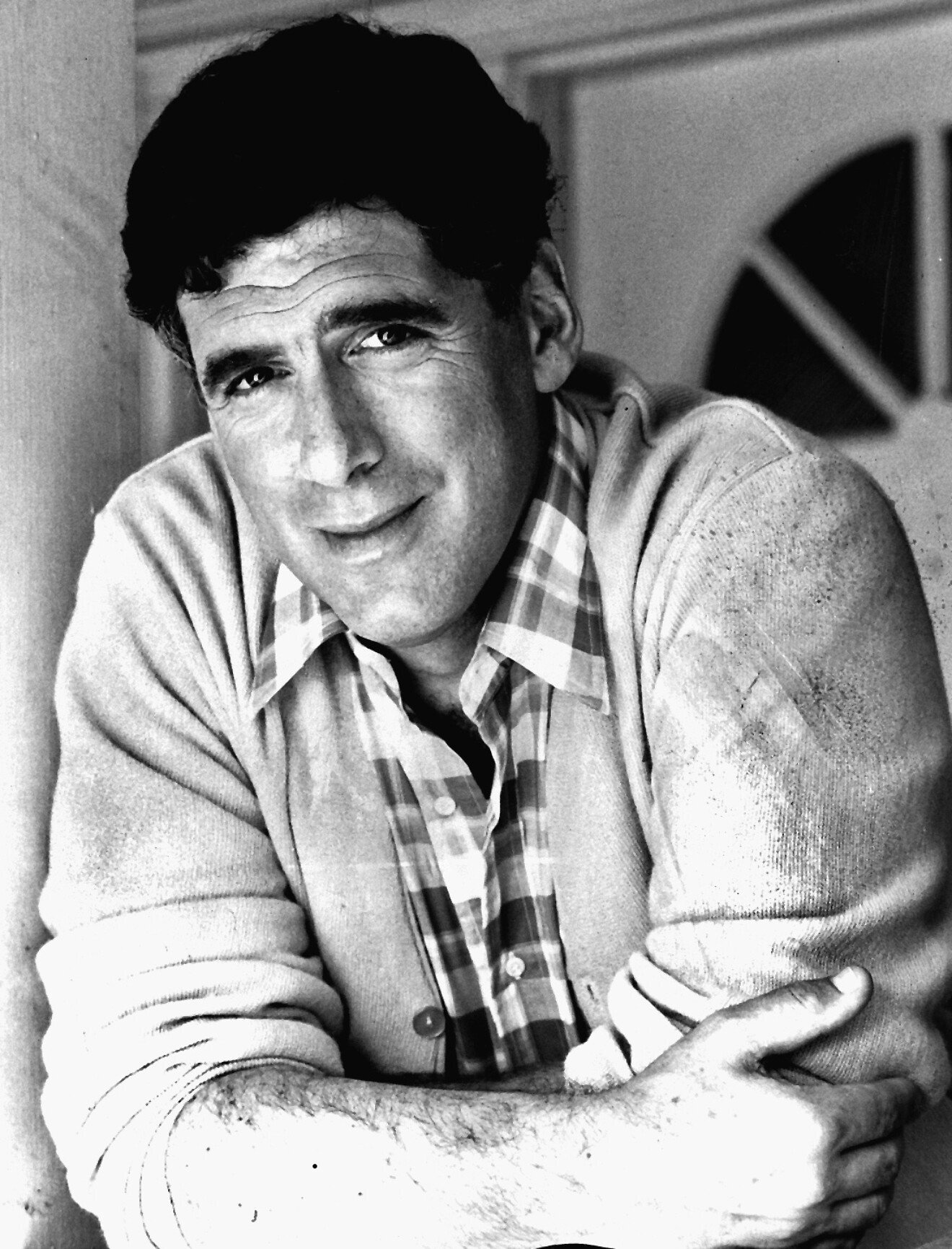

(JNS) — It’s difficult to imagine a face like Elliott Gould’s becoming a matinee idol today. It is angular and brooding, with eyes that have carried a weight beyond their years and a voice that teetered between irony and sincerity.

“Acting, for me, was always about truth,” he said in a recent conversation from his home in California. “And the truth is, I never fit in. That’s why I worked.”

Gould, 86, doesn’t so much act as inhabit a mood. He was never Hollywood’s golden boy—but that, in part, is what makes him unforgettable. Being Jewish has always been inseparable from his sense of self. “It’s not just a heritage,” he said. “It’s a moral responsibility.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In the early 1970s, at the height of New Hollywood’s golden age, Gould was the oddball heartthrob—a shaggy-haired rebel who seemed like he’d wandered in from another movie entirely.

In “M*A*S*H” (1970), he played Trapper John McIntyre with a mix of irreverent charm and moral disgust. In Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” (1973), his portrayal of Philip Marlowe felt like an anti-detective performance: loose, mumbled, weary, but somehow more real than Bogart tried to be. This wasn’t method acting; it was something more subversive. Something jazzier.

“I was just being me,” Gould said. “That was the only thing I ever knew how to do.”

‘It’s all Jewish to me’

Born Elliott I. Goldstein (the “I” is for Ishkowitz, from before Ellis Island) in 1938 in Brooklyn, N.Y., the actor came up the hard way: Broadway chorus lines, bit parts and a dogged belief that he could stand out by not blending in.

ADVERTISEMENT

His Jewishness wasn’t softened for the screen; it was centered. His neuroses weren’t concealed; they became his most powerful tools. Gould was one of the first major American actors to bring a kind of emotional improvisation to mainstream stardom—a willingness to unravel onscreen.

He has spoken at length about his Jewish upbringing, his early exposure to community and questioning, and how those values shaped both his artistry and his politics. “I don’t practice religion in a traditional way, but I’m a deeply Jewish person. My roots, my consciousness, my feeling for justice, for humanity—it’s all Jewish to me.”

‘Be careful with the world’

When it comes to the State of Israel, Gould is careful, considered and characteristically candid. A longtime supporter of Middle East peace efforts and dialogue, he has visited the country several times and even served as the president of the Haifa International Film Festival. He’s also been outspoken when it comes to Israeli policy, especially on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“I support Israel’s right to exist—absolutely,” he said. “But I also believe that real strength comes from empathy, from listening. We can’t claim to be a moral people and ignore the suffering of others. I think being Jewish means holding ourselves to a higher standard—not just surviving, but doing good.”

He added that he saw being Jewish—and being Israeli—as a responsibility to “be careful with the world.”

Gould’s comments have occasionally drawn criticism, but he’s never shied away from engaging. “I don’t have all the answers,” he said during a roundtable on Jewish identity in film. “But I know that being Jewish means asking the questions. If we lose that, we’ve lost the whole point.”

For a brief, brilliant period, he was among the biggest stars in the world. “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice” (1969), a sexually-charged satire on the California lifestyle, made him bankable. The films that followed made him iconic. But like many of his contemporaries—Peter Bogdanovich, Cybill Shepherd, even Robert Altman himself—Gould’s trajectory didn’t follow the Hollywood playbook. He chose odd roles, eschewed traditional stardom, and, by the 1980s, had largely faded from view.

“I made some decisions that weren’t popular,” he said. “But I never stopped working. I just stopped being in the tabloids.”

Yet Gould never truly disappeared. For decades now, he’s been a stealth presence in American pop culture: Ross and Monica’s dad on “Friends,” the slick Reuben Tishkoff in Soderbergh’s “Ocean’s Eleven” trilogy, and countless cameos that remind viewers just how singular a screen presence he remains. His portrayal of David “Legal” Siegel on the Netflix legal drama The Lincoln Lawyer brings heart and gravitas to the series—a moral anchor and emotional touchstone that holds the show steady.

There’s a kind of dignity in Gould’s endurance. He never rebranded, never reinvented himself to fit the moment. He aged on-screen the way we all hope to age: with a sense of humor, a bit of mystery and the self-awareness of someone who’s seen it all and survived with stories to tell.

Today, at 86, he remains active not just in film and television, but in life. He speaks often of spirituality, therapy and what it means to live authentically in a business that rewards facades.

He has been married three times—once to singer Barbra Streisand, with whom he had a son, actor Jason Gould; and twice to Jennifer Bogart, with whom he had two children, Molly and Samuel.

In a culture addicted to reinvention and comeback arcs, Elliott Gould is something else entirely: a man who stayed true to his own rhythm, even when the music changed. In doing so, he carved out a legacy that remains quietly influential, deeply human and unmistakably his own.