On foreign policy, Jeb Bush navigates between brother and father

Published February 23, 2015

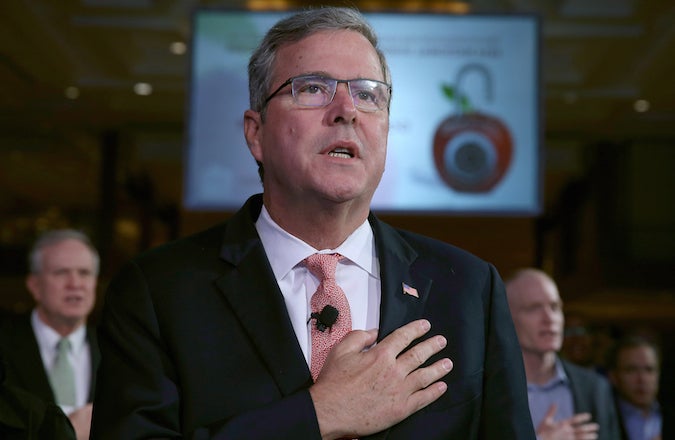

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush has surrounded himself with foreign policy advisers who have worked for his father and brother as he eyes a run for the presidency. (Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

ADVERTISEMENT

WASHINGTON (JTA) — As clearly as Jeb Bush has stated that he does not want his foreign policy chops assessed against that of his brother — or his father — his choice in advisers has only made things murkier.

Of 21 advisers to the former Florida governor and putative presidential candidate named last week, just two did not work for President George H.W. Bush from 1989 to 1993 or for George W. Bush from 2001 to 2009. And one of those, former Secretary of State George Schultz, was close to Bush’s father when they both were in the Reagan Cabinet.

And because the Georges Bush, father and son, have such disparate records on the Middle East, pro-Israel groups already are picking through the choices and trying to assess which way Jeb Bush leans.

“His father’s [administration] was known as cooler to Israel, his brother’s as warmer,” said Dov Zakheim, who worked in the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations.

Among the advisers are James Baker, the elder Bush’s secretary of state who is known to have said “F*** the Jews” when another Cabinet member suggested that the Jewish vote should factor into a consideration of Israel policy. Baker also openly taunted then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir with the White House phone number, saying Shamir should call when the Israeli leader was ready to talk peace.

ADVERTISEMENT

Baker’s protege under the elder Bush, Robert Zoellick, also is an adviser and, like Baker, is a leading thinker in foreign policy’s “realist” school — less likely than neoconservatives to push for transformation overseas.

Among George W. Bush presidency veterans are John Hannah, an adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney and part of a cohort within that administration considered the closest to Israel, and Paul Wolfowitz, like Hannah a prominent neoconservative thinker and, as deputy defense secretary, an architect of the Iraq War.

Also advising Jeb Bush are two of his brother’s top Jewish Cabinet officials: Michael Chertoff, the former Homeland Security secretary, and Michael Mukasey, the ex-attorney general.

Bush’s frustration with the comparisons was evident last week at his signature foreign policy rollout at the Chicago Council on Foreign Affairs.

“For the record, I love my brother, I love my dad, I love my mother as well, hope that’s OK, and I admire their service to the nation,” he said. “But I am my own man.”

Bush also devoted a significant chunk of his speech to praising Israel and criticizing President Barack Obama for his foreign policy, particularly having to do with the Iran nuclear talks now underway.

“Nuclear weapons in Iran was once a unifying issue within American foreign policy,” said Bush, who also noted that he had visited Israel five times. “Leaders of both parties agreed to it. When he launched his negotiations, President Obama said that that was the goal — to stop Iran’s nuclear program. Now we are told that the goal has changed. The point of these negotiations is not to solve the problem, it is to manage it.”

Republicans and Israel’s government have criticized the emerging deal for allowing Iran to maintain limited uranium enrichment, which they say leaves Iran as a threshold nuclear weapons state. Obama administration officials say there are other guarantees that will keep Iran from acquiring a weapon.

As much as Bush focused his speech on Obama as the template he wanted for favorable comparison, questions about whether he prefers his father’s policies or his brother’s are not going away.

Any Republican candidate for president inevitably would draw on experience garnered during the last two GOP presidencies, but Mitt Romney and John McCain, the 2012 and 2008 nominees, respectively, drew plenty of foreign policy advisers from congressional staffers as well as the punditocracy. The one Jeb Bush adviser not aligned with either president is Lincoln Diaz Balart, a former Cuban-American congressman from Florida. Of the 21 advisers, 13 worked for George W. Bush, two for his father and four for both men.

Regarding Israel, the starkest contrast between the two presidents Bush has to do with Israel’s claims to the West Bank. The elder Bush clashed publicly with Israel’s government over settlement expansion. Meanwhile, in a 2004 letter to then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, the younger Bush recognized some settlement enclaves as “realities on the ground” — the first U.S. recognition of any Israeli claim in the West Bank. However, behind closed doors he continued to press for an end to settlement expansion.

The broader contrast and the one likelier to preoccupy Jeb Bush has to do with Iraq. The elder Bush waited until building as broad a coalition as possible before engaging in a limited war with Iraq in 1991 after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq’s leader, Saddam Hussein. The U.S.-led victory helped reinforce American ascendancy in the post-Cold War period.

The younger Bush led a much smaller coalition invading Saddam’s Iraq in 2003, seeking broader outcomes, including the installation of a pro-Western government. Instead the invasion led to turmoil that still persists.

Whose path would Jeb Bush choose? His speech in Chicago suggested that he was influenced by both outlooks.

Like his brother, he appeared averse to engaging publicly in spats with allies like Israel. Bush was appalled at the tit-for-tat vituperation that has recently characterized the relationship between the Netanyahu and Obama governments. Obama’s administration, he said, “has lobbed insults at Prime Minister [Benjamin] Netanyahu with incredible regularity.”

Also, like his brother, he tended to cast alliances not simply as a matter of shared interests but of emotional investment.

In his five visits to Israel, Bush said, “I have had the incredible joy of seeing the spirit of Israel.” He said signing a Florida trade agreement with Israel was a highlight of his governorship.

Yet there are signs, too, that Bush harbors the caution that characterized his father’s foreign policy.

“If we want to build confidence and trust in the American position, we have to listen,” he said in what was seen by some as an allusion to his brother’s reluctance to take counsel from American allies. “The president needs to set a strategy and be clear about it, not overcommit or overpromise, but always strive to deliver.”

A more direct jab at his brother came in response to a question about the value of advancing democracy through elections — something George W. Bush was criticized for emphasizing at the expense of caution and U.S. interests.

“This is a problem of presidents past as well, in all honesty, ‘If you have an election, you are a democracy,’” he said. “Hamas had an election, Hezbollah competes. These groups are not supportive of democracy; they use the election process to take away freedom from people.”

Notably, the elections that raised Hamas and Hezbollah to influence occurred on his brother’s watch, and in the Palestinian case, at his insistence.

![]()