Was “Lawrence of Arabia” really a Zionist?

Is it possible that this iconic pro-Arab figure eventually became a Zionist? And what organization was likely responsible for his change of heart?

Published January 3, 2023

It was around the time of the First World War. The waning Ottoman Empire still ruled over the Land of Israel, but the British were already waiting in the wings in Egypt. In this article, we will discuss the British officer and archaeologist whose name is the stuff of legend and mystery. The life of this important historical figure was documented in an Oscar-winning film, his image was immortalized on the cover of a Beatles album and even Winston Churchill hailed his autobiography as ranking “with the greatest books ever written in the English language”.

You must have guessed by now who it is.

Here in Israel, this individual’s deeds are less familiar, probably because he is generally considered a pro-Arab figure. But, as we have been taught, one must always choose a side—good or bad, them or us. Because whosever supports Arab independence cannot possibly support Jewish nationalism simultaneously. Right?

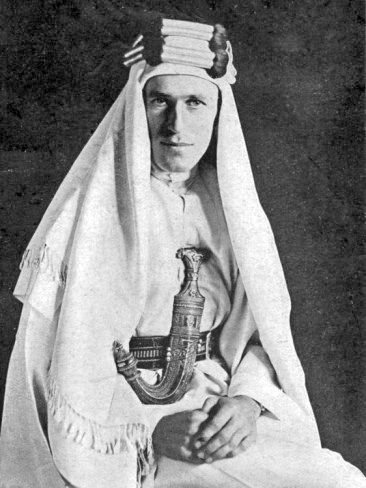

I am of course referring to none other than Thomas Edward Lawrence, who most of us know as “Lawrence of Arabia”, leader of the Arab Revolt, hero of the classic Hollywood film, the man whose face appeared on the cover of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album and who began his autobiography Seven Pillars of Wisdom with a cryptic poem dedicated to someone with the initials S.A.

In addition to the above, Lawrence was also an archaeologist. In 1911, while participating in archaeological excavations in northern Syria, the 23-year-old Lawrence even wrote a diary documenting his travels in the area, which was later published. He would refuse a knighthood from the King of England because he felt betrayed by the British government. His premature death at age 46 in a mysterious motorcycle accident practically guaranteed his stardom and cemented his legacy to this day.

So who was Lawrence of Arabia?

Let’s start from the beginning, Thomas Edward Lawrence was born in 1888 in Wales. His father, Sir Thomas Chapman, was a minor nobleman, and his mother, Sarah Junner, was the family governess. Chapman left his wife and family for Junner, and together they wandered from place to place. These events taught Lawrence the importance of keeping secrets from an early age. He had to keep the story of his birth under wraps in order to avoid the shame and social repercussions of being born out of wedlock. Later, this illegitimate son managed to break the glass ceiling of the British class system and enter Buckingham Palace through the front door.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lawrence graduated with honors from Oxford where he majored in history. He arrived in the Middle East for the first time in 1910 to join the British Museum’s archaeological excavations at Carchemish. There he met the archaeologists Leonard Walley (whom we will return to later) and David Hogarth, who was impressed with the young man. During Lawrence’s stay in the region, he learned the Arabic language as well as Arab customs and culture. These skills came in handy later and helped him acquire the legendary name by which he is known in popular culture.

With the outbreak of World War I, Lawrence was drafted into the British Army. Given the rank of major, he began working as an intelligence officer. In 1916, he was attached to the Arab Bureau in Cairo, where he again crossed paths with David Hogarth. Hogarth’s predecessor as head of the bureau was Mark Sykes – the very same Mark Sykes responsible for the Sykes-Picot agreement that would divide the territories of the former Ottoman Empire between Great Britain and France.

At the time, the British had been working to mobilize Arab support for the war effort. Toward that end, they hoped to recruit the Arab Hashemite faction led by Hussein Bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, to their side. Eventually, an understanding was reached with the Hashemites who, for their help, were promised control over the entire area south of Turkey—a vast Arab kingdom that would stretch from the Arabian Peninsula to the region of Syria (including the Land of Israel).

Lawrence had played a key role in formulating this agreement with the Hashemites. But he had been kept in the dark about the Sykes-Picot agreement, and felt betrayed when he learned of its contradictory terms. In his anger, he revealed its contents to the Hashemites. This secret move by the British was the first breaking point for Lawrence with the empire he himself represented. He became distrustful, among other things because he saw the duplicity as a betrayal of British values.

General Edmund Allenby sent Lawrence to help the Arabs during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire and together with Ali’s son, Faisal, he commanded a group of several thousand fighters equipped by the British. The campaign that began in the Arabian Peninsula ended with the occupation of Damascus and the entire eastern flank. However, Damascus was part of the territory that France was to receive according to its agreement with Britain. Lawrence knew this, but it did not prevent him from assisting in the conquest of Damascus and supporting Faisal’s claim to be crowned King of Syria. Lawrence was in essence attempting to thwart the Sykes-Picot agreement.

What Did the British Do?

The Arab Revolt was an acclaimed success, and the Hashemite forces were able to conquer Aqaba, helping the British in their conquest of Palestine – the Land of Israel. However, Sharif Hussein’s demand for the establishment of a large Arab kingdom encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, was rejected outright. The French recaptured Damascus and expelled Faisal, while the British stood by and did nothing. This, for Lawrence, was the second betrayal.

At this point, it is also important to mention the “Nili” underground organization—the spy network in the Hebrew settlement in the Land of Israel that was operating at the same time and in parallel. The underground was in contact with Lawrence’s colleague, the archaeologist Leonard Walley. Both groups pursued the same goals: cooperation in return for the promise of a state. Nili was providing broad intelligence that greatly contributed to the British effort. What was Lawrence’s view of this?

In the end, the British and French took over most of the territories promised to Sharif Hussein and divided them according to the Sykes-Picot agreement. However, Lawrence and Hussein also had some success: Hussein’s two sons were crowned kings—Abdullah over Jordan (the Hashemite dynasty rules Jordan to this day) and Faisal over Iraq. Lawrence, however, considered the agreement a betrayal by the British, and when he was summoned to Buckingham Palace to receive a knighthood after the war’s end, he made a public show of his disapproval by declining to accept it, a move that infuriated and embarrassed King George V. Nevertheless, when he was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1935, the entire nation paid tribute to him. He has since remained a legend in the eyes of many Britons, his portrait on the cover of the Beatles album being just one example of his iconic status in popular culture

Now for the part that might come as a surprise to many readers. Lawrence of Arabia was not only pro-Arab. He was also supportive of Zionism, though perhaps not from the beginning. Lawrence underwent a change in his opinion about the Jews in the region, likely due in part to his conversations with Walley who told him of the Jewish aid Britain had received in the war effort, such as the work of the Nili underground.

Towards the end of the war, Lawrence developed different loyalties. Having begun to see His Majesty’s Government as betraying its allies, he transferred his loyalty to the Hashemites. At this time, while rethinking his worldview, Lawrence also underwent a change in his attitude towards the Jews. If before the war he discounted them, now, inspired by Aaron Aaronsohn and his friends in the Nili underground movement, he saw them as brave, wise and courageous. The shift did not end there. Lawrence used his power and influence to change the face of the Middle East.

He organized the meeting between Chaim Weizmann, president of the Zionist Organization, and Prince Faisal, in which the Prince renounced his attachment to the land west of the Jordan River. He convinced Churchill to change the Sykes-Picot agreements so that they left out the Land of Israel. And at the Cairo Conference in 1921, in which the formal implementation of the Balfour Declaration was finally concluded, he demanded that a mandatory territory remain, including a national home for the Jewish people. Lawrence even envisioned the Jews playing an important role in the Middle East. In an interview he gave to a local London Jewish newspaper on the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, he said: “Speaking entirely as a non-Jew, I look on the Jews as the natural importers of Western leaven so necessary for countries of the Near East.”

Lawrence also spoke about the establishment of a future Jewish state: “…if a Jewish state is to be created in Palestine, it will have to be done by force of arms and maintained by force of arms amid an overwhelmingly hostile population.’” In this, he and Aaronson shared the same thinking, but it is doubtful whether they ever discussed it together.

Once Lawrence himself realized that the aforementioned arms could be Jewish rather than English weapons, he gradually adopted a more pro-Zionist approach. It is also worth noting that Aaron Aaronsohn had met Lawrence when they both worked for British intelligence. Aaronsohn disliked Lawrence because he thought he was against the Zionist idea, and Lawrence didn’t particularly like Aaronsohn either. Aaronsohn envisioned a new Middle East after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, including a Jewish-Armenian-Arab partnership, in which the Armenians would be a mediating factor between the Jews and the Arabs. Aaronsohn saw the importance of an Armenian state mainly in view of the genocide that had been perpetrated against them. He shared his thoughts with Sykes himself. We will never know how Aaronsohn might have reacted to Lawrence’s support for the Zionist cause because he died in a plane crash in 1919 over the La Manche channel on the way to the Paris Peace Conference. His body was never found.

Opinions about Lawrence of Arabia differ depending on how one views history. One thing is certain, Lawrence of Arabia, who was born “a social outcast,” appreciated the loyalty and integrity of smaller nations, and he abhorred duplicity. He believed in his path and worked for the good of the common people. One would assume that these traits developed in reaction to his own pain and shame from being thought inferior simply because of the circumstances of his birth.