The ‘queer, disabled’ Zionist who challenged the conventions of Israel’s founders

Published May 22, 2022

(JTA) — It’s hard to find a poster promoting early 20th-century Zionism that doesn’t depict a tanned, chiseled man toting a shovel or a gun. The posters were visual reinforcement of the “Muscle Jewry” valued by Max Nordau and other early Zionist leaders, who felt the land would redeem a physically depleted Jewish people and the people would renew a neglected land.

One early Zionist thinker defied this macho image, and then some: “While Zionism celebrated strong and healthy bodies,” Jessie Sampter “spoke of herself as ‘crippled’ from polio and plagued by weakness and sickness her whole life.” In addition, “she wrote of homoerotic longings and had same-sex relationships we would consider queer.”

Those quotes are from Sarah Imhoff’s new biography, “The Lives of Jessie Sampter: Queer, Disabled, Zionist” (Duke University Press). The book explores the life of a New York-born poet and writer ((1883–1938) who moved to Palestine in 1919 and whose circle before and after included Henrietta Szold, who founded Hadassah; Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism; Louis Brandeis, the future U.S. Supreme Court justice and leader of the Zionist Organization of America; the writer Mary Antin, and Albert Einstein.

ADVERTISEMENT

Although Sampter never became a household name, she published 11 books and dozens of poems in English and Hebrew. She shared a home at Kibbutz Givat Brenner with the Russian Zionist Leah Berlin, and advocated on behalf of Yemenite Jews and the pre-state Jewish community’s deaf population. She never married nor bore children, although she did adopt a Yemenite Jewish daughter. Her story is worth remembering, writes Imhoff, because Sampter’s life itself represented an alternative vision of Zionism — one that “did not follow the gender norms prescribed for the ideal (male) Zionist builder or the female Zionist nurturer of the nation.”

Imhoff is associate professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, and author of “Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism.” We spoke via Zoom on Thursday.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

New York Jewish Week: I had never heard of Jessie Sampter. When did you come to know her and decide she was a subject to be written about?

ADVERTISEMENT

Sarah Imhoff: My first book was about masculinity and American Judaism. I had plenty of men talking about Zionism and masculinity, and I was wondering what women, specifically American Jewish women, thought about Zionism and masculinity. I knew that Sampter was a Zionist, so I got hold of some of her files in Jerusalem. She didn’t actually have that much to say about masculinity and Zionism, but I was totally captivated

Before we get to her Zionism, let’s place her in New York, the kind of family she was born into and the way she grew up.

She was born in Harlem. She grew up with two parents who were German Jewish and fairly middle class. They belonged to the Ethical Culture movement with other acculturated Jews. They spoke English at home, they had a Christmas tree at home, at least sometimes. They’re integrated into what I think of as a Jewish culture.

Even though they didn’t ascribe to Judaism itself.

Jessie has this story about when she was perhaps 8 years old. Somebody said, “You’re a Jew!” And she replied, “No, I’m not!” and went home crying. And then her parents told her, “Well, actually, we are Jewish,” but it doesn’t seem like that was a major way they talked about themselves.

And as she grew up she became what we might call a seeker — exploring Eastern religions, seances, Transcendentalism, Ouija boards — but what you prefer to describe in terms of “religious recombination.”

I like that as a metaphor, because it suggests that what you end up with is actually a whole thing, rather than what some refer to as a “cafeteria religion,” which can be a little condescending. When people think about “how do I understand the world” they draw on things that we could trace to different religious traditions. She doesn’t go “religion hopping,” but has this early life of being very interested in religion, but not knowing where she fits. And then, interestingly, she comes to Zionism before she comes to Judaism, which is a relatively unusual thing.

Tell me a little bit more about that. How old is she at that point?

She is definitely there by 1914, so her mid-to-late 20s. Many people at that moment are thinking about nationalism, and not necessarily in the way that we think about nationalism. We might say “peoplehood.” One of the things she likes about Zionism is it imagines Jews as a people the way Mordecai Kaplan did, and she and Kaplan are often in contact.

She thinks that Jews as a people have something distinctive to contribute to the project of humanity. She would also say that every people has something distinctive to contribute to the project of humanity, but part of our goal is to figure out what that is, and each people can be its own people and then we’ll all be stronger together. And then she thinks, well, if part of what the Jewish people has to offer is a biblical tradition, or prophetic tradition, I should explore Judaism.

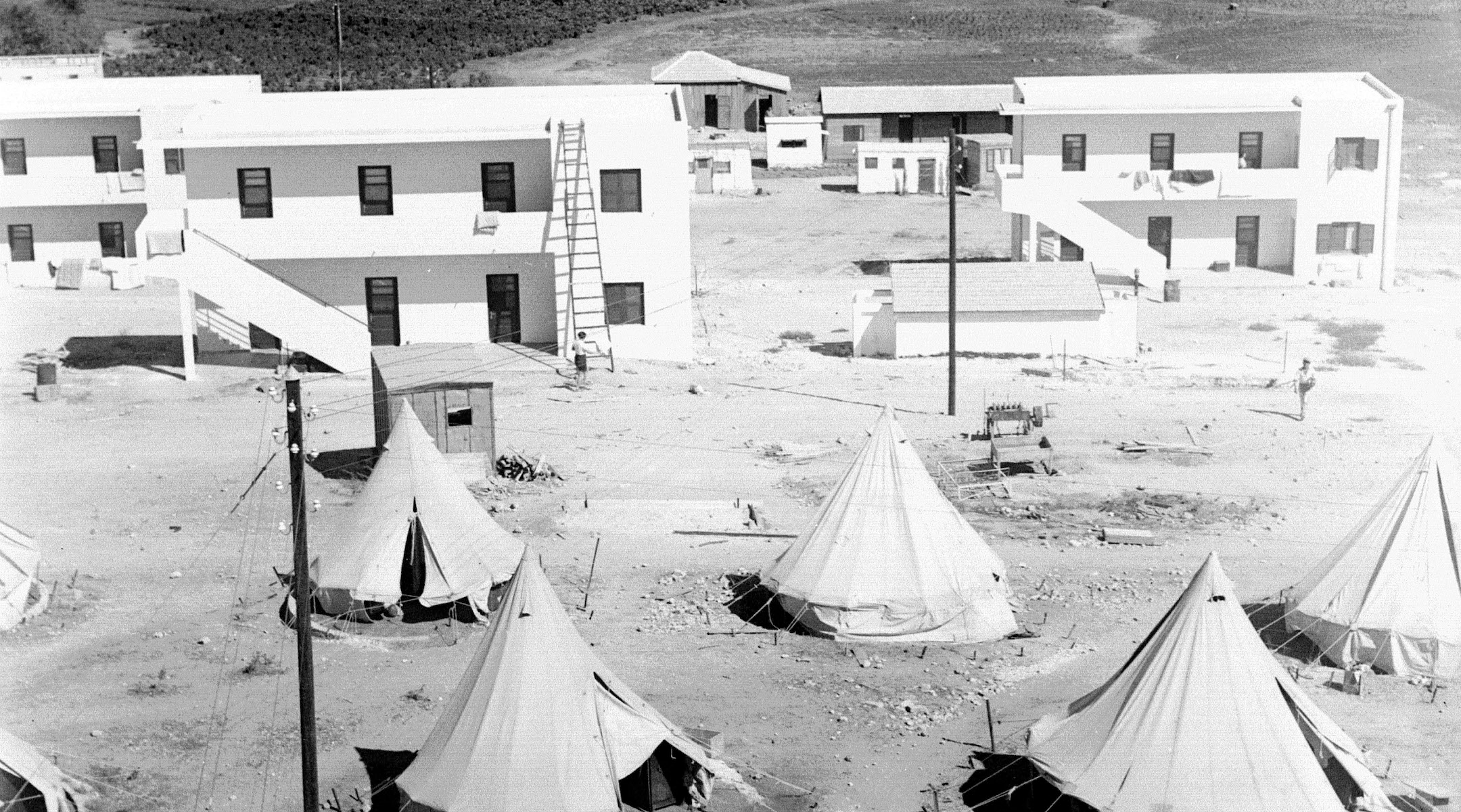

Jessie Sampter lived at Kibbutz Givat Brenner, shown above in 1935, until her death in 1938. (Israel Government Press Office)

And yet, she’s a single woman in the early 20th century, when not a lot of Americans were willing to sail across the world and become a pioneer in a kind of backwater country. Where does she get the impulse?

That’s a great question. A Zionist friend of hers, Lotta Levensohn, calls its a “malarial swamp.” Sampter was trying to convince the Zionist Organization of America to send her and initially they said no, but eventually she convinced Brandeis. That’s how she narrates it, anyway. And she goes on a one-year contract where she’ll be writing and they’ll be paying her to write, and even when she goes she is thinking that staying is her plan. She writes that she is “getting married” to Palestine. I think it is audacious, especially because she’s disabled with what I think is post-polio syndrome. Basically right after she lands she ends up in Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem for a few weeks recuperating.

She got polio when she was 12. Describe her disability and how she presented physically either to others or to herself.

If you see a photo of her it’s not obvious, although she’s often holding her own wrist or putting her hands behind her back. There are no action shots of her; she’s almost always sitting in a chair or posed standing still. If you just looked at her at one instant, you wouldn’t see disability. But if you interacted with her at any length, you probably would.

And she definitely had limitations in terms of walking, or working with her hands, and while she loved working in her garden there were limits on what she could do.

Right. And those are things that are much more pressing in Palestine than they are in New York.

And that’s because the pioneers were expected to work and build the homeland with their hands and backs as “muscle Jews.”

That idea permeates a lot of Jewish settlement in Palestine at that time. She’s involved a little bit in the scouting movement, which is about making little muscle Jews: “We’re gonna go hiking, you’re gonna learn to build the nation.” That permeates almost all of the Zionist propaganda that you can see in the U.S. and in Europe, too.

And is she very much aware that she’s in a contradiction with the classic Zionism of the day?

Yes, she is. There are moments when I see her in her writing pushing against it. She’s involved with early deaf education in Palestine, and she thinks deaf people can grow up to be real, central citizens when others didn’t. She’s involved in Yemenite education, too. She insists on a democratic approach that says the Yemenite housewife is the same as the male European halutz [pioneer], and she says — and these would be my words — that we want a more inclusive Zionism with respect to bodies.

But she has a lot of self doubt. There are moments where she’s very cognizant of not fitting in and, maybe in that moment, buys into the Zionist ideal of healthy, strong bodies.

If her physical limitations set her apart, I imagine her sexual identity would too. This is also in a community where procreation is considered a Zionist tenet.

I’ve wrestled with this a lot. I wouldn’t say she has a clear identity. I wouldn’t, for example, call her lesbian, because she wouldn’t have self-described that way. There are two things that I think make it right to think about her in queer terms. Her father died when she was young, her mother died not long after. And she created what queer theorists often think of as a chosen family. She met Leah Berlin very soon after moving to Palestine, and the two of them live together most of the time. They lived apart for a little bit and then they moved back in together and made financial decisions, like to go to Kibbutz Givat Brenner together. She adopted a Yemenite orphan named Tamar. And Leah would visit Tamar when she was a little older and away at school.

It’s not like she has no biological family — she writes a ton of letters to her sister Elvie — but there are these kinship structures that look very much like chosen family and they’re queer kinship structures.

I have no idea if she ever had sex with Leah Berlin. But it’s not common for women of the time to write about sex acts, period. But she expresses what I call queer desire, whether fantasizing being married to a girl playmate or always wanting to be the soldier when she was playing. There are erotic ways that she describes a friendship with another woman.

How was she seen in Palestine or on the kibbutz? Perhaps as a “spinster,” or was her relationship with Leah Berlin understood as something else and just sort of tolerated?

When she’s thinking about joining the kibbutz, it’s clear that it’s double or nothing: They get the pair of them or they get no one. They’re coming together.

You referenced Tamar, the Yemenite toddler that she adopts. How unusual was that? And I think we should say this is not in the 1950s, when the Ashkenazi elite was separating Yemenite kids from their birth parents.

It’s not that, but there is still an undergirding of cultural assumptions about Ashkenazi culture being more civilized or better than Yemenite culture. This was not part of that same story, but it obviously has connections. But Sampter was involved in Yemenite education, like setting up a Yemenite kindergarten, so she really cared about Yemenite kids and women.

Adopting a Yemenite child was relatively unusual. Some of her friends think it’s a terrible idea. Even Henrietta Szold says, “How are you going to take care of this kid? You can barely take care of yourself.”

Speaking of Henrietta Szold, in 1915 Sampter writes a sort of Zionist textbook for Hadassah, “Course in Zionism.” Tell me about her relationship with Szold and the women’s Zionist movement.

Her relationship with Szold began before that textbook, going back to something like 1910 or 1911. Sempter looks up to Szold and Szold also recognizes something in Sampter. They try having her be a speaker for Hadassah and I think for reasons related to her disability that just doesn’t fly. I’m also not sure Sampter was very charismatic. She might have in fact been a kind of difficult person. But pretty early on in her own Zionist development she is writing for Hadassah. Sampter thinks of Szold as a mentor, and even tries out being a little bit more Orthodox, but then kind of backs off a little bit later.

She died in 1938, 10 years before statehood, but already the armed struggle against the Arabs and the British in charge of Palestine had begun. You write that she was a pacifist who supported Jewish armed defense in Palestine.

She bought a gun at one point. She was like, “I have no idea how to shoot it, but I’m gonna put it here in case somebody needs to come in and use it.” She’s a pacifist except that she believes that sometimes we might need to defend ourselves. Her position moves back and forth. She experiences some of the armed conflict in Palestine, although it’s clear she thinks the real bad guys are the British, who she thinks are setting up Jews and Arabs to fight it out for resources and land.

She has moments of being more interested and understanding of Arabs than some of her contemporaries. And then she also has moments of saying that the Arabs have more to learn from Jews than Jews have to learn from them. It’s not quite as one sided as it is for many others. On the other hand, it is clear which side has her basic loyalty.

She had a number of well-known friends, but again, she’s hardly as well known today as they are. What about her body of work might still be valuable or worth knowing about today?

What’s compelling is a little bit about her body of work and a little bit about her own story. She makes us think about the real variety of possibilities for Zionism. I think, today, Zionism has a much narrower set of meanings than it did in Sampter’s time. She gestures toward other possibilities.

Give me an example. How did she broaden the definition of Zionism?

I think the disability example, which includes both her own life and what she wrote, shows us that there are ways of imagining society that don’t have to privilege an able-bodied, frankly male vision of society. Also, “Mizrahi” wasn’t functional at that time, but her Zionism does really try to think about how the Yemenite Jews and Moroccan Jews fit into it. The Zionist vision that prevailed in Israel was an Ashkenazi one. Her example could be a resource for people who might want to imagine the contemporary state of Israel in different ways.

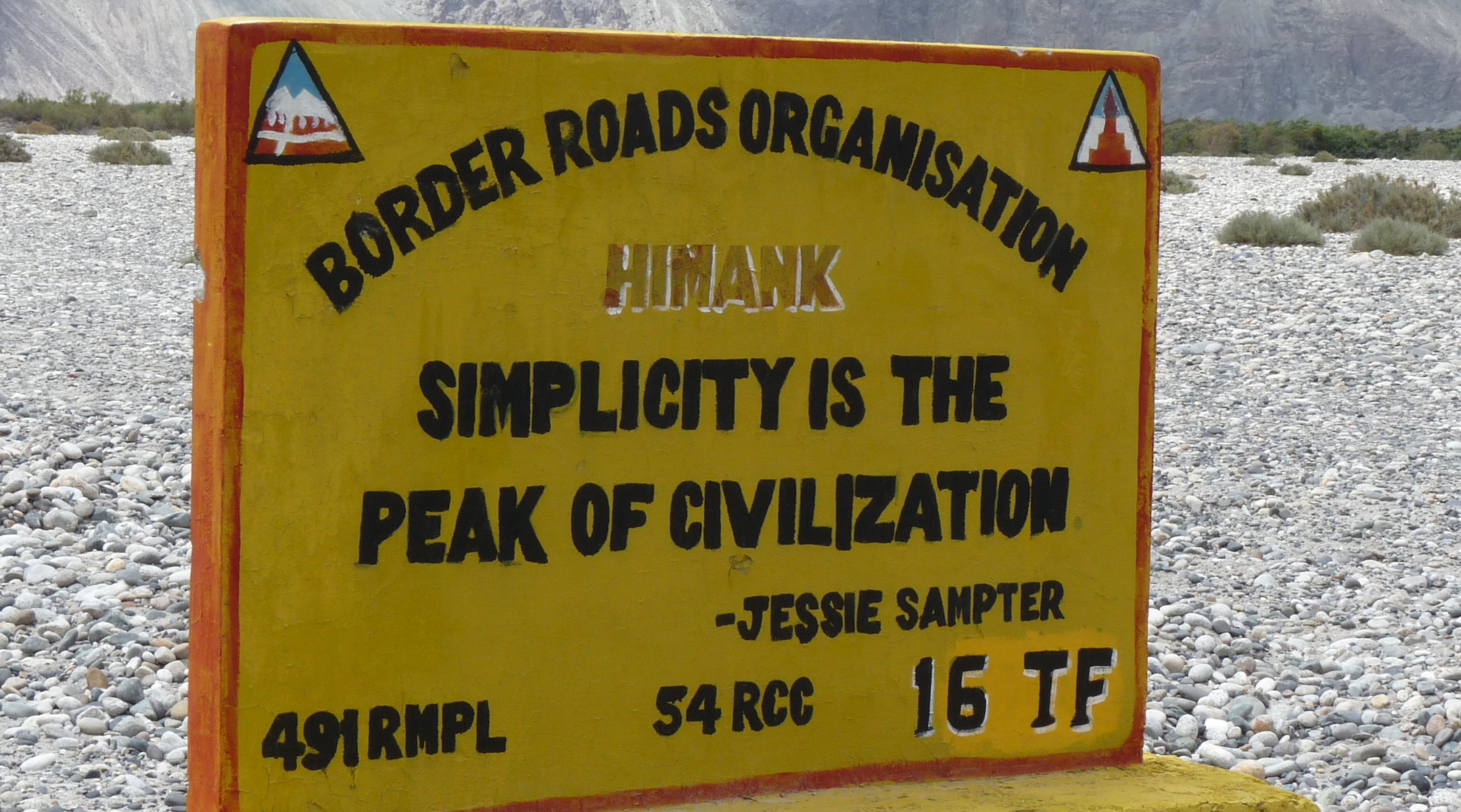

One of Jessie Sampter’s quotes, taken from one of her poems and popularized in a book of quotations by women, appears on a sign in Ladakh, India. (Wikipedia)

You write that after she died Sampter became a “quotable philosopher, appearing in Weight Watchers inspirational books, on websites and on a roadside in India.” What sort of quotes appealed to pop culture?

Most of those are actually the same quote, which is “simplicity is the peak of civilization,” which is weirdly in the middle of a poem. So I thought that’s kind of strange. How did Weight Watchers get this thing? I traced it back to a rabbi who was doing a collection of quotes of Jewish women. I did in fact go hunting for the road sign in India. I think the internet plays a role in why so many picked up that one quote.

How else do we access her today? Are any of her books in print? Is there a monument to her?

Some folks at Givat Brenner still remember her and still tell stories about her. The rest house she helped found is still standing, although it is no longer a rest house. I don’t know if any of her books are in print. She’s not very well remembered. I think there are reasons for that. I think her being single is actually one of them. It’s often families that are good at memorializing and publicizing the importance of people. And I think it’s because her Zionism was not actually the Zionism that got picked up as the mainstream. She doesn’t fit what people imagine that group of pioneers to be.

My argument in the book is not that “here’s this really influential woman we’ve forgotten.” It’s almost, “look, this woman wrote all of these things, and was really well connected, and wasn’t influential. But she shows us these roads not taken.”

—

The post The ‘queer, disabled’ Zionist who challenged the conventions of Israel’s founders appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.