9 iconic sites that celebrate American Jewish history

Published July 1, 2016

Clockwise from top left: Bob Dylan’s childhood home in Hibbing, Minn. (Wikimedia Commons), Temple Beth Sholom in Elkins Park, Pa. (Wikimedia Commons), Canter’s Deli in Los Angeles (Flickr Commons), Beth Jacob Cemetery in Galveston, Tx. (Wikimedia Commons).

Monday is Independence Day in the U.S. That means it’s time for many Americans to take a day off, watch some fireworks and grill large amounts of meat to enjoy with friends and family.

ADVERTISEMENT

Of course, the 4th of July — which commemorates the adoption by the Continental Congress of the Declaration of Independence — is one of the most important dates in American history. And since that day in 1776, Jews have made their mark on the U.S. in myriad ways. So why not take a moment to celebrate the history of Jewish people on these shores?

Granted, the American Jewish story may be a complicated, sprawling one. Still, some special sites manage to symbolize decades of Jewish struggle, migration and triumph — from the birthplaces of cultural icons to the earliest examples of houses of worship.

If you’re not already on vacation as you read this, you may not want to join the 43 million Americans who are expected to hit the highways this holiday weekend. But good news: There’s still nine weeks left of summer; plenty of time to squeeze in a road trip or two. So for those feeling adventurous, here are nine places to visit that best connect the Jewish story to the American story.

Lower East Side Tenement Museum, New York, New York

A view of the front of the Tenement Museum. (Wikimedia Commons)

A trip to Ellis Island may tell you how your ancestors arrived in the United States, but a visit to the Lower East Side Tenement Museum may show you how they lived. The narrow, five-story apartment building at 97 Orchard Street preserves an era when almost 240,000 people crowded into each square mile of the Manhattan neighborhood. Between 1880 and 1924, nearly 75 percent of the 2.5 million mostly Ashkenazi Jews who came to the United States took up residence on the Lower East Side.

ADVERTISEMENT

Among the museum’s three restored apartments is one recreating the 1878 home of the Gumpertz family, Jewish immigrants from Prussia. The three-room, walk-through flat — tiny front parlor, kitchen, combination living room-bedroom — shows where Nathalie Gumpertz raised her four young children while making dresses to keep them clothed and fed. (Gumpertz passed away in 1894 at age 58.) Some of the museum’s guided tours include costumed actors who reenact daily life from the period.

The museum, a National Historic Site, recalls the poverty and struggles of immigrants, as well as a period during which “America was a safety valve and a haven, a place of renewal and a source for support” for Eastern European Jews, as Irving Howe wrote.

Touro Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island

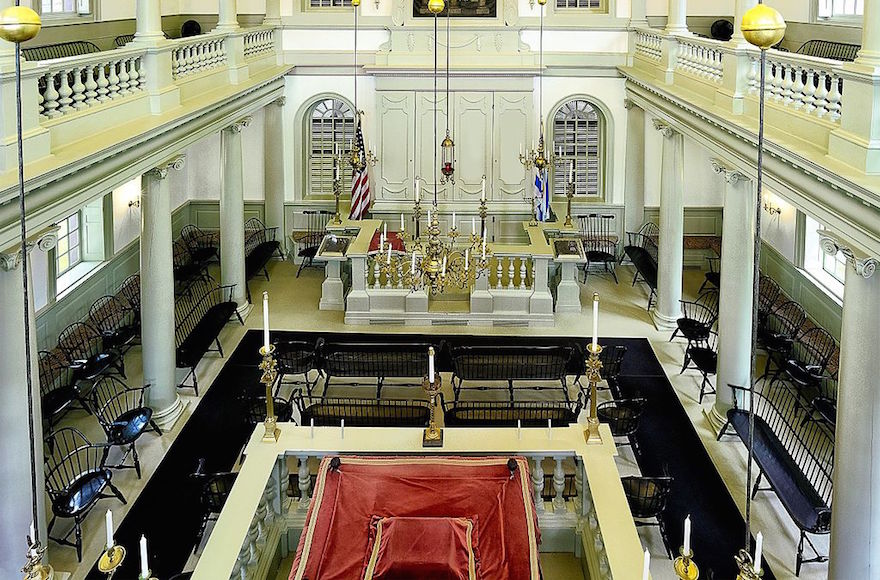

A view inside the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island. (Wikimedia Commons)

The oldest synagogue building in North America is the Touro Synagogue of Newport, Rhode Island, which dates to 1763.

The congregation’s history is a rich one: A newly elected President George Washington famously wrote a letter to the synagogue’s warden in 1790 declaring that the U.S. government “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance…May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants.” The letter remains one of the earliest emblems of American religious liberty and the separation of religion and state.

The synagogue, built by Spanish and Portuguese Jewish immigrants (and renovated in 2006), has been in the news recently: Congregation Jeshuat Israel, which worships at the synagogue, wanted to sell some valuable, historic ornaments that adorn their Torah scroll. Congregation Shearith Israel in New York, which has acted as Touro Synagogue’s financial trustee for over 200 years, tried to stop the sale. In May, a federal court sided with the hometown congregation.

Debates aside, the building still holds Orthodox services and offers tours each week.

Temple Beth Sholom, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania

An exterior shot of the Beth Sholom synagogue. (Wikimedia Commons)

During his storied career, Frank Lloyd Wright designed only one synagogue: the futuristic, pyramidal Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Penn. The striking National Historic Landmark features an outdoor fountain, two sanctuaries and a complex array of geometrical designs in its walls and ceiling.

Aside from being an architectural masterpiece, the building is also an emblem of 20th-century suburbanization and the Jewish attempt at assimilation into white middle- and upper-class America. After World War II, government policies aimed at reducing the cost of suburban construction — along with expanding highways and the booming auto industry — brought whites out of cities in massive numbers. Jews joined the migration, hoping to move beyond their past as immigrant outsiders who were often excluded from bastions of privilege, like universities, country clubs and, sometimes, jobs.

The Beth Sholom congregation began in northern Philadelphia in 1919 but moved to Elkins Park in the 1950s (the final Wright-designed synagogue was not completed until just after his death, in 1959). It has continued to serve its Conservative congregation ever since.

Gomez Mill House, Newburgh, New York

The mill wheel at the historic Gomez Mill House in Newburgh, New York. (Wikimedia Commons)

A Sephardic merchant named Luis Moses Gomez, whose family had been forced out of Spain during the Inquisition, bought 1,000 acres of land in Newburgh, New York in 1714. He and his two sons, Jacob and Daniel, became well-known traders in New York and eventually accumulated 2,400 acres of land. They built a trading house made of stone and an adjacent mill next to a creek that became known as “Jew’s Creek.” The family traded timber and lime with Algonquin Native Americans, travelers and local residents.

Today, the Gomez Mill House remains one of American Jewish history’s best-kept secrets and is likely the oldest Jewish site in North America. Subsequent owners, such as the Dutch colonist Wolfert Acker and 19th-century landowner William Henry Armstrong, built multiple floors on top of the original house structure, but it remains a pristine historical artifact. School children visit every year to experience what SUNY professor Harry Stonebeck has called “a most dramatic and irreplaceable incarnation of American history.”

Beth Jacob Cemetery, Galveston, Texas

Beth Jacob Cemetery in Galveston, Texas. (Wikimedia Commons)

The island city of Galveston is known as Texas’s beachy tourist destination on the Gulf of Mexico. But it was also one of the first havens for Jews in North America.

A Portuguese-Jewish merchant named Jao de la Porta financed one of the first European settlements on Galveston in 1816 and the French-Jewish pirate Jean Lafitte took over the island the next year during the Mexican War of Independence. Lafitte turned it into a pirate colony and smuggling base until he lost control of it in 1821.

Several decades later, Galveston would become one of the largest Jewish communities in the country. By the turn of the 20th century, after anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe spurred a wave of Jewish immigration to the United States, East Coast cities like New York were already becoming crowded and unsanitary. In response, with the aid of New York financier Jacob Schiff and the Galveston Jewish community’s Reform rabbi, Henry Cohen, the Galveston Movement plan was launched in 1907. Through 1914, the plan diverted over 10,000 Jewish immigrants to Galveston — about a third of the number who immigrated to the then British Mandate of Palestine during the same period.

Eventually, many of these immigrants moved away to different cities. But the Jewish community’s imprint lives on: The Conservative synagogue Congregation Beth Jacob, with its historic cemetery, remains active, as does Congregation B’nai Israel, the oldest Reform synagogue in Texas.

Canter’s Deli, Los Angeles, California

Canter’s Deli in Los Angeles. (Flickr Commons)

Depending on whom you ask, the American Jewish deli has been arguably as important a meeting place for Jews as the American synagogue — perhaps even more important. For many religious and secular Jews of Hollywood’s Golden Age and beyond (from Arthur Miller to Henry Winkler to Michael Mann) Canter’s Deli in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles has been a lasting link to their Jewish roots.

Canter’s is also a symbol of American Jewish culture’s westward migration. When the Jersey City deli owned by Ben Canter and his two brothers failed after the stock market crash of 1929, the Canters moved west like many other Jews who were hoping for a fresh start. Now, having been featured in Jewy shows such as “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and “Transparent,” the deli is as prominent a symbol as any of “Jewish L.A.” While the city’s homegrown culture is sometimes maligned as an imitation of New York’s, it has clearly taken on a flavor of its own.

The Art Deco restaurant is a monument in its own right, with a famously entrancing autumn leaf-patterned ceiling and a neon sign from the 1950s — and by L.A. standards, that’s practically ancient.

Congregation Mikveh Israel, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

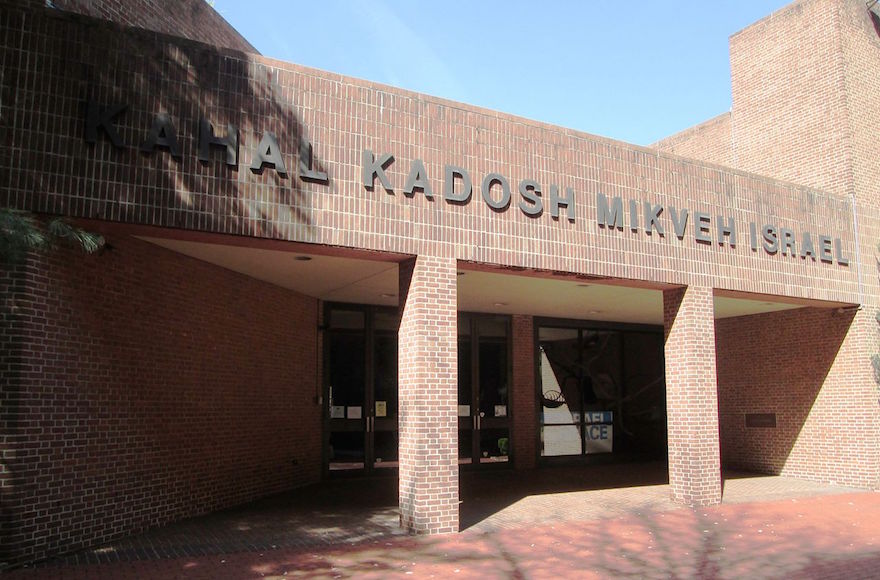

Congregration Mikveh Israel is the oldest continuous congregation in the U.S. (Wikimedia Commons)

Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia calls itself the “Synagogue of the American Revolution,” and with good reason: Founded by Spanish and Portuguese traders in the 1740s, the synagogue served as a refuge for Jews from New York, Richmond, Charleston and Savannah during the War of Independence. Haym Solomon, who helped finance the war, and the Gratz brothers, who supplied the Continental Army, were members.

Now the oldest continuous congregation in the United States, the synagogue still holds fast to the Spanish-Portuguese traditions of its founders, and honors the legacies of Sephardic Jews who formed the original Jewish communities in the New World.

Today, you can tour the building it has occupied since 1976 — close to its original site, and not far from the exceptional National Museum of American Jewish History — and you’ll be shown a white marble ark enclosure dating from 1859, a kohane’s ceremonial chair donated in 1816 by dentist and “bleeder” Moses Lopez and an oak reader’s lectern that may date back to 1782, when the congregation was in its first building.

Bob Dylan’s childhood home, Hibbing, Minnesota

The Zimmerman family home in Hibbing, Minnesota. (Wikimedia Commons)

Has there been a more iconic Jewish artist or storyteller than Bob Dylan? The man born Robert Zimmerman and nicknamed “The Bard” has connected generations of Jews to the history of American music, paving the way for the success of other Jewish folk songwriters, from Paul Simon to Leonard Cohen. His story — from the small town of Hibbing, Minnesota to the clubs of New York City’s Greenwich Village — is an unlikely Jewish but quintessentially American one.

The annual Dylan Days festival (a celebration complete with tours of Dylan’s former home in Hibbing) ended in 2014 and Zimmy’s Restaurant, which was decorated with Dylan paraphernalia, shuttered the same year. But Duluth, the city where Dylan was born, still holds a Dylan Fest, which includes a bus tour of Hibbing — the town only 90 minutes away, where the singer formed his first bands and covered songs by the likes of Elvis Presley and Little Richard.

The house is privately owned but there’s nothing stopping you from passing by to take an exterior pic or two — then move on, like a rolling stone.

Congregation Sherith Israel, San Francisco, California

A view of Temple Sherith Israel in San Francisco, California. (Wikimedia Commons)

For more than 150 years, Americans have been going west to embrace the new — or, at least, escape the old.

Driving the point home is a monumental stained-glass window in the Spanish revival main sanctuary of Sherith Israel in San Francisco, a Reform temple that survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake (and served, for 18 months after that disaster, as the city’s courthouse). The synagogue was established by Jewish pioneers during California’s Gold Rush, and the current building was consecrated in 1905.

The window shows Moses and the Israelites on the way to Sinai. Look closely, though, and you’ll see that’s not the Wilderness of Sinai in the background — it’s El Capitan, the iconic towering cliff in the Yosemite Valley. The 200 families who founded the synagogue weren’t turning their backs on tradition; the window is a midrash — an alternative biblical story — that conflates the Jewish yearning for a promised land with the American dream of new beginnings.