(JTA) — An exhibit at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan, “Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art,” examines the Nazis’ theft of masterworks from the collections of the Jews they persecuted and of others they merely exploited. Andrew Silow-Carroll, the New York Jewish Week’s editor in chief, and Ben Sales, a reporter for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, recently visited the exhibit and came away with different impressions. An edited version of their online conversation is below.

ANDREW SILOW-CARROLL: You and I both took in The Jewish Museum’s new exhibit on artworks looted by the Nazis, “Afterlives.” The critical response to the show has been mixed, and I think you and I disagree a bit about it. Let me start by saying that the show presents an unavoidable challenge for the viewer: Are we there to “enjoy” the works by Chagall, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Pissarro that grace the walls? Or is their recovery after the war a reminder of all the human lives lost? In learning more about “The Monuments Men” and other rescuers of European treasures, are we meant to honor the Allies who fought the Nazis and saved Western culture or lament all the ways the West failed to save actual human beings?

BEN SALES: Those were some of my central questions as well. “Afterlives” boiled down to a decent art exhibit featuring a range of well-regarded painters from the mid-19th to the early 20th century. But I can get a much better version of that eight blocks away at The Met.

The human question also occurred to me. But I will say this: If this exhibit is asking people to accept the premise that art is worth saving, that’s not an unreasonable request in and of itself. At the same time, it would have been nice to acknowledge that the Allies could have, and should have, devoted more energy to saving people than saving art.

This story is part of JTA’s coverage of New York through the New York Jewish Week. To read more stories like this, sign up for our daily New York newsletter here.

ANDY: Dara Horn makes a similar point in her new book, “People Love Dead Jews,” in her essay about the Holocaust rescuer Varian Fry: “Fry tried to save the culture of Europe and for that he should be remembered and praised. But no one tried to save the culture of Hasidism, for example…,” she writes.

ADVERTISEMENT

The exhibit’s strength, I felt, was in how its sheds light not just on the Nazis’ assault on Jewish bodies but on “Jewish” ideas. Many of the works on view were seized and condemned by Hitler as examples of “degenerate” art, which he viewed as a distinctly Jewish corruption of the noble ideals of classical painting, sculpture and music. (One of the paintings on display, “Battle on a Bridge,” the 17th-century French artist Claude Lorrain’s weirdly pastoral depiction of a famous Roman battle that established Christianity’s victory over paganism, was a favorite of Hitler’s.) The message may be indirect, but it lands: The Nazi program was a cultural battle as well as a military one, meant to “reclaim” Germany and Europe from its Jewish usurpers.

On display at the Jewish Museum is a photograph by Johannes Felbermeyer, “Movement of repatriated art,” c. 1945-49, showing Allied forces storing and processing recovered art at the Munich Central Collecting Point. (Johannes Felbermeyer Collection, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, via Jewish Museum)

BEN: In Fry’s defense, at least he was saving actual people: artists and writers like Marc Chagall, André Breton, André Masson and maybe 2,000 others. But I agree that this was one of the exhibit’s strong points. I also enjoyed the descriptions next to each piece of its provenance and journey. In fact, I may have spent more time reading those than I did actually looking at the art.

But I think visitors would have been better served had the exhibit doubled down on that. Instead of being an exhibit of paintings, it could have focused on Jewish collectors, the ideas that animated them, their relationships with artists, how their collections were looted, etc. — with a few representative works. There could have been a wall, for example, dedicated to the Degenerate Art exhibit of 1937, the works removed from museums by the Nazi government and displayed as the “art of decay.”

ANDY: What did you think of the treatment of the museum’s own efforts of rescue and recovery, before and after the war? On view are antique ceremonial objects sent to New York by communities and individuals for safekeeping ahead of the Nazi invasion of Poland and other countries. Institutions like the museum, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan made sure they were kept safe.

BEN: I can’t stop thinking of the row after row of Havdalah spice boxes and Torah scroll adornments sitting on shelves behind glass, each affixed with a little tag, each representing one family, or community, that will no longer celebrate Havdalah. In a way, the tags reminded me of Auschwitz tattoos, each cataloging destruction in its own way.

It’s a haunting image and an understated, powerful way of showing all we’ve lost.

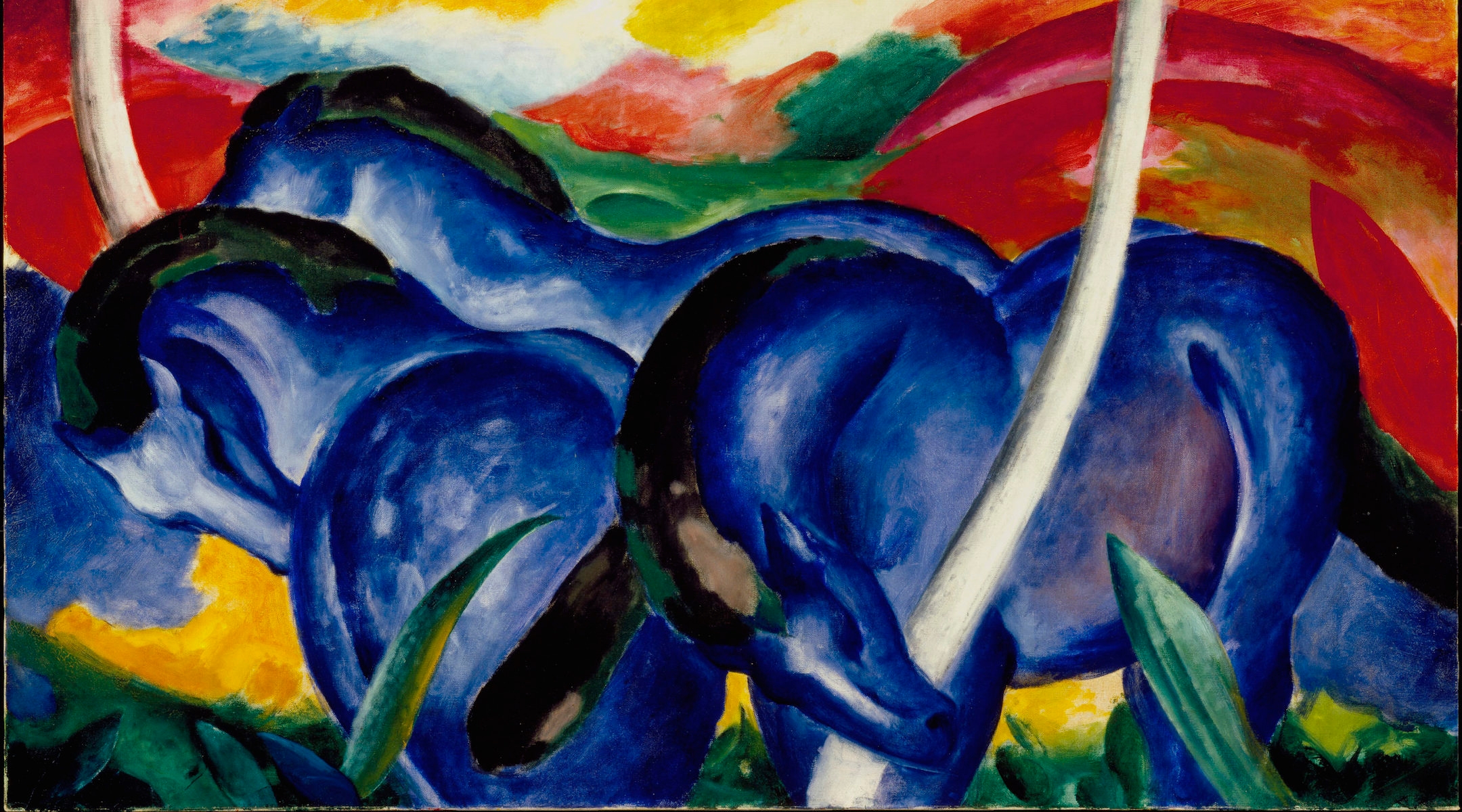

ANDY: And I was haunted by a small ledger on display that was kept by a political prisoner at Dachau, containing the names of 3,478 men, women and children, of whom only 11 would survive the camp. It comes at about the halfway point of the exhibit, which begins with a gorgeous painting by the German Franz Marc, “The Large Blue Horses,” and ends with a clip of the Nuremberg Trials. To me the message came through loud and clear: Between beauty and justice there is unimaginable destruction. “Afterlives” demands that you hold all three ideas in your head at once.

Work by Franz Marcus, whose 1911 painting “The Large Blue Horses” is in the Jewish Museum exhibit, was targeted by the Nazis as “degenerate.” (Walker Art Center via Jewish Museum)

BEN: But here’s my problem: The bulk of this exhibit was about art that has been restituted, and efforts of the Allies that did bear fruit. But we know, from abundant sources, that a lot of art was not restored to its original owners, which the exhibit notes but does not focus on. The fact that, 80 years after the Holocaust, there are still ongoing disputes about looted art means that this struggle is far from over. That’s been addressed in a variety of media — Malcolm Gladwell has a fantastic podcast episode about it, “Hedwig’s Lost van Gogh,” and there’s the Helen Mirren movie, “Woman in Gold.”

But the exhibit doesn’t spend enough time on the fact that a lot of art was stolen and never returned, even works that currently hang on the walls of prestigious museums. I was genuinely surprised and disappointed by that lack. And I couldn’t help but notice that one of the lenders to the exhibition is the Yale University Art Gallery, which, per Gladwell, itself possesses stolen art. It fought a successful court battle to keep a van Gogh that it purchased from the Soviet Union, which had stolen the painting in 1918.

My larger problem with that choice is actually the same problem I have with Holocaust movies: Way too many of them have a “happy” ending. It feels weird to even write this, but the Holocaust did not have a happy ending. It isn’t a story of success; it’s a story of failure. This exhibit, too, should have been a story of failure. It was not.

ANDY: I hear that. But I do think that is also the implicit challenge of the exhibit. There is, for example, the fascinating display of documents from Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, an organization founded by the historian Salo Baron and administered by the philosopher Hannah Arendt. JCR took custody of recovered Jewish cultural property and either restituted books and objects to their original owners or heirs or found them a new home. The exhibit includes correspondence from Arendt, discussing the fate of “heirless” or “orphaned” works whose original owners were either dead or could not be identified.

And to me, the dilemma and paradoxes were obvious and heartbreaking: JCR’s efforts are loving, ensuring the continuity of a culture Hitler tried to snuff out. But the losses they represent are overwhelming.

—

The post What NY’s Jewish Museum got right and wrong about looted art: An exchange appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.