When I cried with Leah Rabin, the ‘lioness’ of Israel

Published November 4, 2015

And then I got the call. Vogue magazine assigned me an exclusive interview with Leah Rabin. It would be an in-depth profile, a five-page spread dedicated to the Rabin legacy and the woman who was left behind to carry it.

When I stood at the base of the Rabin residence before walking into her home I was terrified. This was not just a story — it was the story. The world was watching, awaiting Leah’s response.

ADVERTISEMENT

Following the assassination, Leah became known as the “lioness” of Israel, mothering a nation whose dreams of peace had been shattered. In her deepest pain, she was taking care of us. She knew she had to carry her husband’s heavy torch.

As an American reporter and a newbie in Jerusalem, I felt the weight of the world on my shoulders. I must have checked my tape recorder 15 times, brought my backup recorder, packed enough batteries to start a car. I actually rehearsed my questions aloud.

When Leah greeted me in her home, it took everything I had not to cry on the spot. But as the interview progressed, we had our moment. I asked her the one question that I was terrified to ask: “Does he talk to you when you’re alone? Is he proud of you?”

ADVERTISEMENT

This stoic woman looked at me, grabbed my hand inside hers and began to cry. And I cried, too. There was no journalist-subject separation, just two women consoling one another. I knew that she and I would stay connected.

And we did.

Leah would send me annual notes, usually well wishes around Rosh Hashanah, and my heart would skip a beat whenever I would see the familiar powder blue envelope in my mailbox. When she passed away in 2000 at the age of 72 , I felt a deep loss.

This interview, this moment in time, affected me in many ways. I named my firstborn Noa in honor of Leah’s beautiful red-headed granddaughter. The way I approach my work — my journalism, my books — is always with the same care and sensitivity with which I connected with Leah Rabin. I not only have to report a story, I have to feel it deeply before I can write it.

In my 25 years as a journalist, I have covered a lot of ground — including the famous Clinton-Rabin-Arafat “handshake” on the White House Lawn — but none, before or after, have ever compared to that precious time shared in Leah’s living room.

Her story and her 47-year marriage with Yitzhak Rabin touched me deeply. His greatness was her greatness; his failings weighed upon her. His peace became her peace. His death became her calling to carry his legacy.

Time has passed. She has passed. But this interview, when the tape recorder was turned on and Leah Rabin opened up, still resonates. I’m proud to republish it on JTA today, of all days, commemorating 20 years since Yitzhak Rabin’s life was abruptly cut short.

***

I stand on the sidewalk gazing at the bland, beige eight-story apartment building before me. It blends easily into the Bauhaus-influenced mosaic of concrete cubes dotting the affluent Tel Aviv neighborhood. Through the glass panes I see a smattering of potted plants inside the foyer—nice, clean, but nothing fancy. Let’s face it, I think, this is not the kind of place where one imagines a prime minister living. It’s too ordinary—basic, like a flat-topped Lego construct.

Looking around, I’m struck by the eerie suburban quiet. For weeks on end in November, hordes of citizens — from all walks of life — joined hands and surrounded the building with memorial candles, flowers, poetry, and song, creating a tearful fortress. “Two bullets killed this great man,” Leah Rabin had told the hundreds of people who gathered beneath her home to convey their condolences just before the funeral. “It’s a pity that you all weren’t here when there were demonstrators calling him a traitor and a murderer. But you are here now, and that encourages me. I value this and love you in his name.”

I ring the door buzzer, upon which is printed in Hebrew simply RABIN, along with 32 other family names. A security guard leads me up to an eighth-floor apartment. I walk in but suddenly stop in my tracks. It’s him. Yitzhak Rabin, in 2-D everywhere. A shrine of large and small portraits fills the walls and crevices, dominating the room. Hanging over a large-screen TV, which serves as a shelf for the Nobel Peace Prize, is an assortment of caricatures — mostly from his army days with the ever-present cigarette dangling from his lips. The images overshadow the lovely furniture, the eclectic art collection, and the hundreds of well-traveled knickknacks.

Leah enters, hand outstretched graciously, smile ready-made. She wears Laura Petrie-style slim black pants (I should only have legs like hers when I’m 68), a cream-colored scoop-necked sweater, and layers of her signature gold chains and bangles. Hers is a powerfully lived-in face, unabashedly well lined, forming different plateaus with each expression. We sit across from each other, coffee in hand, with just enough emotional distance: Leah Rabin is nobody’s victim.

“Everybody asks me about my strength. I don’t know where it comes from. Living with Yitzhak for 47 years has rubbed off on me,” she says with a wan smile. “I suppose what affected me most was what happened to the people of this country. Nothing like an assassination has ever occurred here before; there was no precedent to this kind of tragedy. There has been the most profound grief among the people. They didn’t talk to me about my pain; they talked of their pain and looked to me to help them get through it,” she says. “It was as if the nation lost their father, grandfather. I had to pick up the pieces. There was no time to think. But it’s getting to me lately. The accumulation of all this pain. I’m not so strong. I’m crying a lot.” Leah’s voice cracks; the tears stream easily now.

“Does he talk to you when you’re alone? Is he proud of you?” I ask softly.

“Is he proud?” She looks up toward the ceiling. “Yes. I try to do everything that would make him proud. But I think if he saw me crying now, he would say, ‘That’s not like you, Leah.’”

But it is. It is the face she has shown the public throughout her ordeal. Leah Rabin’s strength is her open pain — never masking her emotions, grieving whenever and wherever it hits her.

Leah recounts the events of Nov. 4 with slow, measured words, lowering her voice to almost a whisper. It was a beautiful night, perfect weather for the 100,000 Israelis attending the pro-peace, anti-violence rally held in the heart of Tel Aviv, since renamed Yitzhak Rabin Square. The furor and excitement were contagious — the antithesis of the climate of political rage that had prevailed for so many months.

The country had been deeply divided since the day Yitzhak Rabin shook hands with his longtime enemy Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat on the White House lawn in 1993 and signed an agreement that recognized the Palestine Liberation Organization and set a timetable for the peace process. After “the handshake,” Palestinian terrorists launched a series of devastating bus bombings that claimed scores of Israeli lives. Infuriated, Israelis who opposed the peace process took to the streets daily, shouting epithets and torching portraits of Rabin.

Leah explained how the day before her husband’s assassination, a large group of right-wing protesters surrounded her apartment, as they had every Friday, screaming “Traitor! We will do the same to you and your husband as was done to Mussolini and his mistress!”

“I suffered terribly from all the hatred,” Leah recalls. “But not Yitzhak. He accepted things in a way other people couldn’t. He endured all of that as part of the process. I often asked him, ‘Do you even know how much the people love and respect you?’ The peace rally was a symbol of his achievement. He felt the outpouring of unity and affection. That thought gives me comfort now.”

When her husband finished his speech and the rally ended, Leah followed him down a back staircase to the waiting car, and then the shots rang out. “I still see that moment before my eyes all the time. It doesn’t leave me for a minute. The sight of my husband walking down the stairs and falling. Who would have thought that the killer would be a Jew? Even with all the demonstrations, it never entered our minds.” She shakes her head in disbelief.

When I ask if the 27-year-old assassin, Yigal Amir, a third-year law student and reserve soldier for an elite army unit, deserves the death penalty, an uncomfortable silence fills the room. Leah’s green eyes flicker bitterly; her voice sounds cold. “I don’t relate to him as a human being whatsoever. For me he doesn’t exist.” Her voice becomes shrill. “And the way the media give his family so much attention is appalling. It shouldn’t be allowed. We are doing everything to fight it.”

When the assassin’s mother made a televised plea to the Rabin family asking for forgiveness, Leah ignored her, dismissing the incident with a swift wrist flick: “I didn’t watch it; I’m not interested in him or his family.”

Quickly, she switches gears to the final moments she spent with her husband in the hospital. She stayed with him two hours after he died. In the hospital she said, “Why wasn’t it me and not him? Who am I?”

***

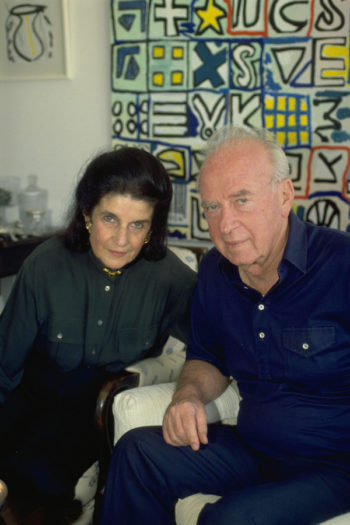

Leah and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1992. (Israel Government Press Office)

Leah Rabin isn’t easily categorized, though she has always been distinctively herself. She was born Leah Schlossberg in Germany in 1928. Twenty years later she married Yitzhak Rabin, a rising military leader who played an important role in Israel’s fight for independence. They had two children — a daughter, Dalia, in 1951, and a son, Yuval, five years later. In 1967, shortly after Rabin helped secure a stunning military victory in Israel’s Six-Day War, he decided to leave the battlefield after 27 years of soldiering and start working toward peace. He knew that the place to do it from was Washington, D.C., home of the power brokers.

Yitzhak did the politicking as Israel’s ambassador to the United States, and Leah was known for her classy dinner parties. The duo was extremely popular in Washington society. “Those were five wonderful years,” Leah says. “An unforgettable learning experience. The transition wasn’t hard. Yitzhak loved every moment. OK, so he didn’t like the cocktail parties as much as being in Washington,” she admits, giggling at some faraway thought. “But we made good friends, the Kissingers and others with whom we have remained close to this day.”

It was during that time that the Israeli media dubbed Leah “the Middle East’s answer to Jackie Kennedy Onassis.” With her rich black mane, dark, round starlet sunglasses, Mediterranean good looks, elegant clothes, and high-profile friends, Leah was a trendsetter — the other half of Israel’s “renaissance couple.” While her husband was the shy, rugged “sabra” (native-born Israeli), militarily brilliant and known as “Mr. Security,” Leah was his flamboyant counterpart.

Donnie Radcliffe, who has covered the capital’s social scene for 28 years for The Washington Star and The Washington Post, described the Rabins as a social force in Washington — but an unusual one. “They were not the kind of people to engage in traditional small talk; they seemed to have no patience for Washington banalities,” she says. “Leah was always very focused. She was extremely attractive, well respected, had a terrific sense of style, and was always a proper hostess. She played her role well, did her job, but unlike many diplomats’ wives, she was not particularly ambitious in the sense of being a ‘pace-setting hostess.’ ”

The distinctive style that was evident in Washington more than two decades ago still endures. Oscar de la Renta, a close friend of Leah’s for many years, says of Israel’s first lady, “I love her look. She has a wonderful, strong face. I don’t think she spends a lot of time worrying about how she dresses — she’s naturally elegant. She always knows what she wants immediately. She’s extremely sure of herself as an individual, and it reflects in her taste.”

Though Leah and Jackie O were both known for their exacting taste, there was one critical distinction between them: their mouths. Leah tells it like it is, and always has. She is known for being opinionated, sharp-tongued, and outspoken, while Jackie thrived on quiet, stiff-upper-lipped privacy.

Leah has always been considered an Israeli anomaly, in the early years, in contrast to the wives of her husband’s fellow officers and later when she moved among the Stepford-like spouses of her husband’s political contacts. Her independent and at times enigmatic persona created tension with the Israeli media. “Over the years, the media have been very tough on us,” Leah said, pursing her lips. “Were you aware of the pin story?” Of course I was. Everyone read about it at the time.

The story went something like this: Leah lost her brooch during the signing of Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan in 1994, and she sent an entire army platoon on its hands and knees to find it. “The truth of the matter is that all I did was approach a security guard and say, ‘If someone returns a pin, it’s mine, I lost it.’ End of story. Then the media got wind of it and blew it up maliciously. Maybe they like seeing me miserable. An entire platoon? Please. Who ever heard of such a thing?”

I remind her of the media’s love affair with her since the assassination. “Yes, that’s true,” she admits, then adds, with a raised eyebrow, “For now.”

“Leah’s had a difficult relationship with the press because she has always taken a position on all kinds of issues,” says Arlene Strelitz, her close friend of 25 years. “She’s extremely frank and very decisive. She was the first political spouse to do this — to be vocal and visible.”

If Washington was a peak, then returning home brought the Rabins some time in the valley. In 1977, the Israeli press discovered Leah’s illegal United States bank account, left open from the couple’s Washington sojourn. Leah was charged with possessing foreign currency (the charge sheet presented by the Tel Aviv district attorney listed the sum, including interest, at $21,101) without having offered to sell it to the Treasury, which was required by law. The headlines were cruel and unforgiving. Leah pleaded guilty and accepted what was then considered a steep fine of 250,000 Israeli lirot (approximately $27,000). She was forced to apologize publicly. The Israeli reaction was mixed. Some felt that Leah had already been punished enough by the media and that the fine was too severe. Others were angry at the country’s first couple, who should have been setting an example for the nation. The timing of the offense couldn’t have been worse — coming right before an election — and contributed to her husband’s resignation as prime minister and to the eventual fall of his Labor Party.

“Yitzhak was as strong as a rock during such moments. He stood by me fully,” she says quietly. “It was then that our partnership shined. He never let me feel like I was alone.”

One time that Leah stood solo on the world’s stage was in 1975, when she headed the Israeli delegation to the World Conference on Women in Mexico City. At the time, Israel was considered a pariah by many nations, and appearing at the conference was a sensitive political undertaking on Leah’s part. She knew she would be facing many of Israel’s adversaries at the conference, including Jihan Sadat, wife of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, who then was considered an enemy of the Jewish state (but who later made peace with Israel). At the conference Jihan had said, “If women were making the peace, it would have been done a long time ago.”

“Baloney!” Leah shouts as I recall those words. “That conference was the most abusive situation I’ve ever encountered. It was not an arena for peace. When it was my turn to speak, two-thirds of all the women present got up and walked out. I said how sad it was that women are continuing to be manipulated by men and their parties. We came to make a better future for our children, and what do we see? Just more hatred and abuse. Our delegation felt so much bitterness, isolation, and loneliness. I was shaken by what we were facing.

“But times have changed,” she says, quickly shifting into a brighter mood. “Today Suha Arafat called me. And a few days ago Queen Noor telephoned just to see how I was doing. The peace process has transformed everything. I was with my husband at the United Nations’ 50th-anniversary celebration [last October], and we were among the most popular there. My husband had 40 meetings with heads of state in two days. Everyone wanted to be near him, us. We walked around feeling the wonderful achievement of the peace process and how it has changed our position in the world.”

Though Leah speaks with heated passion about the potential for peace, she is known for her coolness under pressure, her sense of propriety, and her fastidious attention to detail — even at her husband’s funeral. When Jordan’s King Hussein and Queen Noor paid a condolence call, it was a matter of protocol to serve refreshments. But when a waitress offered Leah a drink before anyone else, she reportedly reprimanded the young woman in Hebrew, “Serve the king first.”

A tireless fundraiser, Leah sits on the boards of several major charities and takes enormous pride in her “baby” — Alut, the Israeli Association for Autistic Children, which she has served as president for 22 years. This month she will come to New York City to host an event for Israel’s Sheba Medical Center. In May Leah organized one of Israel’s splashiest charitable affairs. Oscar de la Renta held a highly publicized fashion extravaganza in an El Al hangar at Ben Gurion Airport on behalf of Sheba.

“I have never done a show like that before,” de la Renta recalls. “The models came out of the plane onto a runway. It was spectacular.” Of the function, Leah says, “That was wonderful. We raised a lot of money. Everyone came that night.”

And then she adds, with a sigh, that as busy as her husband was, he always made time to appear at all of her events.

***

“What does Leah say?” became the national mantra during the first month after the assassination. When Leah called on a beleaguered nation to allow Shimon Peres, Yitzhak Rabin’s longtime political foe and recent peace partner, to carry on her husband’s policies, her wish was granted. Peres was chosen with near-unanimous support to serve out Prime Minister Rabin’s term.

Political sharks — wasting no time during an election year — were determined to capitalize on Leah’s huge public following and sent the rumor mill into high gear. Leah Rabin for Knesset (Israel’s parliament) … future prime minister … ambassador to the United States … president of Israel.

Her daughter, Dalia, with whom she is extremely close, even said on Israeli television that her mother would make an excellent politician, heightening speculation.

But Leah puts her hands out like a stop sign. “Look, I see myself as Yitzhak’s partner. I shared my life with him, his achievements. If I go into politics, I will have to struggle to prove myself. People will not accept me just because I was his wife. They will expect me to deliver. Why should I put myself in that position? To be a member of the Knesset? Big deal. I would like to carry on my life and do my utmost to honor my husband and children.”

Yet Leah’s words continue to draw thunder. Immediately after the funeral she pointed an accusatory finger at the opposition Likud Party and right-wing factions, blaming them for having created the violent political climate in which her husband was murdered. Critics lashed back, holding Leah responsible for further dividing a country that so badly needed to heal.

But shaking her head, she says firmly, “It is not my destiny to unite the people. It’s the religious leaders who should do something about it. The ball’s in their court now, not mine. They should oust those irresponsible people who are ready to kill, to whom land is more sacred than a human life. They don’t belong to our faith and should be kicked out immediately.”

Leah’s ire doesn’t stop there. When I mention how she took on Ted Koppel, the vaunted host of “Nightline,” when he broadcast a segment from Jerusalem following the assassination, she lashes out angrily. “That was an absolute horror show,” she recalls. “It was pre-orchestrated to support the Likud and its leader, Bibi [Benjamin] Netanyahu. Ted Koppel can say 10 times that it wasn’t, but 80 percent of the audience was against the peace. Earlier when I spoke to Ted and told him, ‘What we are witnessing here is something astounding, unprecedented — the sight of thousands of people lighting candles and visiting my husband’s grave, uniting in song.’ He just looked at me and said, ‘That will all pass in a couple of weeks. But how come you shook Yasser Arafat’s hand in your home and did not shake Bibi’s?’ By the way, I did shake Bibi’s hand. But I could sense right there that Ted Koppel just didn’t want to understand what was going on here. He came here with a preconception.” Koppel declined to comment on Leah’s allegation.

I ask whether the peace is moving too fast for people. Leah blurts out a response before I can complete my sentence. “No. I trusted my husband. He did things slowly and meticulously. He didn’t consult me on his policies, but if I questioned something, he always explained his reasons and convinced me. He believed, as I do, that an agreement should be anchored in a reality we can live with.”

After the funeral, at an exhaustive pace, Leah traveled from memorial to memorial, from country to country — Washington, D.C., New York, Paris, even the Vatican, where she met with Pope John Paul II — spreading her husband’s message of reconciliation. Though she is comfortable as a roving ambassador of peace, there are those on both sides of the political spectrum who would like to muzzle what they describe as her “political outbursts.”

One such outburst occurred recently. Just before Israeli negotiators were to meet with Syrian officials last December in Maryland, Leah called on Syrian President Hafez Assad to jump on the peace train. Some Israeli politicians were angry at what they thought was a poorly timed public prodding that could hurt the sensitive negotiations. “People have warned me that I must watch what I say,” she says. But the look in her eyes declares otherwise. No one tells Leah Rabin what to do.

***

Yitzhak Rabin once described his romance with Leah as “a glance, a word, a stirring within, and then a further meeting.” It was 1944. He was 22; she was 16.

“The first moment I laid eyes on him, I felt something. He was very handsome. I kept seeing him around. I thought he must be in the Palmach [the volunteer prestate defense force]. You see, in high school all the girls were in love with Palmach soldiers. They had this romantic, aura about them. I asked around, ‘Who is that guy?’ Someone said, ‘He’s Yitzhak Rabin; he’s special.’ I said to myself, ‘Let’s see how special he is.’ And now I ask myself over and over again, ‘How did I know, at 16 years old, to pick the best one?’”

Leah says perhaps it is because she inherited her father’s excellent instinct. Her family escaped Nazi Germany when she was 5. Her father had said that if Adolf Hitler came to power, his family would leave the next day. And sure enough, the day after Hitler was elected chancellor, the Schlossberg family packed up, taking with them only their personal belongings — a move that saved their lives. They boarded a boat to Israel and never looked back. Leah herself joined the Palmach, serving in the battalion in which Rabin was the deputy commander. There she learned how to throw grenades and shoot a rifle. In his memoirs, Yitzhak Rabin wrote jokingly, “It was the only time she was under my command.”

“When I think back to the early years, I remember how Yitzhak and I immediately understood that each of us needed to accept the other’s differences. We knew what was important. But you see,” she adds, barely audible, “it’s the little things I miss the most. Our tennis matches every Saturday. Our breakfasts every morning at 7. I always got up and never let him make his own coffee. Never!” she says with the protective fierceness of a lioness.

“On household matters, I was the one to make the decisions. We agreed this was my domain. He would ask me to pick out ties for him. I always gave him a choice of two; I let it be his decision. Now I cannot even look at his ties, can’t look at them. I tell you here in this house, I have not touched anything. Everything is in place as if tomorrow morning he will be here again.

“I am so busy, and the kids never let me spend one night alone,” she continues. “I am trying to plow through the tens of thousands of letters I still haven’t answered. It’s very frustrating because I’ve always answered every letter myself. I’m also working on my memoir. It will be different from my first book, ‘Full-Time Wife.’ This book will reflect on the recent years, cover the aftermath of the murder, and share with Yitzhak everything that has happened — all that we’ve lived through.”

After the assassination, Leah was besieged by literary agents from Israel, Europe, and the United States vying to handle the rights to her story. She settled on Robert Barnett, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who represents capital heavyweights like Dan Quayle, James Carville, and William Bennett. Unconfirmed reports in the Israeli press say that a seven-figure deal is in the works for her memoirs.

Leah is not the only member of the Rabin family writing her story. A month after the funeral, Leah’s 18-year-old granddaughter, Noa Ben-Artzi Filosof, whose heartwrenching eulogy at her grandfather’s funeral captivated the world, signed a book deal with Alfred A. Knopf, allegedly for $1 million. The 200-page book, due out next month, will be an autobiography and a plea for peace in the Middle East.

Noa’s advance drew some heat in the Israeli press. But defending what some critics termed a “commercialization of Yitzhak Rabin’s’ murder,” Noa’s older brother, Yonaton, 21, told the Hebrew newspaper Yerushalayim that “since she was a little girl, Noa has always expressed her feelings through writing. If Noa’s future will be enhanced by writing this book, my grandfather would have been the first to support her.”

As for Leah, she says she will spend the rest of her life making sure her husband’s death was not in vain, that the assassination did not kill his dream.

“You know,” she says, sipping the last remnants of her coffee, “for 47 years we shared the most difficult moments, so each of us had only half the hardship to carry. And now that the most horrible thing happened, I have to carry it all alone.”

(Lisa Barr is the Chicago-based author of the award-winning historical novel “Fugitive Colors.”)