Op-Ed: Protesters of Israeli musicians are singing wrong tune

Published February 1, 2015

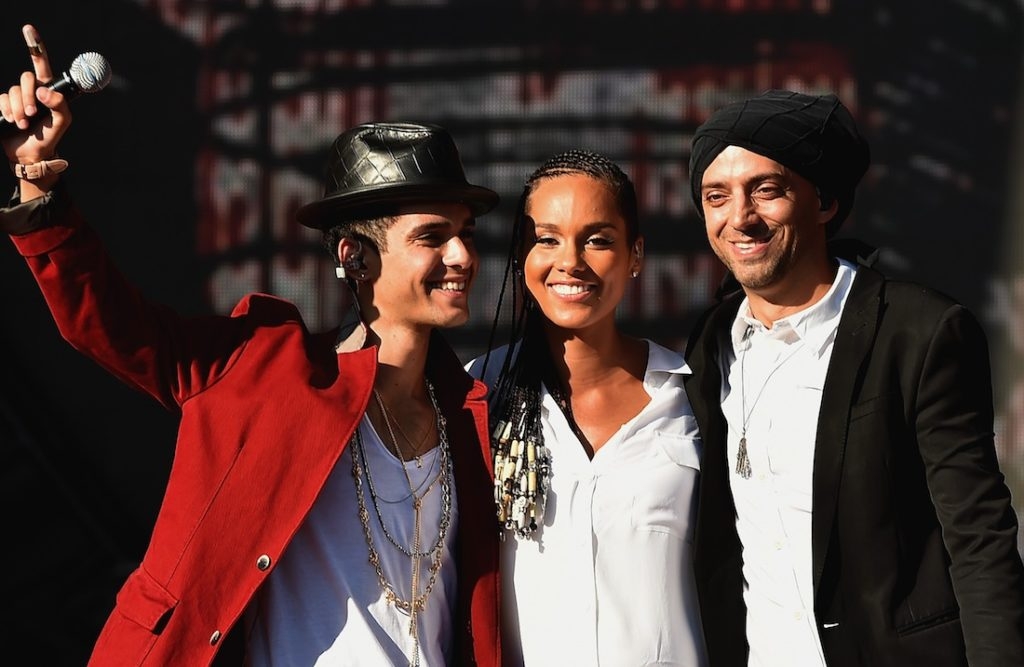

Palestinian musician Ali Amir-Kanoon, left, Israeli artist Idan Raichel, right, and American Alicia Keys performing at the 2014 Global Citizen Festival in New York, Sept. 27, 2014. (Theo Wargo/Getty Images for Global Citizen Festival)

ADVERTISEMENT

(JTA) — On a fall evening in 2014, more than 70,000 people gathered in New York’s Central Park for the U.N.-sponsored Global Citizen Festival. Another 3.6 million watched on national television as Alicia Keys, Israeli musician Idan Raichel and Palestinian artist Ali Amr sang “We Are Here” and called for peace and reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians.

The act showcased Raichel’s musical collaborations with various world artists, which helped him win MTV’s 2014 Role Model Award. At other times, however, human rights activists have protested Raichel’s performances, calling him “a self-proclaimed propagandist for the Israeli government.”

Disturbingly, such protests seem to be common these days. Palestinian sympathizers take their fight against Israel to concert and dance halls across the world in an effort to disrupt Israeli artists at work. While high demand for tickets has not soured, it is clear that performing Israeli artists are under attack.

Israeli artists in all areas represent the most liberal sounds in Israeli society, advocating for peace, understanding and bridging the divides between torn peoples. Raichel and many of his fellow Israeli artists work closely with their Palestinian and Arab-Israeli counterparts. Achinoam Nini, best known as Noa, is a well-known peace advocate who has performed with Arab-Israeli singer Mira Awad. Israeli superstar singer David Broza has been singing about peace and collaborating with Palestinian musicians since 1977. His recent “East Jerusalem West Jerusalem” album was recorded in Sabreen, a Palestinian recording studio in eastern Jerusalem, and featured Israeli, Palestinian and American musicians.

The Israeli dance companies Batsheva and Vertigo work with Arab dancers and dance groups and are influenced by Arab dance and music. Batsheva runs programs that reach Jewish, Christian and Muslim youngsters. Still, the two companies faced protesters during recent U.S. tours.

Arab tunes and movements are evident in much of the work of Israeli musicians and dancers. And Israeli movies and plays often give voice to multiple narratives, both Israeli and Palestinians, forcing us to see the other in a new way.

Art comes from the heart, touches the heart and plays a critical role in improving our communication and bringing people closer together. It allows us to see perspectives that we might otherwise resist and can influence our thinking.

Those who protest Israeli artists are choosing the wrong targets. They are demonstrating against the very voices within Israeli society that reach out to the Palestinian people and call for others to do so as well. They are protesting against those who represent what unites people from both sides of the divide.

These folks are singing the wrong tune.

(Sarit Arbell, the former cultural attache at Israel’s Washington embassy, is founder of Israel on Stage, a nonprofit that showcases Israeli artists.)

![]()