A Hebrew charter school takes a not-so-Jewish trip to Israel

Published October 27, 2017

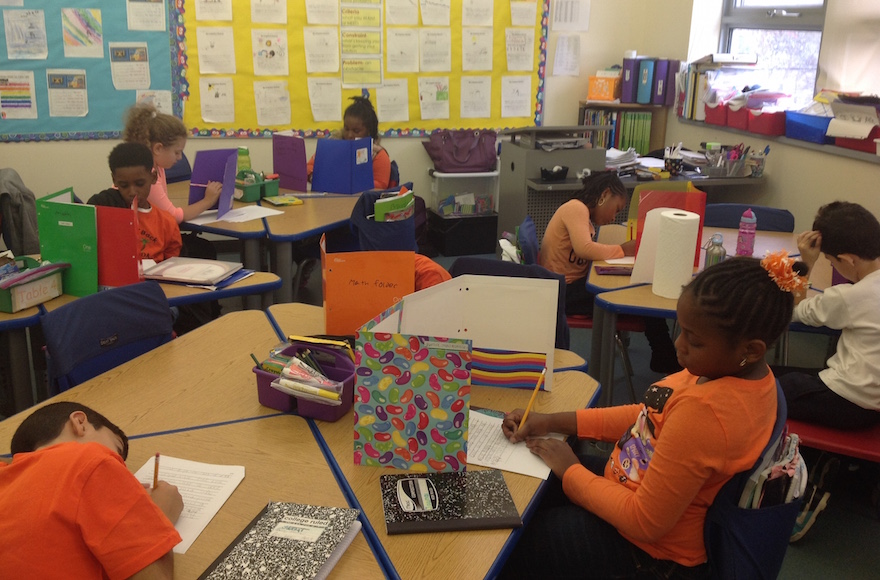

First graders learn Israeli dance at Hebrew Language Academy, a Brooklyn charter school that teaches Hebrew and Israeli culture, but not Judaism. (Ben Sales)

NEW YORK (JTA) — On her first trip to Israel next month, eighth-grader Melodee Pouponneau is excited to visit Tel Aviv and eat Israeli foods. She’s also looking forward to practicing Hebrew, her third language.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’ll be a stark change from her home life in Brooklyn, where she speaks Haitian Creole and typically eats foods from the Caribbean nation where her parents were born.

Pouponneau, 12, isn’t Jewish, but she’s confident she’ll be able to carry on a conversation with Israelis when she visits the Jewish state. As a student at Hebrew Language Academy, a Hebrew-language charter school in Brooklyn, she’s been studying Hebrew and Israeli culture since kindergarten.

“I feel excited because it’s not uncomfortable for me because I speak Hebrew,” she said. “If I go to Israel not speaking Hebrew at all, that would be weird.”

Pouponneau is one of 33 eighth-graders from two Hebrew-language charter schools who are traveling to Israel on a class trip. The trip aims to give the students a firsthand look at the language and culture they’ve learned about in class. But because the schools are publicly funded, the program has to straddle a thin line: Throughout the 10-day trip, the aim is to immerse students in Israeli culture — but without being overtly Jewish or taking a political stance.

ADVERTISEMENT

Unlike Jewish day schools, which are private, Hebrew charter schools receive taxpayer dollars and are free and open to students of all backgrounds. Because of that, they can’t give their students religious education — though they can teach a particular language, culture and history. The two schools taking the trip — Hebrew Language Academy and Hatikvah International Academy in East Brunswick, New Jersey — are both part of Hebrew Public, a national network of four Hebrew charter schools it directly manages and six affiliates.

During a reporter’s visit to the Brooklyn school earlier this week, first-graders were learning Israeli dance while third-graders took a Hebrew proficiency exam. Meanwhile, the eighth-graders — preparing for the trip — did a unit on sabich (pronounced sah-BEEKH), an Israeli egg and eggplant sandwich.

Mira Yusupov, a Hebrew teacher, explained that the curriculum eschews traditional grammar lessons in favor of learning everyday vernacular conversation.

“There’s no Alef-Bet,” she said, referring to teaching the Hebrew alphabet by rote. “If they’re going to a coffee place, we teach the skills rather than the language — how to order stuff.”

Yusupov, who will be accompanying the students on the trip, hopes the experience will bring Israeli culture to life. The 10-day excursion follows an itinerary with many of the same stops as Birthright, the free, 10-day trips to Israel for young Jewish adults.

The middle-school trip will start in Tel Aviv, with visits to a tech hub and outdoor markets. They’ll take a camel ride in a touristy Bedouin village, float in the Dead Sea, hike up to the ancient fortress of Masada, spend a few days in Jerusalem and then some time at a kibbutz up north.

But because the trip isn’t Jewish, it departs from the Birthright checklist. The kids won’t visit Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum — on a previous trip to Washington, they visited the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum — but will visit a mosque, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Via Dolorosa and a Druze village. They will also stop by Hand-in-Hand, a Jewish-Arab school in Jerusalem, and Kids4Peace, a youth group for Israeli and Palestinian kids. They’ll visit the Western Wall on Friday night, but won’t pray there, and that night’s dinner won’t include communal blessings over wine and challah.

“We’re not going to try to edit out anything Jewish, per se, but I think that the kind of reflections and conversations we have are not going to be around Jewish identity,” said Jessica Lieberman, Hebrew Public’s director of Israel studies. “We’re not going to delve into ‘What does it mean to be an American Jew who comes to see these things?’”

Hebrew Language Academy was founded in 2009 with private funding from Michael Steinhardt — who also funds Birthright — and other Jewish philanthropists who founded the Hebrew Public network. It’s one of about a dozen Hebrew-language charter schools nationwide. Now, the school runs entirely on public funds, and chooses its students by lottery from its local school district. Hebrew Language Academy estimates that about 50 percent of its students are Jewish, along with a large population of students of Caribbean descent.

Because of that, it faces the challenge of not being “too Jewish” on a daily basis. The school avoids teaching Judaism by focusing entirely on language instruction and Israel education, like learning about food, music, geography and history. But at first glance, the school could be mistaken for a Jewish day school: Hebrew phrases adorn the walls and the classrooms are named after Israeli cities, with Israeli and American flags hanging from the walls.

“We built a dual-language school with an appreciation of Hebrew language and Israel,” said Peter Katcher, the head of school. “The genesis of the [Israel] trip was as a culmination of this many years of study. The most important part of this is to have the respect and understanding of the culture.”

Third graders take a Hebrew exam at Hebrew Language Academy. (Ben Sales)

As such, while specifically religious issues will be avoided on the trip, students will dip their toes into the Israeli-Arab conflict. The kids will visit the embattled Gaza border town of Sderot and the Lebanese border, where students will hear a talk from a local security expert. They will also hear a lecture from a legislator from the Labor party.

“The conflict is obviously an important part of Israel and learning about Israel,” Lieberman said. “It’s not the main part of the trip. I also want to see what the students know and what their questions are because we built into this trip lots of different encounters with lots of different people.”

And while Katcher said the group will stay out of the West Bank, they will visit eastern Jerusalem, which Israel has annexed but the international community views as occupied territory. The itinerary includes a stop at the City of David, a Jewish-run archaeological park open to tourists in the hotly contested eastern Jerusalem Arab neighborhood of Silwan. Lieberman said the visit will focus on archaeology, and that the school didn’t consider the park’s location while planning the trip.

A trip to Israel is not inherently political or religious — just as a trip to France and the Notre-Dame Cathedral isn’t inherently Catholic, said Shaul Kelner, a Jewish studies professor at Vanderbilt University, who focuses on diaspora Jewish travel to Israel.

“Language and culture are intimately connected,” he said. “The language instruction overall is never just about learning to speak in a different code. It’s about learning the culture connected to that code.”

As it happens, for at least some of the kids going on the trip, the complexities of politics and religion are at best an afterthought. Justin Matushansky, 14, went to Israel last year to celebrate his bar mitzvah with his family. He’s mostly excited to eat when he returns in November.

“They have really good burgers,” he said. “They had free samples of falafel. I want to try pita for falafel.”