Leonard Cohen, my father and me

Published November 11, 2016

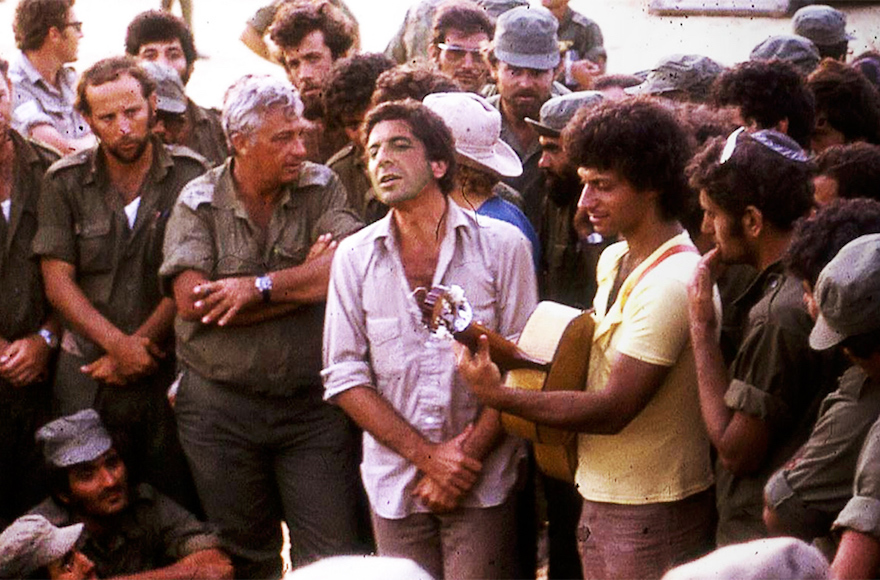

Leonard Cohen, center, performing with Matti Caspi, on guitar, for Ariel Sharon, with arms crossed, and other Israeli troops in the Sinai in 1973. (Courtesy of Maariv)

Using his M-16 assault rifle as a pillow, my father awoke abruptly from a dreamless sleep by the pleading voice of a young woman outside his tent in the Sinai.

ADVERTISEMENT

The woman, a uniformed volunteer, was urging reservists like him to forego shuteye to hear a musician whose name she did not know, but who had come from far away to perform for Israeli troops on the southern front of Israel’s traumatic 1973 war with Egypt and Syria.

Stumbling out of the khaki tent, my father and 12 other soldiers encountered Leonard Cohen, the eminent Jewish Canadian poet-singer whose death, at age 82, was reported Thursday, prompting passionate eulogies from fans all over the world, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Reuven Rivlin.

Cohen’s visit to the Sinai Desert, during which he wrote his haunting song “Lover Come Back to Me,” was the beginning of my family’s bigenerational love affair with his irreverent yet spiritual writing. Cohen’s benign sobriety has shaped me as very few other writers have.

In the best-known photograph from his tour of the front line, spending at least a week performing at gathering points and bases, a singing Cohen stands next to an attentive Ariel Sharon, the Israeli general and future prime minister who clinched victory from the jaws of defeat during that war. The Israeli virtuoso composer Matti Caspi is accompanying Cohen on guitar as dozens of soldiers huddle all around them — some wearing expressions that suggest deep reflection.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the concert attended by my father, a noncommissioned communications officer in charge of connecting Sharon to higher-ups whose orders Sharon was notorious for ignoring, was somewhat less photogenic.

“So a dozen of us who agreed to wake up saw this sweaty Jew wearing dusty fatigues standing with a guitar in the sun,” my father recalled Friday upon learning of Cohen’s passing. “I’m pretty sure the other guys had no idea who he was and I doubt that that changed thanks to the concert, which, honestly, was kind of heart-wrenching.”

When they were finally dismissed, my father’s brothers-in-arms complained about the concert, which they found dull. They had hoped for a show by the ha-Gashash ha-Khiver, a famous Israeli comedy ensemble whose Hebrew name means “The Pale Scout.”

It was an awkward situation for Cohen, whom Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on Friday called a “warmhearted Jew” in recalling Cohen’s impulsive decision to come to the front lines — something the prime minister also experienced firsthand. (At the time, Cohen was living in Greece with his girlfriend, Suzanne Verdal, who served as the inspiration for one of his best-known songs, “Suzanne.”)

But my father was bowled over. He recognized Cohen instantly — his songs, he said, had hit him like a thunderbolt when he first heard one of his records some years earlier.

“His lyrics were poetry, not pop, they were deeply sober but almost never veered into neither the outright sarcasm nor the activism that one finds in Bob Dylan’s sung poetry, for example,” said my father, who has an acute allergy to anything that reminds him of the politicized art he experienced growing up in communist Poland.

Leonard Cohen performing at a concert in Ramat Gan, Israel, Sept. 24, 2009. (Marko/Flash90)

As for me, I was a reflective and slightly morose 14-year-old when my father introduced me to the music of Leonard Cohen. I was mesmerized by his trademark levity, with which he explored deep and sometimes dark emotions. Like my father before me, I had never heard anything quite like it.

I was deeply influenced by the self-doubting words and nasal voice of this strange bird on a wire, forever searching for a perch from which to observe the human soul with love but without illusions.

His way of looking at the human psyche, which I hungrily analyzed in his songs and in his two novels, shaped in no small part my own way of looking at the world.

In “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” his simple and intimate descriptions of a lover informed my first notions of romantic love with lyrics like “Your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm.”

In “Everybody Knows” he shook my naive perceptions about race relations and the balance of power — “Old Black Joe’s still pickin’ cotton for your ribbons and bows.” He did it again in “Democracy” — “the homicidal bitchin’ that goes down in every kitchen to determine who will serve and who will eat.”

And he even taught me to laugh at a taboo in “The Captain” (“Complain, complain, that’s all you’ve done ever since we lost. If it’s not the Crucifixion, then it’s the Holocaust.”)

Which is why it broke my heart to skip, for ideological reasons, his concert in Israel in 2009. Under pressure from promoters of the Boycott, Sanctions and Divestment movement not to perform in the Jewish state, Cohen partially buckled by saying he’d also perform in Ramallah as well as the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan.

When that proved impractical, he agreed to donate the concert’s proceeds to organizations whose supporters refer to as peace groups.

And while I see nothing wrong with either decision, I did not wish to reward his partial surrender to individuals and organizations that as I see it abuse and leverage artists to promote political ends.

It didn’t help that one of the organizations that received some of the proceeds was a group of bereaved Palestinian and Israeli parents who had lost children to the conflict. While I recognize the universality of grief, I found that the rhetoric of this particular parents’ circle risked creating a moral equivalence between terrorists and their killers.

I had expected more from Cohen, whom I fortunately got to see, after all, when he toured Europe in 2012.

But my father took a different view. The discussions we had on this point became yet another case in which Cohen, from his tower of song, informed both my outlook and my relationship with my father, who is by far my best debate adversary.

“I can see why a man like Cohen, who also practiced Buddhism, decided to try for and promote compromise instead of ignoring dissent,” my father told me.

I have changed my views on the 2009 actions of Cohen, who is the closest thing to a rabbi that I’ve ever had. I now see them as part of his legacy, which has taught me to adhere to my own convictions — as he did during the Yom Kippur War — without, out of insecurity, placing them over the convictions of others.

While Cohen’s music will stay with me forever, I’m ready to let him go. It’s a good way to say goodbye.