Why critics of the Iran deal should hope Obama is like Neville Chamberlain

Published July 14, 2015

British statesman and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain at Heston Airport on his return from Munich after meeting with Hitler, making his “peace in our time” address. (Central Press/Getty Images)

It was just a few weeks after the Sept. 11 attacks and suddenly U.S.-Israel tensions were erupting. The White House was furious at Prime Minister Ariel Sharon for essentially comparing President George W. Bush’s efforts to line up Arab support for his war on terror to Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement.

“Don’t repeat the terrible mistake of 1938 when the enlightened democracies of Europe decided to sacrifice Czechoslovakia for a temporary solution. Do not try to placate the Arabs at our expense,” Sharon defiantly declared. “Israel will not be Czechoslovakia.”

READ: Netanyahu: Iran deal a ‘stunning historic mistake’

As it happened, shortly after Sharon’s remarks, his predecessor, Ehud Barak, was making an appearance at a fundraising gala at a posh hotel in midtown Manhattan. When buttonholed by this reporter for a response, Barak expressed a measure of sympathy for Sharon’s concerns, but criticized the appeasement reference. Barak insisted that such talk was off the mark and out of place at a time when British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Bush were playing the respective roles of Churchill and Roosevelt in forging a global alliance against al-Qaida and terrorism.

In retrospect, that controversy turned out to be a blip. It didn’t take long for Sharon to change his tune and race to align Israel’s diplomatic and security strategies with the Bush administration’s agenda on most fronts.

READ: The text of the Iran deal

Now, with the ink still wet on the U.S.-backed deal with Iran, it’s hard to imagine a similar rapprochement for Barack Obama and Benjamin Netanyahu.

U.S. President Barack Obama departs the White House July 14, 2015, in Washington, D.C. (Win McNamee/Getty Images)

If Sharon’s Czechoslovakia comment was an outburst, Netanyahu’s condemnations of the Iran deal have been a drumbeat, with repeated warnings that the world powers were on course to sign an agreement that would effectively appease Tehran’s long-term nuclear ambitions and pose a genocidal threat to Israel.

The deal might be done, but Netanyahu isn’t backing down.

“The international community is removing the sanctions, and Iran is keeping its nuclear program,” Netanyahu said at a news conference Tuesday, referencing an earlier statement by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani. “By not dismantling Iran’s nuclear program, in a decade this deal will give an unreformed, unrepentant and far richer terrorist regime the capacity to develop many nuclear bombs.”

Nonsense, say Obama and his aides, insisting that this deal is in fact the most likely way (short of war) to keep Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons.

READ: Spoilers alert: Six guys to watch the day after an Iran deal

It’s not surprising that the argument taking center stage is the one over which path (if any) will stop Tehran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons in the long run. But this raging debate is obscuring the more pressing question of whether the spoils of this deal will end up fueling Iranian aggression throughout the region.

In this regard, Obama is no Neville Chamberlain: The president and his aides have not promised a peaceful Iran in our time — just no Iranian nukes. Even while arguing that this deal is the best bet on the nuclear front, they acknowledge that Iran’s support for violent anti-Israel, anti-American and anti-Sunni proxies will likely continue, and possibly increase. To help allay fears of longtime U.S. allies, including Israel and Saudi Arabia, the Obama administration has been attempting to hand hold while approving increased arms sales.

READ: Obama: Nuclear deal cuts off pathway to Iranian bomb

The problem is that serious doubts persist in the region over whether the Obama administration will stand up if Iran does not stand down.

Ironically, now that there is a deal, these worried allies could do a lot worse than Neville Chamberlain. While the British prime minister seems destined to be forever ridiculed for naively believing Hitler could be satiated, often forgotten or ignored is what came next. Once Germany’s invasion of Poland made clear his colossal misjudgment, Chamberlain did not run away from his mistake. He took England to war and then, in order to secure the formation of a unity government, eventually stepped down to make way for Churchill and became a member of the War Cabinet.

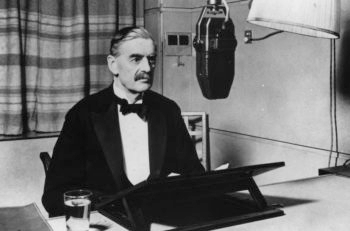

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in a BBC studio announcing the declaration of war, Sept. 3, 1939. (Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Sounding downright Churchillian, Chamberlain announced his resignation in a broadcast to the British nation with the following plea: “For the hour has now come when we are to be put to the test, as the innocent people of Holland, Belgium and France are being tested already. And you and I must rally behind our new leader, and with our united strength, and with unshakable courage fight, and work until this wild beast, which has sprung out of his lair upon us, has been finally disarmed and overthrown.”

History may prove Obama right that his agreement is no Munich Conference-style abandonment of Israel on the nuclear issue. But if Iran converts its newfound diplomatic and economic gains into increased military aggression, then Churchill’s warning will apply just the same: “Do not suppose that this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning.”

And, in that case, the immediate question won’t be if there are Iranian nukes in our time, but whether in the face of continued aggression from an emboldened Iran the president is prepared to be a Roosevelt or Churchill — or, at the very least, a Chamberlain.![]()