Buzzed by planes, sporting toupees: The ups and downs for Jews in the security services

Published February 18, 2015

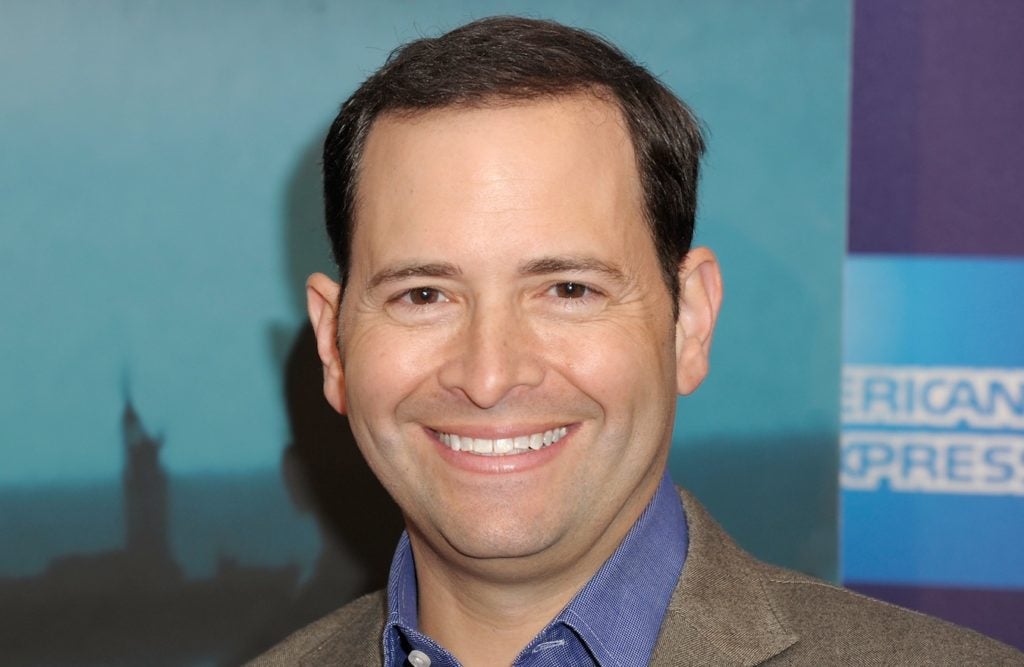

Adam Ciralsky, seen here at the 2013 world premiere of his film ‘The Project’ in New York, was a CIA lawyer who sued the agency after his security clearance was revoked. (Dave Kotinsky/Getty Images for Tribeca Film Festival)

ADVERTISEMENT

WASHINGTON (JTA) — David Cohen, who was named deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency earlier this month, is not the first Jewish-American to reach the agency’s upper ranks. John Deutch headed the agency for a short period in the mid-1990s.

But Jewish community professionals familiar with the American security community say his ascension is a sign that the past scrutiny of Jewish intelligence staffers is abating.

The best-known case is that of Jonathan Pollard, the former Navy analyst who was sentenced to life in 1987 for spying for Israel. But other lesser known cases show how the American government has been overzealous at times in its scrutiny of Jewish staffers.

Adam Ciralsky, a CIA lawyer who had his security clearance revoked in 1999, sued the agency. In depositions, Ciralsky discovered that he was under suspicion in part because his father had purchased Israel Bonds and because of a distant relation to Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, who by then had been dead for decades.

In documents first reported in 2012 by the Daily Beast, it was revealed that a polygraph test administrator had referred to Ciralsky as a “little Jew bastard.” In other documents he was referred to as a “rich Jewish employee with a wealthy daddy.” Ciralsky dropped the case in 2012.

ADVERTISEMENT

Now a journalist who writes and produces films about the military and the Middle East, Ciralsky would not comment for this article. But Neal Sher, a lawyer and former director of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee who represented Ciralsky at the outset of his case, said the CIA’s attitude betrayed a fundamental misconception of how American Jews relate to Israel, with some investigators seeing routine pro-Israel acts like buying bonds as inherently suspect.

“It exposed in certain quarters in the intelligence community and in law enforcement [that] there is this deeply seated mistrust of American Jews,” Sher said.

In some cases, the very skills attracting the government to a staffer were later used against him.

In 2008, the Pentagon inspector general found that David Tenenbaum, a Jewishly observant engineer whose Hebrew led the army to assign him to work with Israeli counterparts on protecting armored vehicles, was the target of an investigation sparked by suspicions based on his faith and ethnic background.

Tenenbaum told the Washington Post then that the very trips to Israel he undertook for the U.S. Army led to the suspicions.

“The same reason they hired me, they suspected me,” he said.

Tenenbaum, who is writing a book about his case, declined an interview, but his website describes the 1997 FBI raid on his home.

“The investigation began with a raid of the Tenenbaums’ home during Shabbat and resulted in the confiscation of the children’s music and coloring books,” it says. “The entire Tenenbaum family was placed under 24-hour surveillance, and Dr. David Tenenbaum made the headlines of the local newspapers where he was labeled a spy.”

Mark Mallah, a former FBI special agent, became an outspoken opponent of polygraphs after an anomaly on a test in 1995 led to accusations, never borne out, that he had unauthorized contact with foreign officials. That triggered an FBI raid of his home and agents interviewing his friends and family.

“Following the search and for about two months afterward, I was under surveillance twenty four hours a day, seven days a week,” he wrote for an anti-polygraph website. “For at least a week during that time, a small airplane circled above our home every morning, then buzzed above me wherever I went.”

Mallah quit the bureau in 1996 after being cleared. No one ever told him which foreign officials he was suspected of contacting.

In an email interview, Mallah said he believes the main driver of the investigation was the FBI’s refusal at the time to acknowledge the flaws in polygraph tests. But he believes there was a Jewish dimension as well.

“My being Jewish provided additional impetus and focus to the investigation,” Mallah said. “I believe that in the wake of the Pollard situation, they probably believed, or at least suspected, that there were other Pollards out there and they did not want to get burned twice. So better to trample on any notions of due process, fairness, even objectivity in running the investigation than to risk being burned again by another Jew with perhaps questionable loyalties.”

Shamai Leibowitz, a contract linguist for the FBI, was sentenced in 2010 to 20 months in prison for sharing classified documents with a blogger. (Courtesy of Shamai Leibowitz)

Shamai Leibowitz, a contract linguist for the FBI, was sentenced in 2010 to 20 months in prison for sharing classified documents with a blogger.

The judge in the case said the material was sensitive enough that even he was not privy to exactly what Leibowitz, a grandson of the Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, had disclosed.

Richard Silverstein, who publishes the Tikkun Olam blog and is sharply critical of Israeli policies, told The New York Times in 2011 that he was the recipient of the documents and that the leaks had to do with U.S. eavesdropping on the Israeli Embassy. The tapped conversations included talks with pro-Israel activists, diplomats and at least one member of Congress.

Silverstein said Leibowitz leaked because he thought the embassy’s bid to influence the Iran debate in the United States was improper.

Leibowitz, who now works at a suburban Maryland synagogue, vehemently denies Silverstein’s account. His disclosure, Leibowitz said in a June 2013 blog post, was prompted by concerns “that the FBI was abusing the rights of U.S. citizens.”

“The FBI were illegally violating people’s privacy and to my understanding they were breaking the law,” Leibowitz said in an email Wednesday to JTA. “What I revealed about the FBI was similar to what Edward Snowden revealed about the NSA. For obvious reasons, I cannot get into details. I revealed this information only because I could not in good conscience keep silent, and I thought the public had a right to know.”

Noah Cohen for decades was active in Washington’s Orthodox community, volunteering with the Jewish Community Relations Council, the Orthodox Union, the National Council for Synagogue Youth and the Hebrew Academy day school.

He also worked for the CIA, and to this day his son, Abba Cohen, the Washington director of Agudath Israel of America, does not know in what capacity.

“There was no work talk at dinner and I didn’t know any of his work friends,” Abba Cohen said.

Noah Cohen was proud of his work with the agency, which started during World War II when he was hired by its predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, because of his fluency in German. He also spoke Hebrew and Arabic.

“He looked like he belonged in the library,” the younger Cohen said. “He was scholarly, thoughtful and analytical, and extremely interesting. Just not the athletic, suave, martini-drinking type you see on TV.”

Cohen said his father was proud of his employer.

“He was a big supporter of the CIA and its work,” especially during the 1960s when there was heightened criticism of American involvement in overseas conflicts. “He was a big defender of the things they needed to do. He was convinced if everyone knew what they did, they would feel as he did.”

His father observed Shabbat and holidays and never complained of any discrimination, Cohen said. He would use vacation time for Jewish holidays, a common practice before the government grew more accommodating of religious practice. He decided not to take an overseas tour, perhaps stymieing his career, because he and his wife wanted to guarantee their children a Jewish education.

Occasionally a tidbit would come out. One trip overseas was canceled, Cohen recalled, because of a rash of kidnappings of diplomats. Another time the elder Cohen told the family that he found a way to attend services on Shabbat in whatever country he was in. He would read the papers and occasionally complain that what had crossed his desk on Tuesday labeled as top secret would appear in the newspaper on Wednesday.

Noah Cohen retired in 1971 at 54 and subsequently revealed a few more details, like the time he returned early from Central America because his cover was blown. Or the midnight call to quickly get to a safe house in Washington. He also showed the family pictures taken overseas when he was in disguise, including a toupee, false mustache and false mole. He also had a sense of mischief.

“My mother told us he once came home in disguise,” Abba Cohen said.

![]()