the high-profile hopefuls are Nabilah Islam, who has been endorsed by progressive Democrats Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar, and Carolyn Bordeaux, who narrowly lost to Woodall in 2018 and is supported by more centrist party members like Reps. John Lewis and Hakeem Jeffries.

Though Eaves, 58, isn’t the most high-profile candidate, he said he is “cautiously optimistic” that he will be one of the two Democrats in the primary on June 9 to qualify for a runoff ahead of the general election in November.

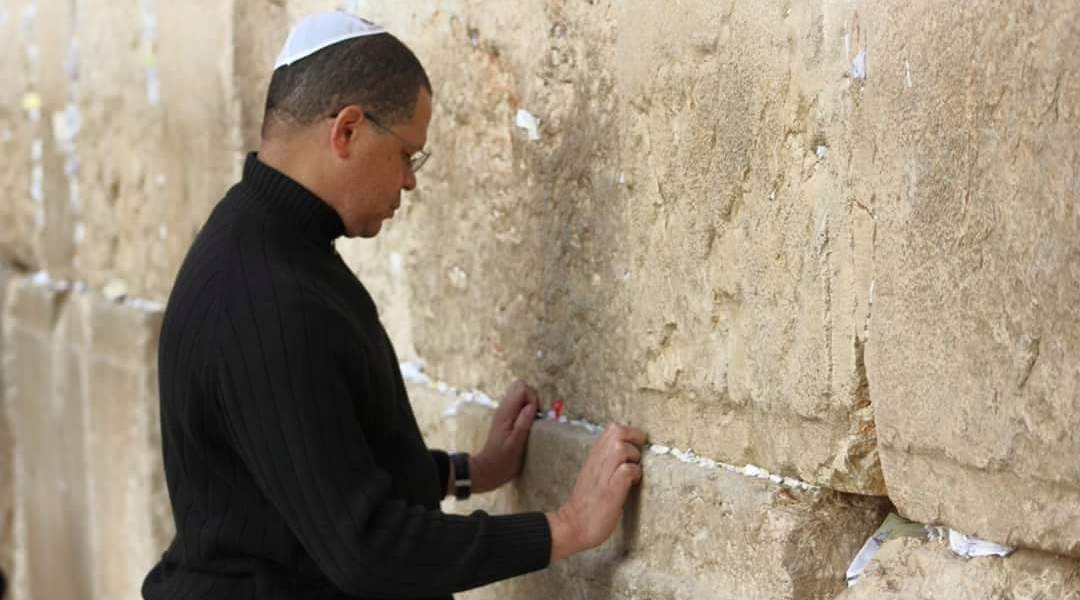

Eaves, seen on a visit to Israel’s Western Wall, says being black and Jewish has made him more attuned to bigotry. (Courtesy of Eaves)

His family has been practicing Judaism for three generations, since his Jamaican-born grandfather embraced the religion after moving to the United States.

Growing up, the family was traditionally observant and attended a black Israelite congregation in Jacksonville, Florida. The black or Hebrew Israelite movement is made up of African-Americans who consider themselves Jewish. Adherents subscribe to a range of religious views and traditions, with some closely mirroring those of regular synagogues while others differ greatly.

Growing up, peers would often ask Eaves about his background.

“I always got the question ‘How can you be black and Jewish?’” he recalled.

Today Eaves is affiliated with The Temple, a historic Reform synagogue in Atlanta, where he has served on the board and now chairs its racial justice committee. Known for its historic civil rights activism, the synagogue was bombed in 1958 by white supremacists.

In his role on the racial justice committee, Eaves organized two events where judges helped expunge the records of hundreds of people with minor convictions. He also helped organize a synagogue trip to the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, which tells the history of slavery and racism in the country.

“He’s really one of the smartest, most thoughtful, caring leaders that I know,” Rabbi Peter Berg said. “He leads with his mind and his heart at the same time, and he has helped us to take our racial justice work to the next level.”

Eaves has an eclectic and impressive resume. He received a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Morehouse College, where he was captain of the football team. He went on to earn a master’s degree in religion at Yale and a doctorate in educational administration from the University of South Carolina.

He spent time in Germany and Finland on Fulbright Fellowships and served as a regional Peace Corps manager. Currently he runs the Global Youth Ambassadors Program, a leadership program for underserved Atlanta high school students, and is an instructor at Spelman, a historically black women’s college.

He traces his desire to enter politics to his late uncle, Reginald Eaves, who broke racial barriers in Atlanta when he became the first black police chief and public safety officer. (Reginald Eaves resigned from the latter role after he was accused of helping officers cheat on exams and served a prison sentence for extortion.)

Like his uncle, Eaves wants to break barriers. That includes challenging perceptions of what a Jew looks like. Though he’s deeply involved in his synagogue, he sometimes encounters people who treat him as if he is a non-Jewish visitor.

“Every now and then I walk in and somebody who doesn’t know me will say, ‘Welcome to Shabbat services,’ and I just politely tell them I’m a member here and I’m also a former member of the trustee board,” he said.

But he is seeing improvement in recent years, which he attributes to a greater number of nonwhite people participating in Jewish communities and an increased effort by local and national community leaders to educate about and promote diversity.

“The past five years or so there has certainly been a recognition that Judaism should have more people under the tent than it has right now and we can do a better job to make people feel welcome,” he said.

But Eaves says more can still be done, particularly when it comes to talking about how Jews in many cases have been perceived as white in American society and the benefits that come along with that.

“Sometimes race and sensitivity is a painful process where you have to face up to your own biases, and it’s dealt with in a way that you can’t run away from it. It’s a tough conversation,” he said.

Eaves also hopes that progress will eventually mean less of a focus on people’s differences. Though he doesn’t mind being referred to as a Jew of color, he hopes the distinction will be unnecessary at some point.

“If you attend Mass at a Catholic place and it’s black and white people there, do you say the Catholics of color?” he asked.

“But within Judaism, there’s a designation of Jews of color, whereas in other faiths you don’t necessarily have that. And I get it right now because there is a degree of evolution that’s occurring in terms of the presence from a racial standpoint of people who may not necessarily look like most of the folks who’ve been there for a long time. But at some point does that go away and we’re just the members of the congregation?”

Eaves ultimately hopes that his run for office can accelerate that evolution. His election, he said, would send a powerful signal.

“It’s a big deal in terms of a public display of the diversity of Judaism, of the diversity of Jews,” he said, “so yeah there are people who are black and Jewish — good people — but doggone it you now have a member of Congress who is in this space.”