The Jewish doctor who said “no” to the corset

Published July 5, 2021

This story originally appeared on the website for the National Library of Israel. Repblished with permission.

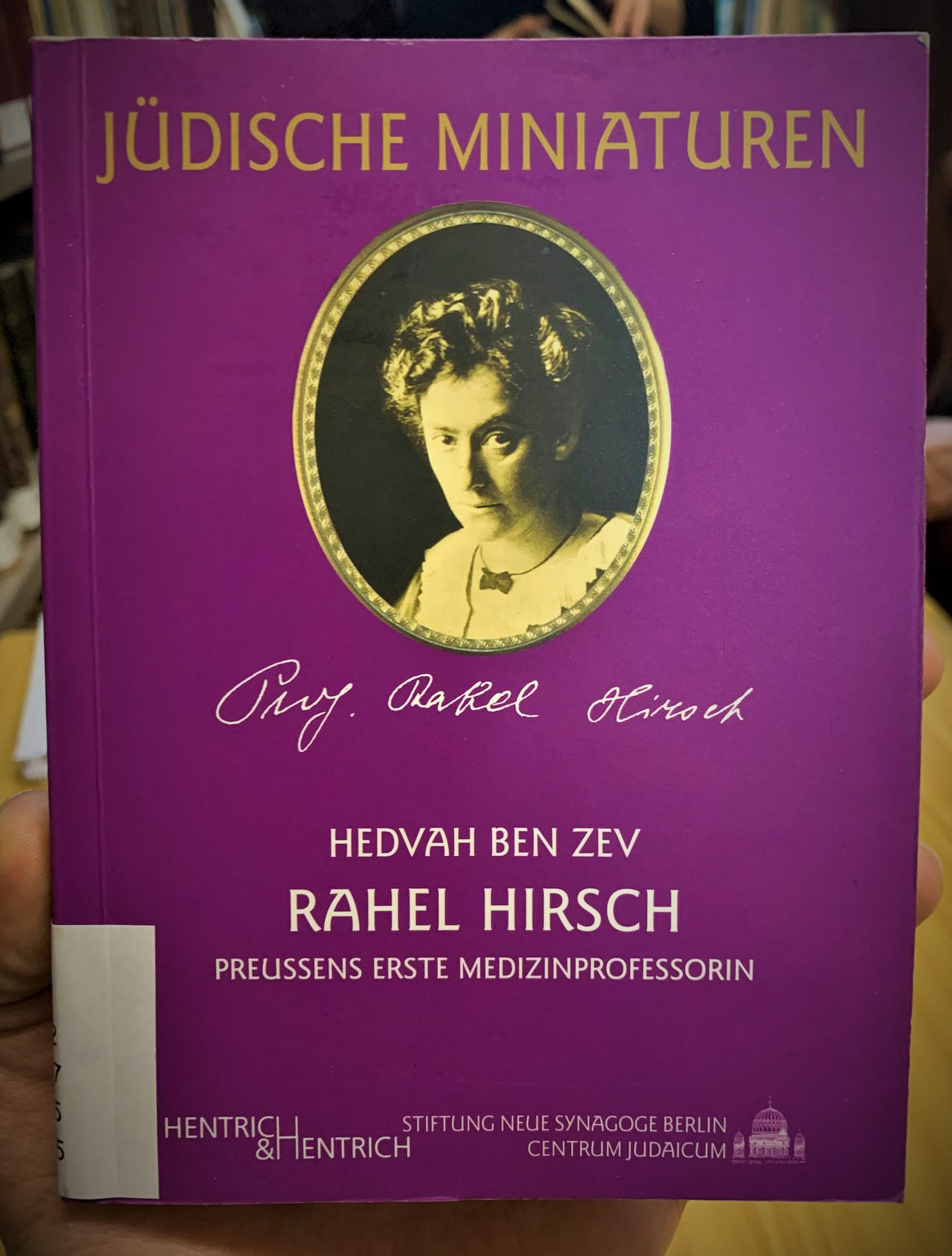

The life story of Dr. Rahel Hirsch could easily be the plot of a Hollywood tearjerker. This groundbreaking pioneer was born to a Jewish family in the Kingdom of Prussia in the late 19th century. Her origin and perhaps having been born in the wrong place at the wrong time forced Hirsch to face many hardships during her life. First, she had to fight her way into the medical world. Later on, she continued to struggle with attempts to delegitimize her as a woman in the field.

Rahel Hirsch was the daughter of a school administrator and was originally sent to study education. However, her mind was always drawn to science. More than anything, she wished to become a physician. Unfortunately, the German Reich at the time forbade women to attend university studies. But why?

ADVERTISEMENT

Back then, many men believed women should not be allowed to engage in academic professions, certainly not medicine, since they were simply perceived as unfit to do so – both mentally and physically. Those who advanced this “scientific” theory, pointed for example, to the fact that the female brain was smaller on average than that of the male (while mistakenly disregarding the size of the brain in relation to the rest of the body).

Under these restrictions, and in order to realize her dream, Rahel Hirsch left her home and everything she knew and traveled to Switzerland, where she was permitted to study medicine. In 1903 Hirsch received her long-desired medical license and from that moment on broke professional and gender-related boundaries. In 1907 she was accepted to work as an intern at the medical clinic at the Charité – a university hospital in Berlin. She was only the second woman to be hired by the institution in its entire history.

Under these restrictions, and in order to realize her dream, Rahel Hirsch left her home and everything she knew and traveled to Switzerland, where she was permitted to study medicine. In 1903 Hirsch received her long-desired medical license and from that moment on broke professional and gender-related boundaries. In 1907 she was accepted to work as an intern at the medical clinic at the Charité – a university hospital in Berlin. She was only the second woman to be hired by the institution in its entire history.

She later became the first person to find indications of starch particles in blood and urine and thus was able to refute the widely accepted notion that only liquids could penetrate the kidneys. The discovery that certain medical conditions could cause microscopic cells to penetrate the kidneys and exit via urine was invaluable to the medical world. She recorded her findings in a study on metabolic processes and diseases but instead of being acclaimed for them, she was mocked by her colleagues – because she was a woman.

It was a closed, patriarchal society, and so despite her accomplishments, when Hirsch presented her study at a meeting of the Charité’s directors, she was ignored by the doctors, who believed women to be of inferior intelligence. Nevertheless, she managed to move ahead and in 1908 was appointed head of the Charité’s medical clinic. Sadly, despite her new senior position, she was not paid for her services.

Hirsch soon left the Charité and opened her own private clinic in Berlin, where she installed modern X-ray equipment; this attracted wealthy clients and allowed her to live comfortably. In 1913 she became the first woman to receive the title “professor” in Prussia. However, she hadn’t seen the last of her challenges yet.

ADVERTISEMENT

Rahel Hirsch was a Jewish woman. As a result, she was barred from teaching medicine in Germany during this period. In order to expose her colleagues to her ideas regarding women’s health – ideas that were not yet accepted in academic circles – she wrote a treatise titled Physical Culture of Women.

The essay focused on refuting prejudiced conceptions about women’s exercise and how they should dress. She recommended clothing that fit the female physique naturally, without corsets; clothing that enabled a normal blood flow. Hirsch tried to draw attention to women’s health by raising awareness of hygiene, nutrition and exercise, though it seems the primary focus of the essay was to prove that women were no less intelligent than men. In an article published in the Munich Medical Weekly, she wrote her colleagues that the theory that males were more intelligent than females was unsubstantiated and that any difference between the mental capabilities of men and women was not biologically determined but rather a matter of faulty education. She also suggested they look at women not only from a gynecologic point of view, as women’s medicine was not all about female genitalia.

When the Nazi prosecution of Jews grew more intense, Hirsch lost many of her clients, who were now afraid of associating with Jews. Also, her authorities as a physician were gradually taken away from her. This process reached a peak in 1938 when she was 68 years old: Hirsch’s medical license was taken from her. When she heard she was going to be arrested, Hirsch fled to live with one of her sisters in London, though in England she could not practice medicine. Instead, she worked as a librarian, while also translating and working as a laboratory assistant. During the war, she lived in Yorkshire before returning to London once the hostilities were over.

The events that occurred in her homeland and the atrocities committed against the Jews, along with the restriction on practicing the one thing she truly loved and for which she had worked her entire life – drove her to madness. Hirsch was hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital, where she died on October 6th, 1953. She was buried anonymously in one of the city’s Jewish cemeteries.

A few years after her passing, in 1957, a research assistant from Charité named Gerard Volkheimer, who would later become a professor, came across Hirsch’s study and published it under the title the “Hirsch Effekt”. Approximately four years after she died, Rahel Hirsch’s work and contribution to science were finally recognized.

More From The National Library of Israel

-

‘Toyve the Black Cantor’ and His 1930 World Tour

-

Who Was the Real Model for Kafka’s Gregor Samsa?

-

The Jewish Book That Revealed the Secrets of the Heavens