Dutch survivor’s diary called an Anne Frank story with a ‘happy’ ending

Published October 11, 2016

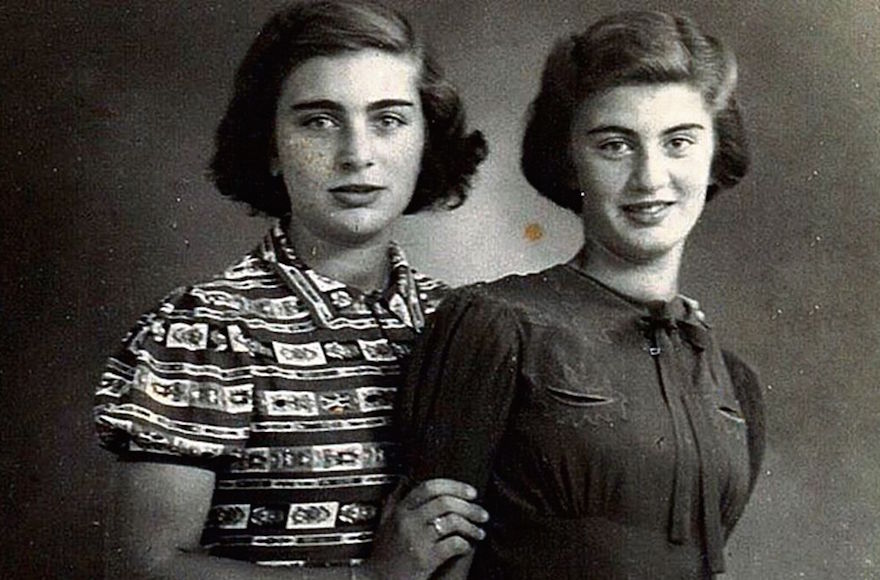

Carry Ulreich, right, and her older sister, Rachel, in a photograph taken during their time in hiding in Rotterdam during the Nazi occupation. (Boekencentrum/Mozaïek)

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — A Holocaust survivor dubbed “Rotterdam’s Anne Frank” in her native Netherlands published her wartime diary, which she wrote while hiding in the bombed-out city.

ADVERTISEMENT

“At Night I Dream of Peace,” the Dutch-language diary of 89-year-old Carry Ulreich, hit bookstores in the Netherlands last week. The book generated strong interest from the national media, which likened and contrasted Ulreich’s story with that of Frank, the murdered Jewish teenager from Amsterdam whose diaries in hiding were made into one of the world’s best-read books about the Holocaust.

Ulreich, who immigrated to Israel in the years after World War II, was 2 1/2 years older than Frank when the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1940 and sent many of the country’s 140,000 Jews into hiding. Unlike Frank, whose writings have been described as offering a universalist worldview, Ulreich displays a distinctly Jewish one, describing her deep emotional connection to Jewish prayer and traditions.

Whereas Frank and many of her relatives were among the 104,000 Dutch Jews murdered in the genocide, Ulreich survived to have three children, 20 grandchildren and over 60 great-grandchildren. She took her wartime diary, spread over several yellowing notebooks, to Israel but reread it only two years ago, deciding to publish. In an interview with the Dutch newspaper Trouw, she described her story as “like Anne Frank’s, but with a happy end.”

The book, in which Ulreich documented her family’s battle to survive as the world around them became increasingly dangerous, is among a handful of detailed testimonies of life in hiding in Rotterdam, which unlike most Dutch cities was largely destroyed in massive aerial bombardments both by the Germans and later the Allied forces.

ADVERTISEMENT

It affords a rare account of the sometimes awkward encounter between the Ulreichs, a Zionistic and traditionalist family from Eastern Europe whose members were proud of their Jewish heritage, and their deeply religious Catholic saviors, the Zijlmans family.

Whereas the Franks, a family of secular and cosmopolitan Jews from Germany, lived apart from the people who hid them, the Ulreichs lived with the Zijlmans in conditions that required considerable sacrifice on the part of the hosts and led to some friction as the two households interacted.

The Zijlmans couple, who were recognized by Israel as Righteous Among the Nations in 1977 for risking their lives to save the Ulreichs, gave their bedroom to the Ulreichs and moved into a small room where potatoes were stored. They also severed their social contacts to avoid detection as their guests lived in fear.

“We are simply terrified that they will report us to the Waffen-SS for neighborhood disturbance,” Ulreich wrote of the neighbors. “Then they will come with their truck, and we’ll have to go to Westerbork and then to Poland and after that … death?”

Westerbork was a Nazi transit camp in Holland’s northeast.

Ulreich also recalls hearing a chazan, or cantor, offer a prayer for Holocaust victims on a British radio transmission, which she said made the Jews cry and feel “connected with him by heart.” But she complains over the airing of the prayer on Shabbat, when Jews are not supposed to turn on the radio.

“The Christians try to support us, but they simply don’t understand these things,” she wrote.

“Carry shows, next to the enormous gratitude for the hospitality, the discomfort of two different families who suddenly have to live together,” wrote Bart Wallet, the editor of the diary and expert on Dutch Jewry with the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. “The tension and complete dependence are almost tangible for the reader.”

The diary also describes theological discussions between the families.

“This book reveals a lot of information about a, until now, highly undiscussed topic: the religious life in hiding,” Wallet wrote. “It shows how the Jews struggled to eat kosher and how they still tried to celebrate their holy days.”