From Texas to Missouri: A Crown Heights story of love, memory and murder

Published August 31, 2022

Rabbi Avraham Lapine describes his childhood in broad, simple terms. His earliest years often seem as distant to him as the noisy, asphalt streets of his native Brooklyn, N.Y., are from the quiet, suburban green of his home today in Columbia, Mo.

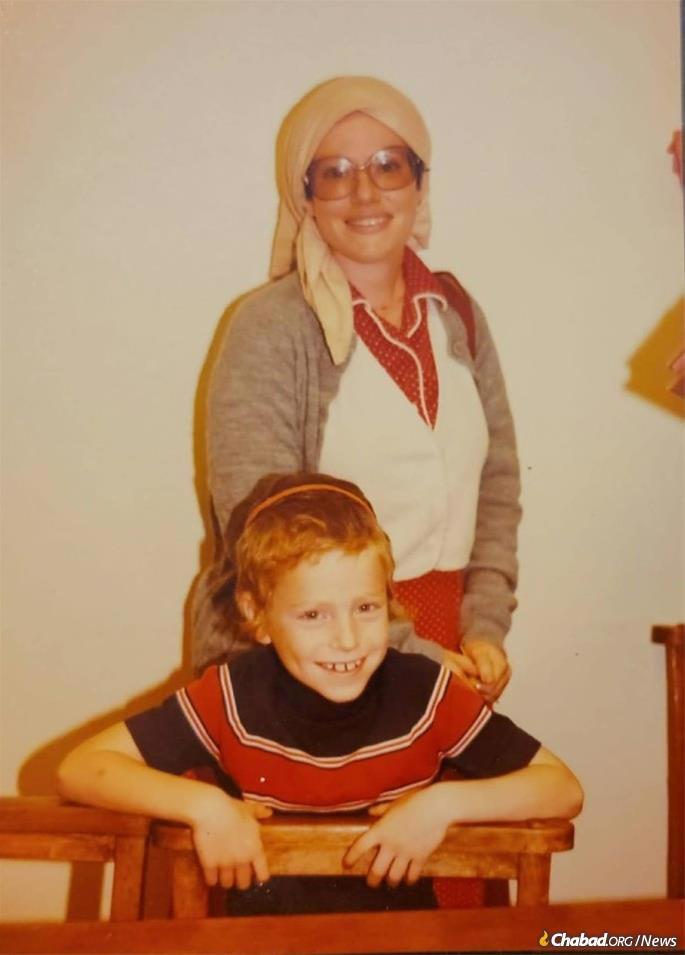

“I was just this fun-loving kid. I just enjoyed being around family, coming home, eating my favorite supper,” recalls Lapine, who co-directs Chabad-Lubavitch at the University of Missouri with his wife, Channy. “At 5-years-old, I was old enough to know I no longer wanted to be a fireman or something but didn’t really think about the future.”

There are bits and snatches of memory: summers in the Catskill Mountains; playing in the schoolyard; his mother, Pesha Leah Lapine, saying Tehillim (Psalms) in a rocking chair after the Shabbat meal. Of this last memory, he is less sure if it is his own or if it is something he assimilated after hearing about it frequently from others.

ADVERTISEMENT

There is, however, one day that stands out in sharp contrast to the haze of the others.

On a chilly Thursday, Feb. 6, 1992, Lapine returned from kindergarten at around 4 p.m. The family’s apartment at 680 Lefferts Ave. in Crown Heights was on the first floor of a two-story red brick house. Shaded by two large oak trees, it was the only house on the block with an awning, a large green one that covered the porch, as if to shield its occupants from the outside.

Getting off the bus from yeshivah, he walked up the steps to the front porch and pushed the front door. It was locked. Several large bags of groceries sat on the porch, evidence of his mother’s pre-Shabbat shopping and a telltale sign that someone was home.

Lapine didn’t think much of it. Instead, he stopped to rummage through the bags. “I just wanted to see what my mother bought, if she got any of the treats I liked,” he says. He then proceeded to the side door on the left of the home, only to find that entrance also locked. It was then that Lapine heard his sister, Sarah Chana, just 2-years-old, crying.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I started screaming, ‘Mommy open up,’ ” recalls Lapine, his cries echoing those of his sister. “But still there was no answer.”

Moving on to the backyard, he discovered an open window. Stacking the Little Tikes seesaw onto a small table, he tried, unsuccessfully, to climb into the window.

That’s when a neighbor, out to take her own children off the school bus, came over. Hearing the cries of Sarah Chana and seeing the young Avraham struggling to get in, she hoisted him through the open window.

“I stood on her hands and pulled myself through the window,” says Lapine. “There I could see the long hall of the house, and then at the end of the hall, something no child should ever see…”

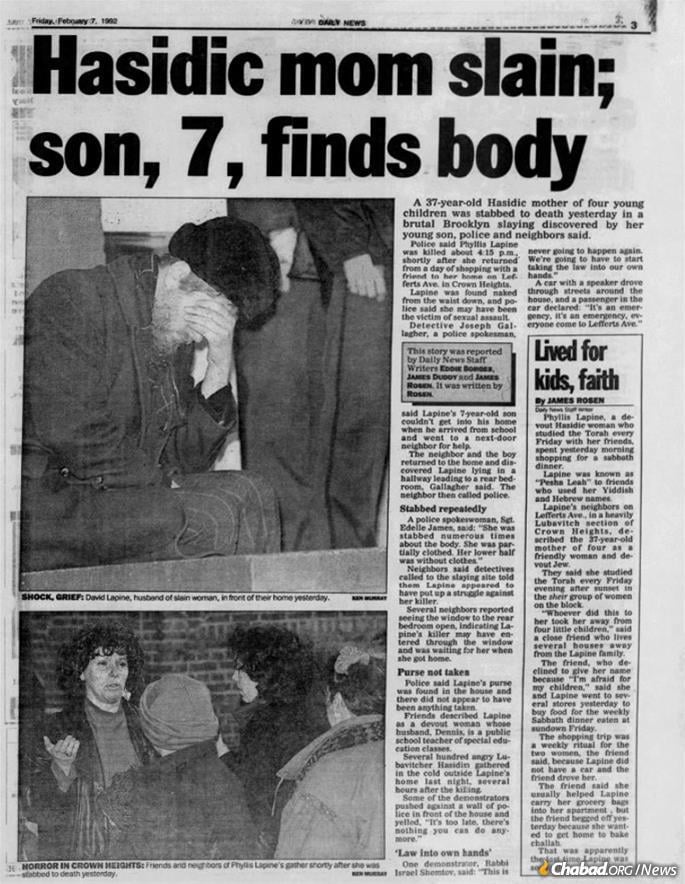

The horrific murder of Pesha Leah Lapine shocked the Crown Heights Jewish community and the city of New York at large. The Brooklyn assistant district attorney on the case called it “the most heinous crime in recent years in this county.”

At the end of the seven day shiva mourning period, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—spoke publicly about Lapine’s life and sacrifice. The murder of a young mother, one who had transformed her life to grow as a Jew and given so much to raise her family in a vibrant Jewish community, could only be understood in the context of Jewish sacrifice through the ages.

“What has occurred—an act of martyrdom—is utterly incomprehensible! There is no one to whom to turn for an explanation,” he cried out. “All those present, including myself, are equally confounded. So what do we gain by questioning? The question still remains … !”

The Rebbe spoke about the fact that Lapine’s young children would long for their mother, and one day tell their own children about their holy grandmother who had sanctified G‑d’s name.

With the Rebbe’s words still reverberating in his mind all these years later, on the 30th anniversary of his mother’s murder, Rabbi Lapine started a new project in his mother’s memory. The campaign to build the Columbia Jewish community’s first mikvah began in February 2022, and when complete it will be the only one for nearly 150 miles in either direction. Lapine, who has a daughter and nieces named after his mother, hopes that the mikvah will perpetuate the dedication to Judaism that his mother personified.

Small-Town Texas Judaism

Pesha Leah Levin, or Phyliss as she was then known, was born on July 30, 1953, the 19th of the Jewish month of Av, in El Campo, Texas, a small agricultural town in the floodplains of the Colorado River about an hour’s drive south of Houston. Her parents, Frank and Betty Levin, were one of only a half dozen Jewish families in the town of 7,000.

They were traditional, at least by El Campo standards, making annual trips to Frank’s family 80 miles north in Brenham for the Passover Seders and closing the family’s drive-through grocery store every Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

“We went to Shabbat services Friday nights,” recalls Marilyn Duchan, Lapine’s older sister by four years. “But in small-town Texas, football is king.” Shabbat services, held in the synagogue in nearby Wharton, took place year-round at 8 p.m., only after the varsity game had ended.

Despite such unorthodoxies, the Levins were proud of their Judaism. “Growing up, Mother always taught us, ‘If you practice your religion and show you’re proud of who you are, people will respect you,’ ” says Duchan.

Today, Duchan describes the sort of idyllic 1960s all-American life that she and her sister grew up with. They enjoyed trips to the drive-in, ice-cream floats at the soda shop and weekend-long barbecues from the family’s backyard smoke pit.

At El Campo High School, Phyliss was part of the National Honor Society and an avid member of the debate team. Her classmate Martha Chappell would later tell The New York Times that Phyliss was so engrossed in her debate prep that she often neglected more mundane matters. “Someone would be assigned to roll up [her] sleeves before she began her debate.”

Phyliss was accepted to the University of Texas in Austin, where she graduated with a degree in communications in 1975. By then “it was clear to me that Phyliss was looking for something,” says Duchan. “For a community, for meaning.”

Following a summer trip to visit family at a large kibbutz in Israel and a stint pursuing a master’s degree at Hebrew University, Phyliss went to visit the Western Wall in Jerusalem. A chance invitation there to attend a communal Shabbat meal opened new horizons in Jewish practice to Phyliss. After taking some occasional classes in Jerusalem, she enrolled in the Neve Yerushalayim seminary and spent the year in Jewish study. When she returned to Texas at the end of the year, Phyliss had taken to using her Jewish name, Pesha Leah.

Settling back in at home in El Campo as a newly observant Jew had its challenges.

“My mother was ready to send her on the first flight back to Israel when she landed,” recounts Duchan. An aborted attempt to make the family barbecue pit kosher had less than happy results. “Father, who grew up in an Orthodox home, would not have his daughter tell him how to properly barbecue a brisket.”

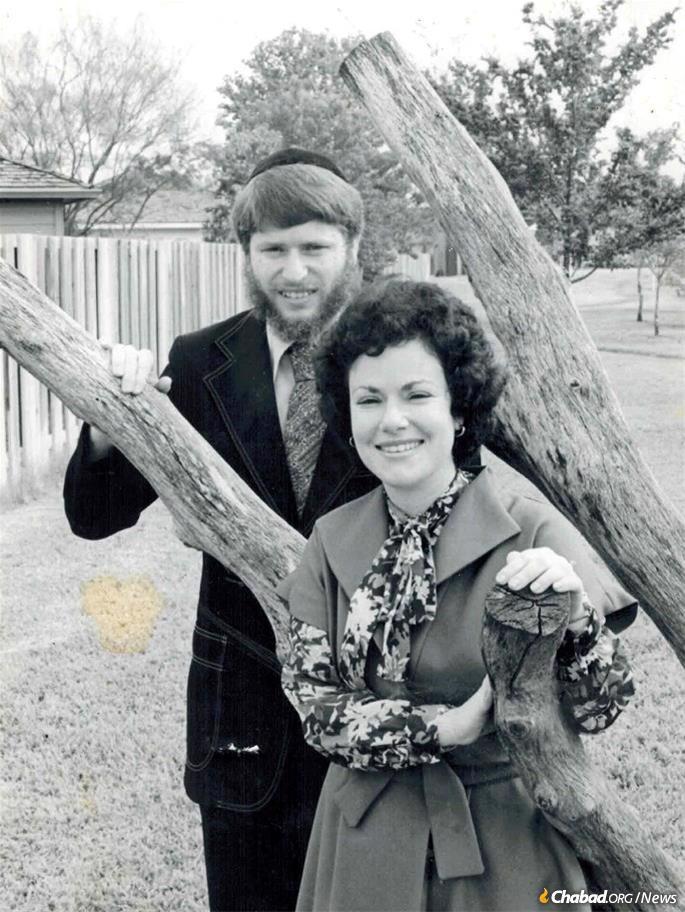

Pesha Leah began spending time in Houston’s Orthodox community, where friends introduced her to Chaim Dovid (Dennis) Lapine. Born in Houston and raised in Kansas, Chaim Dovid Lapine had grown religious through Chabad-Lubavitch in Kansas City and returned to Texas to work in the family grocery store. He and Pesha Leah hit it off, and after taking full advantage of Houston’s kosher dating scene (namely, long conversations while eating kosher candy in the parking lot of a 7-Eleven), were soon engaged.

A Chassidic Wedding in Wharton

When time came for choosing a wedding venue, the Levins insisted that Pesha Leah and Chaim Dovid marry at the family synagogue in Wharton. The chuppah and ensuing wedding—held outside the star-shaped synagogue building in February 1979 and officiated by Chabad of Texas director Rabbi Shimon Lazaroff and Chabad of Kansas City director Rabbi Sholom Ber Wineberg—were a sight to behold: a full Chassidic wedding in small-town Texas. For the celebration, they even managed to make sure the synagogue’s communal barbecue pit was freshly koshered so that Frank Levin could serve a glatt-kosher brisket to guests.

After the wedding, the Lapines lived in Houston before moving to Morristown, N.J. When Pesha Leah was offered a job working for the Anti-Defamation League in 1984, the Lapines moved to New York City. The young couple thought there was no better place to settle than Crown Heights in Brooklyn. With access to synagogues and spiritual life, and the chance to regularly learn from the Rebbe, it was a place of vibrant opportunity.

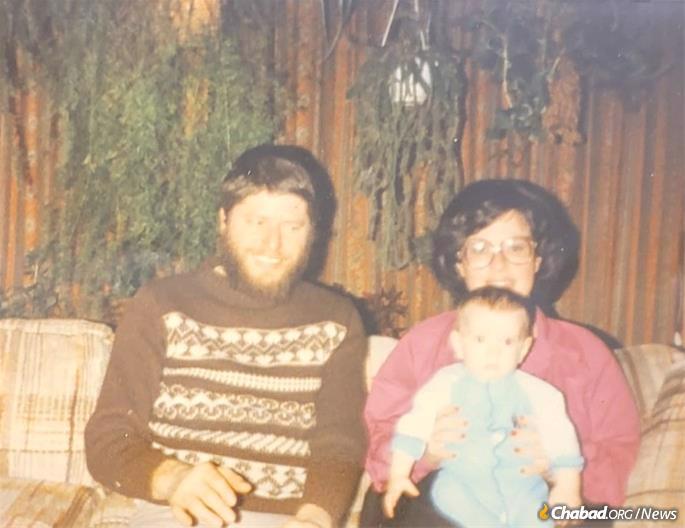

One point was particularly painful for the Lapines. After more than four years of marriage, they still didn’t have any children. A year after arriving in Crown Heights, after countless hours spent with specialists and a key blessing from the Rebbe, the Lapines were finally blessed with Faivel, the first of their four children.

Pesha Leah’s joy seemed complete.

“After so many years of waiting, of praying, when we finally had a child, she really just embraced being a mother, being there for our children,” says Chaim Dovid Lapine. “That’s what she wanted to do.”

Chaim Dovid got a job as a special-education teacher for the New York City public school system, and as the family grew, the Lapines moved to the house on Lefferts Avenue.

Life, however, was far from easy in Crown Heights in the 1980s. Crime was high and the neighborhood, like the rest of Brooklyn, was starved for resources. The Lubavitcher community, the sole Jewish community not to abandon the neighborhood during the explosion of crime and subsequent community flight of the proceeding decades, remained tenaciously in place.

In August 1991, after the bloody, antisemitic Crown Heights riots swept through the neighborhood, Chaim Dovid remembers a phone call from his father. “Are you sure you want to stay there?” asked the elder Lapine.

The Lapines, however, would hear nothing of leaving their community. Social and outgoing, they took part in neighborhood Torah classes, hosted Shabbat guests and shared widely with others. Pesha Leah was particularly keen on helping young Jewish women who had recently moved to the Jewish community, especially alumni from her beloved Neve seminary.

“If Pesha Leah found out someone went to Neve,” Chaim Dovid recalls, “she’d invite them over for the next Shabbat.”

In the summer of 1991, she even managed to host a Texas-style barbecue with other guests in the bungalow colonies in the Catskills.

Fractured Memories

“I remember that Thursday, I put up the challah dough very late—it must have been right around 2 p.m. that I left it to rise,” recalls Feige Jacobson, who lived down the block from the Lapine family. She and Pesha Leah used to shop for Shabbat together in Borough Park. Not merely shopping trips, the afternoon drives were transformed with conversation, sharing recipes and Jewish life lessons. On that February day, however, the trip was unusually rushed.

“So I got the challah up late,” Jacobson recalls, emotionally rushing her words. “It was very late. So in addition to shopping with Pesha Leah, I needed to pick up food for my father, who lived in Borough Park, and then we needed to be back in time for Pesha Leah to pick up her baby from daycare.”

The two women, overburdened with packages from shopping, returned to Crown Heights. Pulling up in front of Lapine’s home, it was then that Jacobson realized her rising challah dough might be overflowing.

“So I looked at Pesha Leah,” Jacobson says. “We both had a lot of groceries and I asked, ‘Do you mind if I just bring your packages to the porch’–because I wanted to help her–‘and then I’m going to take care of my challah?’ ”

Jacobson helped Lapine to the porch and then rushed home. It was sometime after 3 p.m.

Unbeknown to the two women, across the street was Romane LaFond, a 24-year-old unemployed handyman who loitered about the neighborhood. Mentally ill and with a criminal record, LaFond had a history of stalking and assaulting Chassidic women. As Lapine made the first of several trips to bring her daughter and the groceries in, LaFond followed them in and locked the front door.

Jewish Blood Is Not Cheap

“I remember looking through the window into the house,” says Avraham Lapine. “Pulling myself down, I told the neighbor, ‘I think I see someone lying on the floor?’ ”

The neighbor made a face that Avraham, only five, couldn’t parse, and then walked him to her house.

Word spread quickly on the block. Hearing the sirens, Feige Jacobson ran over to the Lapine residence. There she overheard a female detective describing the scene to a colleague.

“I began to scream,” Jacobson recalls. “This was a nightmare; you hear about these kinds of things in the news, but how could it be happening? Later, in court, we heard how bad it was … But also how she fought back against that malach hamavos (‘angel of death’), that achzar (‘sadist’). She fought him with everything she had.”

Shortly afterwards, Chaim Dovid Lapine returned from work.

“You come home and see the police everywhere,” he says. “You try to think ‘Maybe it’s not my family? Maybe it’s not so bad?’ Then, when you realize what’s really happened, it’s this terrible shock.”

Police officers and detectives streamed in and out of the house, the groceries still sitting on the porch. Unsure of what else to do, numb with grief, Lapine took a book of Tehillim from his pocket and began to read.

The pain in Crown Heights was palpable. The trauma of the previous decades coupled with the sense that the city had turned a blind eye on a violent, antisemitic riots, brought hundreds to the street. As Chassidim marched to the 71st Precinct station to demand protection, non-Jewish neighbors rained rocks, flowerpots and bottles down on the Jews, who shouted back. Later that evening, two non-Jewish men beat and robbed a Jewish couple walking home from an unrelated gathering.

Police officers in riot gear filled the streets and reporters rushed in with cameras, all under the impression that the Chassidim in Crown Heights would riot in retaliation for the pain of the violence.

The crowd swelled. An elderly Jewish man fell, apparently hit in the head by a police officer’s nightstick. At one point, a Caribbean-American teenager climbed onto a Jewish-owned bus, hoisting a sign made by a Chassidic protester above his head, its words screaming out to the words: “Jewish Blood Is Not Cheap.”

“I kind of want to represent the black community and tell them I’m with them, not against them,” he told The New York Times. “I hate to see this happen to the Hasidic people.”

Dawn broke on Friday morning with the frenzied predictions unfulfilled, but the true sign of Jewish anguish was yet to come.

Pesha Leah’s family, the Levins, received a call from New York and flew in from El Campo for the funeral. In a daze, Marilyn Duchan recalls only the biting cold and being picked up by “New York’s Finest,” the NYPD, at the airport for their escort to the funeral. They were followed by a cluster of reporters hoping to better understand the loss of Pesha Leah.

“We just kind of went through the motions,” says Duchan. “When something like that happens, burying a child in such a way, it takes a toll on the parents. They’re never the same.”

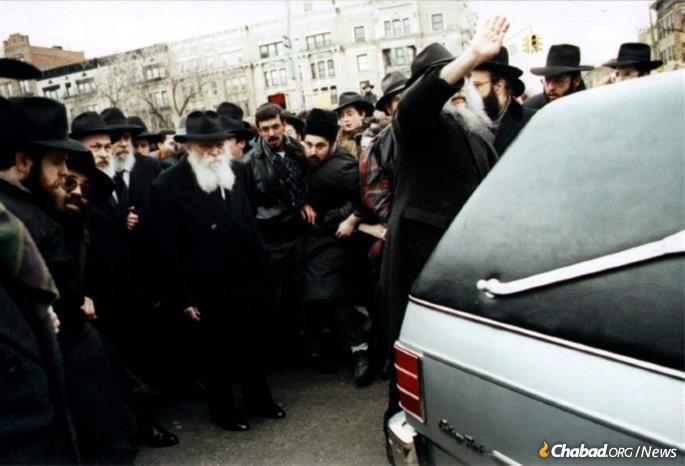

Some 4,000 mourners filled the streets of Crown Heights for the funeral. The Rebbe himself took part, following the hearse down the block as the funeral procession made its way from Chabad World Headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway to the Lapine home and then on to Queens for the burial.

As thousands of mourners streamed past, the Rebbe paused under a large banner stretching across the street that said “Moshiach is on his way.” Stopping for a moment, the Rebbe looked up, his eyes turned heavenward as the stream of humanity poured forth around him.

A week later, at the conclusion of Lapine’s shiva, the Rebbe spoke in 770. Though directly addressing those gathered in the synagogue, the Rebbe’s words seemed more clearly directed at G‑d Himself.

“What do we gain if we have questions and no answers seem apparent? When it seems, Heaven spare us, that the redemption is being delayed ever further?” the Rebbe asked.

Drawing a lesson from generations of Jewish sacrifice and how precious those Jews are, he continued. “G‑d may hold dear the preciousness of a Jew’s self-sacrifice—but there’s been enough sacrifice over the course of this exile—an exile that has spanned nineteen hundred years, and Moshiach is still not here! One day passes to the next, one week leads to another… How much longer will this exile continue? We cry out, we beg and beseech G‑d, ‘It’s enough!’ and what is the result? A mother is taken away from her children… a greater self-sacrifice than any other! May G‑d answer us already, and save us from having to ask more questions, to have more difficulties, more sacrifices!”

‘Legacy of Someone Taken Away So Young’

Less than a week after Lapine’s murder, LaFond was arrested after tips came in from Jews and non-Jews in Crown Heights.

Community members had recalled seeing him around the neighborhood. Pesha Leah’s cousin, who had been in town to visit several weeks prior, realized LaFond had come to the house, barging in to offer his services as a handyman.

“Oh, what a horrible year that was,” Jacobson recalls. “We were all back and forth between the courtrooms. Between the trial for the murder for Pesha Leah and the trial for the murder of Yankel Rosenbaum, the Australian student researching antisemitism who’d been murdered during the riots, it felt like every man and woman in Crown Heights was there.”

The community stepped in to help the Lapine children. Feige Jacobson’s sister-in-law and another Lefferts Avenue neighbor, Feigel Jacobson and others helped the Lapines.

Quiet and reserved, Feigel reflects on the intervening years. “Sometimes, I wonder,” she says. “We were so focused on making sure their day-to-day needs were met, did we help them with their trauma?”

Duchan feels a similar void looking at her sister’s murder.

“It’s hard to reflect on the legacy for someone who was taken away from us so young,” she says. “The future? That’s for her children.”

Avraham has drawn lessons from his painful memories, but hopes the mikvah will serve a broader purpose, connecting Jews to their heritage and epitomizing everything his mother believed in.

The pain that gnaws at the heart of all who knew Pesha Leah remains, but as the Rebbe reflected, the legacy of Jewish growth abides.

“ … [T]hese children will long for their mother,” he said in February 1992. “They will recount to their own children their intense longing for their mother; they will tell them that she merited to sanctify G‑d’s Name. … The Redemption should come immediately. … And then this young woman will meet her children and continue their education with a joyous heart.”

To support the Mikvah Mei Pesya Leah Lapine project in Columbia, Mo., click here