In Alabama’s Senate race, Jews have become an issue. It’s not a first for the South.

Published December 12, 2017

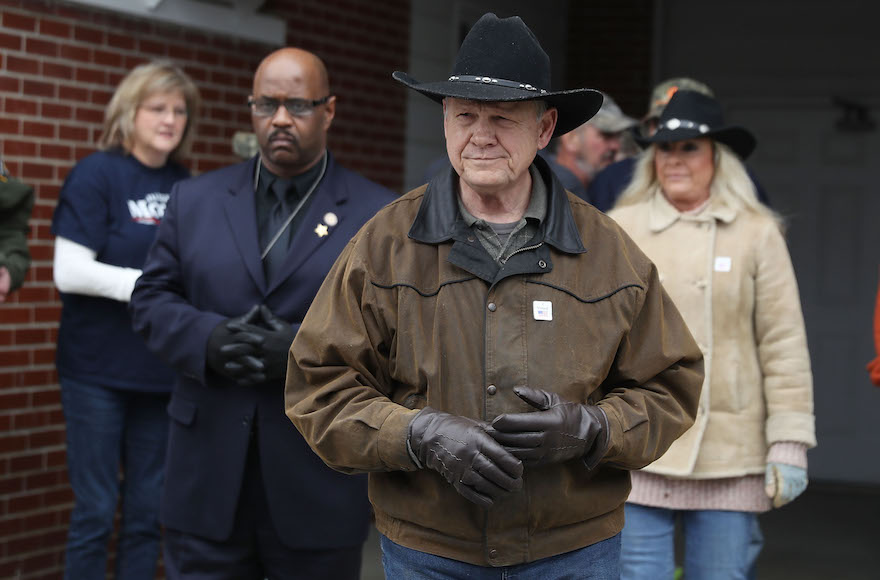

Senate candidate Roy Moore seen after casting his vote in Gallant, Ala., Dec. 12, 2017. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Jews have come up multiple times in the Senate election roiling Alabama, a state with few of them.

ADVERTISEMENT

Some mentions have been friendly and some, well, less so.

Among the friendly: The enthusiastic reception for President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital at a rally last week in Pensacola, Florida, that was essentially a campaign event for Roy Moore, the Republican candidate.

“Now I don’t know about you, but when I heard about Jerusalem — where the King of Kings, where our soon coming King is coming back to Jerusalem, it is because President Trump declared Jerusalem to be [the] capital of Israel,” Florida State Sen. Douglas Braxson said at the rally, which was packed with people who had traveled from neighboring Alabama to hear Trump endorse their candidate.

Then there were the signals from Moore and his campaign that to some Jews sounded like dog whistles, and in line with other recent instances when anti-Semitic inflections appeared in Southern elections.

Moore in an interview last week suggested that the billionaire Jewish philanthropist George Soros was going to hell. Soros is a Hungarian-born Holocaust survivor who funds liberal causes here and abroad.

“He is pushing an agenda, and his agenda is sexual in nature, his agenda is liberal and not what Americans need,” Moore said.

The religious imagery as well as the conspiracy, sex and “un-American” talk alarmed some Jewish observers.

“Moore is playing on well-known anti-Semitic tropes in which Jews are cast as outsiders using their money for evil intent,” said Rabbi Jack Moline, the president of the Interfaith Alliance who formerly was active in Democratic politics. “These comments have no place in public discourse.”

ADVERTISEMENT

And then there was Kayla Moore, the candidate’s wife, who apparently took offense with those who took offense with her husband’s remarks — and probably made things worse.

“One of our attorneys is a Jew,” she said at Moore’s final rally Monday evening, in Midland City, Alabama.

“There are really no words,” Jonathan Greenblatt, the Anti-Defamation League CEO, said on Twitter, reacting to Kayla Moore, although he found a word a few tweets later: “anti-Semitic.”

There really are no words. None.

— Jonathan Greenblatt (@JGreenblattADL) December 12, 2017

.@NPRinskeep on @MorningEdition points out how #SteveBannon went down to #AlabamaSenateRace telling rally that no one can tell ppl of #Alabama how to vote, then proceeded to tell them how to vote. Unsure if that was before or after Roy Moore’s wife made anti-Semitic comment

— Jonathan Greenblatt (@JGreenblattADL) December 12, 2017

Moore, a former judge beset by allegations that in his 30s he pursued teenage girls and in two cases assaulted them, is in a surprisingly tight race with Doug Jones, a former prosecutor. Moore denies the allegations.

Alabama has fewer than 10,000 Jews in a state of 5 million people, according to a 2013 estimate in the Jewish Virtual Library. Why are Jews on the Alabama agenda in Tuesday’s special election when they constitute so little of the population?

Josh Parshall, the director of the history department at the Institute of Southern Jewish Life, described three postures toward Jews among non-Jewish Southerners: admiration for Israel and Israelis among Christian evangelicals; affection that Southerners feel for their neighbors, Jewish or otherwise; and the “othering” of a people damned in some Christian teachings for killing Jesus.

“There has been ambivalence, the image of the Jews as the people who killed Christ,” Parshall said. “But there’s a strong strand of Christian philo-Semitism in the South as well as Christian Zionism which has played and continues to play a significant role. And in small towns, when Jewish people would found a synagogue, they would get contributions from local churches, local officials would be involved in laying cornerstones.”

Parshall said that anti-Semitism was not prevalent in the South and was not comparable to the region’s history of its treatment of blacks, from slavery through segregation and beyond. Southern Jews were often embedded in the structures advancing the disenfranchisement of blacks and therefore less likely to be subject to white Christian hostility.

“The acceptance of Jews has historically been contingent on their involvement in systems of segregation and disenfranchisement,” he said.

It is when Jews from outside the South have figured in Southern controversies — most prominently when activists from the North joined civil rights movement — that the othering tends to manifest, Parshall said. (Moore in his attack on Soros was reacting to a report that wrongly insinuated the billionaire was funding an effort to register local felons to vote.)

“At times, as in anywhere else in the country, Jewishness can be used as a tool to make someone seem as an alien and raise questions about their intentions,” he said.

Another factor may be the very low number of Jews outside the Atlanta area, said Kyle Kondik, who analyzes elections at the University of Virginia Center for Politics.

“In the South where there are very few Jews, in certain circles they would be seen as the ‘other,’” he said.

Rep. Steve Cohen, D-Tenn., said Moore was dog whistling to those who have little contact with Jews.

“The rural areas are not aware of and not sensitive to the Jewish issue,” said Cohen, who noted that his Memphis district and a neighboring one were both represented by Jews. (Rep. David Kustoff, R-Tenn., is the other congressman.)

“We’ve overcome anti-Semitism in the urban areas,” said Cohen, who faced anti-Semitic invective in a 2008 primary but went on to an overwhelming victory.

Cohen blamed Trump for drawing out anti-Semitism and other bigotries with rhetoric that at times has targeted minorities and shown deference to white supremacists.

“White supremacists have felt the president’s encouragement,” he said.

Yet the Alabama race is not the first one in recent history that a candidate’s Jewishness or alleged Jewish ties has been an issue in the South. Many instances predate Trump’s ascent.

* A 1978 election in South Carolina for an open congressional seat pitted Carroll Campbell, a Republican, against Max Heller, a Democrat who was a former mayor of Greenville and who had fled Nazi Germany. Lee Atwater, a hard-hitting campaign adviser to Campbell, ran a telephone poll asking respondents: “Would you vote for a Jew who did not believe in the Lord Jesus Christ?” Campbell won.

* In the 1996 U.S. Senate election in Kansas, some voters got a recorded call saying “We think it’s important for people to know that Jill Docking is Jewish. Please vote for Sam Brownback.” Brownback, a Republican, won — and became known as one of Israel’s fiercest champions in the Senate.

* Joe Straus, the Republican speaker of the Texas House, faced a challenge in 2010 from Republican activists who wanted a “true Christian conservative” in the job. Most of the party repudiated the attacks as bigoted and backed Straus, who is Jewish.

* Sen. George Allen, R-Va., running for re-election in 2006, fiercely denied a report that his mother was Jewish, insinuating that a reporter’s question to that effect was a slur. It turned out to be true and years later, speaking to a Jewish group, Allen said his denial cost him the election — and led him to reconnect with his Jewish roots.

* In 2013, John Whitbeck, a senior GOP official in Virginia, had to fill time at a rally for Ken Cucinelli, the Republican candidate for governor, because Cucinelli was running late. Whitbeck told an anti-Semitic joke about a rabbi, the pope and the Last Supper. (Cucinelli lost. Whitbeck, who apologized, remains active in state politics.)