7 Elie Wiesel books that show the range of his influence

Published July 7, 2016

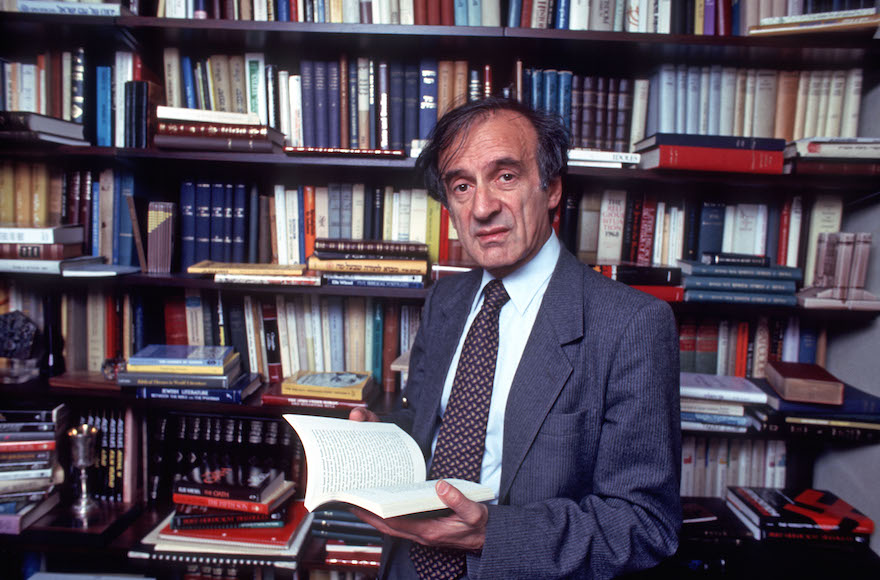

Elie Wiesel, the author of over 50 books, in the study of his New York City home, Oct. 14, 1986. (Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images)

Most people know Elie Wiesel as the author of “Night,” one of the first published autobiographical accounts of what life was like inside Nazi concentration camps. The book, which helped shape the American understanding of the effects of the Holocaust, has since become a staple on high school reading and best-seller lists.

ADVERTISEMENT

But Wiesel, who passed away Saturday at 87, wrote more than 50 books of fiction and nonfiction — and not all were focused on his harrowing experiences in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald camps. He was interested in political activism, philosophy and religion, and his books ranged from novels that question the existence of God to a journalistic expose on the plight of Soviet Jewry.

Here’s the Wiesel reading list everyone should know.

“Night” (1960)

Arguably the most influential book on the Holocaust, “Night” brought the atrocities faced by Jews in the concentration camps to the forefront of American consciousness. The book’s narrator, Eliezer, chronicles his hellish experience in Auschwitz through a lyric, fragmented style now acknowledged as a “genuine artistic achievement.” Young Eliezer survives the torturous labor and murderous Gestapo, but his belief in God is forever altered.

Along with “Night,” these two works form a trilogy that deals with the Holocaust and its aftereffects. Although “Night” has been variously described as a memoir, a novel and a “testimony” (by Wiesel himself), these two books are decidedly fictional. In “Dawn,” a Holocaust survivor moves to prestate Israel (what was then the British Mandate of Palestine), joins the Irgun (a predecessor of the Israel Defense Forces) and struggles with an order to execute a British officer. In “Day,” a Holocaust survivor comes to terms with his World War II experiences while recuperating in a hospital after being injured in a car accident.

“The Jews of Silence” (1967)

In 1965, Wiesel was sent to the Soviet Union by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. His observations on the plight of Jews there — who suffered from anti-Semitic discrimination and were forbidden to publicly practice their religion — became the catalyst for an activist and political movement in the West that eventually helped thousands migrate to Israel and other countries in the 1980s.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I would approach Jews who had never been placed in the Soviet show window by Soviet authorities,” he wrote. “They alone, in their anonymity, could describe the conditions under which they live.”

“A Beggar in Jerusalem” (1970)

Wiesel turned his imagination to the Six-Day War in this novel originally written in French, which won France’s prestigious Prix Medicis award. Wiesel, who worked as a journalist in France after being liberated from Buchenwald, muses on suffering and loss through the protagonist David, a Holocaust survivor who runs into a group of beggars near the Western Wall days after the war. Their stories bring him back to his painful memories of World War II and fighting Arab soldiers in the 1967 war.

“Souls on Fire: Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters” (1972)

Wiesel, who struggled with his faith after his Holocaust experiences, never lost his fascination with Hasidism, the ecstatic spiritual movement of which his grandfather was a follower. “Souls on Fire” is a collection of lectures on the lives of the early Hasidic masters from Eastern Europe, starting with the movement’s founder, the Baal Shem Tov, and including storytelling rabbis and kabbalists who continued the tradition. The portraits combine history and legend, and along the way, Wiesel wrestles with the question of whether men can speak for God.

“The Trial of God” (1979)

This eerie story — one of the very few plays Wiesel wrote — is set in a Ukrainian village in 1649, where a Cossack pogrom has just wiped out all but two of the town’s Jews. Instead of staging a Purim play, the survivors — along with three actors — stage a mock trial of God.

Although the play is set in the 17th century, Wiesel has said he based it on an event he witnessed at Auschwitz, when three rabbis came together to indict God for allowing the Holocaust to happen.