Is Bernie Sanders the Democrats’ new foreign policy maven?

Published September 26, 2017

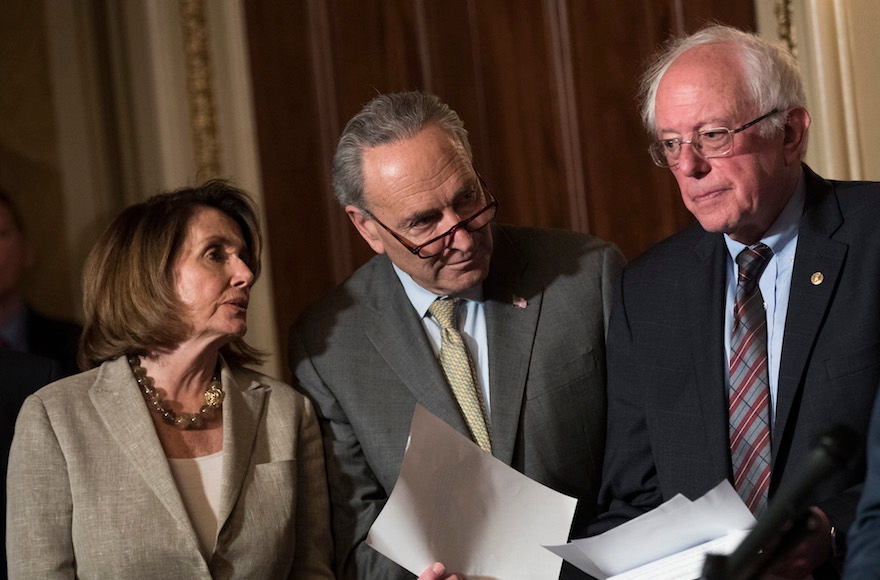

From left to right: House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer and Sen. Bernie Sanders at a Capitol Hill news conference, May 25, 2017. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Bernie Sanders, a senator from Vermont, is still an Independent, but he’s no longer an outsider.

ADVERTISEMENT

That became clear this month when some Democratic establishment stalwarts in the Senate signed on to his “Medicare-for-All” bill, which would establish a single-payer system for health care.

Hillary Clinton is on a book tour and Barack Obama is mostly silent, so for Democrats, Sanders for now is the party’s “It” Guy battling against President Donald Trump.

Last week, the first Jewish presidential candidate to win nominating contests in a major party took his newfound status and ventured into foreign policy, delivering a speech Sept. 21 at Westminster College in Fulton, Mo. It’s the same place where Winston Churchill laid out his vision for the West in the postwar period — a robust antagonism toward communism largely emulated by Western democracies in subsequent decades.

Would Sanders have the same impact? To see where the party may be heading, the pro-Israel community and Democratic insiders closely studied the speech, as well as an expansive interview on Middle East policy published the next day in The Intercept in which he repeated tough criticisms of decades of U.S. policy.

The tentative conclusion: The speech was mostly rehash.

It decried the 2003 Iraq War that many Democrats see as the precipitator of the turmoil now besetting the world, but also rejected Trump’s isolationism. It didn’t break new ground. Sanders listed a litany of failed postwar U.S. military interventions — in Latin America, Southeast Asia and the Middle East — while noting that the signature success was the Marshall Plan, which used diplomacy and economic assistance to help build a peaceful Europe. He held up the 2015 Iran nuclear deal reviled by Trump and Israel’s prime minister as a model for engagement.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The Iran nuclear deal advanced the security of the U.S. and its partners, and it did this at a cost of no blood and zero treasure,” he said of the agreement, which swaps sanctions relief for a rollback of Iran’s nuclear program. “What the Obama administration and our European allies were able to do was to get an agreement that froze and dismantled large parts of that nuclear program, put it under the most intensive inspections regime in history, and removed the prospect of an Iranian nuclear weapon from the list of global threats.”

Tamara Cofman Wittes, a top Middle East official in Obama’s first term, said the speech was nowhere near the radical departure that Sanders’ single-payer bill represented — attaching the Democratic Party to a Canadian- and European-style system it has resisted embracing for decades.

“As I read the speech, the substance of it was Barack Obama’s foreign policy,” Wittes, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, said in an interview. “I didn’t hear anything that was a big departure.”

She was amazed that Sanders did not address a topic that would be a natural for an economic populist — trade.

“Does he like it or not like it, how does it fit into the international liberal order?” she asked.

For all the pomp that preceded the speech — Sanders’ staff and acolytes did not miss a chance to note the Churchill connection — its tone was hesitant and the parameters Sanders said he was setting down were squishy and vague.

“As the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth, we have got to help lead the struggle to defend and expand a rules-based international order in which law, not might, makes right,” he said. “We must offer people a vision that one day, maybe not in our lifetimes, but one day in the future, human beings on this planet will live in a world where international conflicts will be resolved peacefully, not by mass murder.”

Sanders supporters in the party acknowledged that he was not so much breaking new ground as staking out the traditional Democratic foreign policy values — diplomatic engagement with use of the military as a last resort — in a public arena that seems preoccupied with internecine Republican warfare.

“If you turn on the Sunday talk shows, you have neoconservatives and isolationists,” said Ilya Sheyman, the executive director of MoveOn.Org, the grassroots organization that backed Sanders in his losing primary battle against Clinton. “Barack Obama was elected on a platform to pursue diplomacy,” but that posture has receded as Democrats are preoccupied with winning the next elections and with domestic issues.

“When you have the most popular politician in America making the case for diplomacy first, others will pay attention,” Sheyman said, referring to recent polls ranking active politicians.

James Zogby, the Arab American Institute president who was a Sanders delegate to the Democrats’ platform drafting committee last year ago, said the speech was an “opening shot.”

“He’s still shaping thoughts; these are issues he will expand on,” Zogby said. “Democrats have been notoriously weak on foreign policy.”

Unlike the single-player proposal, the speech did not resonate much throughout the Democratic establishment.

Typically strong Jewish voices in the Senate like Charles Schumer of New York, the minority leader, and Ben Cardin of Maryland, the top Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee, declined comment when asked by JTA for remarks on the address.

One establishment Democrat, Chris Murphy of Connecticut, welcomed it.

“Glad that my friend Senator Sanders is joining the fight for a progressive foreign policy,” he tweeted.

In the Intercept interview published the day after the speech, Sanders grudgingly addressed an issue he omitted at Westminster: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The senator said, as he had in the past, that he favors less U.S. defense assistance to Israel, and that the United States should be more evenhanded in dealing with the issue.

But The Intercept’s Mehdi Hassan, a tough critic of Israel who favors Palestinian rights, seemed intent on getting Sanders to say that the United States is “complicit in Israel’s occupation,” and that military aid and arms sales were perhaps the main obstacles to resolving the conflict.

Sanders wouldn’t go that far.

“Certainly the United States is complicit, but it’s not to say … that Israel is the only party at fault,” Sander said. “In terms of Israeli-Palestinian relations, the United States has got to play a much more evenhanded role. Clearly that is not the case right now.”

Hassan pressed Sanders on reducing aid to Israel.

“The U.S. funding plays a very important role, and I would love to see people in the Middle East sit down with the United States government and figure out how U.S. aid can bring people together, not just result in an arms war in that area,” Sanders said. “So I think there is extraordinary potential for the United States to help the Palestinian people rebuild Gaza and other areas. At the same time demand that Israel, in their own interests in a way, work with other countries on environmental issues.”

Only then, Hassan wrote, did Sanders answer the question about reducing aid.

“So the answer is yes,” the senator said.

Despite the obvious reluctance by Sanders, the answer would alarm pro-Israel centrists in the party, said Robert Wexler, a former Florida congressman who campaigned for Clinton.

“Certainly Senator Sanders has influence at the grassroots level, and that’s why I respect his views so much, and that’s why he should be more judicious in the presentation of his views,” Wexler said.

Still, he was not concerned Sanders had much traction.

“Let’s be real, Chuck Schumer is the Democratic leader in the U.S. Senate,” he said, noting Schumer’s firm footing in the centrist pro-Israel camp.

More puzzling for Wexler was Sanders’ decision to deliver a key foreign policy speech on Rosh Hashanah, when many Jewish Democrats were unable to watch and listen in real time.

“I wish that Senator Sanders would make as great an effort to understand the legitimate concerns of the American Jewish community as he does with other communities,” Wexler said of a community that votes overwhelmingly Democratic and that contributes much to the party in terms of donations, volunteering and personnel. “Until he does that, I don’t think he’s eligible to lead the Democratic Party on these issues.”