With services online, many synagogues are seeing greater attendance — at least for now

Published April 20, 2020

(JTA) — Mike Finesilver started attending daily services for the first time since his bar mitzvah shortly after joining Congregation Beth El in 2012.

Praying every day with the same small group of people was “a wonderful experience” for the 62-year-old paralegal, and he enjoyed being deeply involved with the Conservative synagogue in South Orange, New Jersey.

But when he accepted a job a few years later that required a commute to New York, attending the daily minyan, or prayer group, was no longer feasible.

“My life went back into the stress of getting up, getting on the bus, commuting. There was no kind of spiritual foundation there,” he said.

That changed last month when Congregation Beth El started livestreaming all its activities rather than holding them in person to decrease the risk of spreading the coronavirus. Now Finesilver, whose commute disappeared after his office also closed because of the pandemic, is praying again each morning with the tight-knit minyan.

“This global pandemic is terrifying, really, so to have some kind of spiritual anchor is a real gift,” Finesilver said.

He’s not the only one at Beth El making it to morning services more often. A service that typically drew 15-20 worshippers prior to the coronavirus outbreak now has some 30 computers logging on daily. Since multiple family members often watch from one screen, that sometimes means as many as 50 people are tuning in.

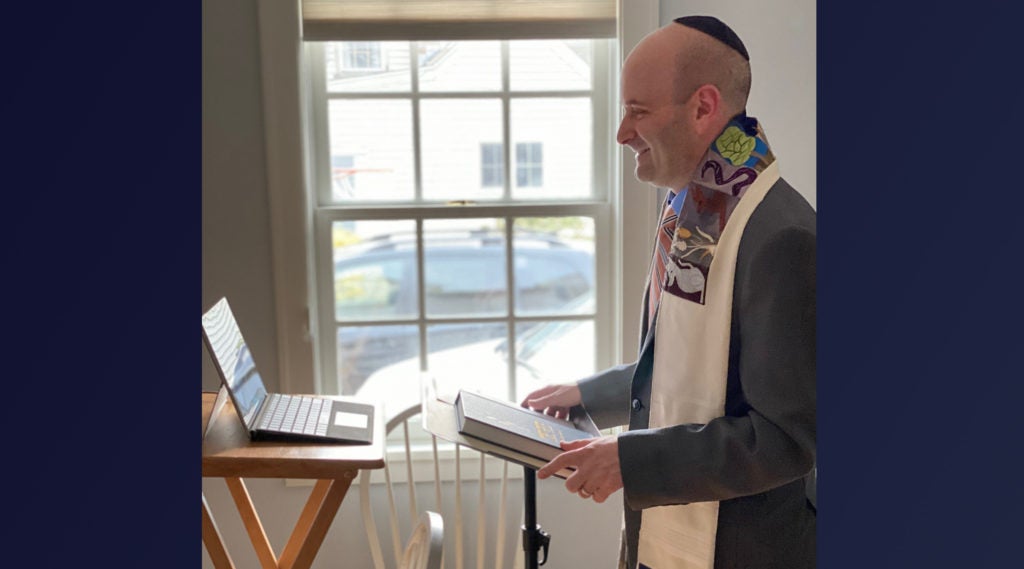

“It’s been an eye-opening experience for us, understanding how many of those who have joined previously were unable to join,” Rabbi Jesse Olitzky said.

Beth El’s experience is playing out in many parts of the Jewish world. As synagogues have moved services online, rabbis say they are seeing a surge in attendance because of the increased accessibility and Jews seeking solace amid the deadly pandemic.

Indeed, people often seek out religious services during difficult times, according to Rabbi Eliezer Schnall, a professor of clinical psychology at Yeshiva University who researches the relationship between mental health and religion.

“This is a time of uncertainty, whether because of the pandemic or the related economic meltdown. People are reaching out for stability,” he said.

But Schnall said it’s not just a hunger for stability that might be causing congregants to log on to virtual services.

“There’s the fact that people are nervous, the fact that people are scared and they hunger for something like religion to grasp onto,” he said. “There’s the social element that people are lonely, there’s the technological component that this is something we can do today in ways that are easier than ever before.

“There’s also the lack of whatever else I would be doing.”

Indeed, most non-Orthodox synagogues have long competed for congregants’ time and attention, with work, competitive sports or school activities sometimes proving more attractive than worship services. But with the coronavirus pandemic upending — and often just ending — those options, congregants have fewer built-in ways to experience community.

Meanwhile, the situation is different in Orthodox communities. On a typical weekday, the Young Israel of Woodmere, an Orthodox congregation on Long Island with 1,300 member families, holds 10 morning services that attract a total of 500-600 worshippers. The same number come for their afternoon/evening ones.

The synagogue has been holding weekday services over Zoom but with a much lower attendance — about 20-30 people attends its morning service and up to 100 join the afternoon and evening ones. (Like other Orthodox synagogues, the Young Israel of Woodmere does not offer any virtual services during Shabbat.)

Part of that has to do with the fact that unlike many Reform and Conservative synagogues, Orthodox ones do not allow for a virtual minyan, the prayer quorum of 10 that is necessary to say certain prayers, including the Mourner’s Kaddish.

“I think a lot of people might feel, ‘I’m not praying in a minyan anyway, I’m not going to be locked into a specific time on Zoom, I can just do my prayers at home,’” Rabbi Hershel Billet said.

Some non-Orthodox synagogues are responding to the increased interest by adding services. Temple Shir Tikva, a Reform congregation with 575 member families in Wayland, Massachusetts, typically drew 100 people in person to its Friday night service before the coronavirus, and another 20 would join by livestream.

But now that services have been getting more than 600 views combined through its website, Facebook and YouTube, the synagogue also launched a weekly Havdalah service to mark the conclusion of Shabbat.

“People are looking for spiritual connection at this time and the synagogue community, the religious community in general, I think is becoming more and more important for people to feel that sense of connectedness in the world when everyone is in their own home,” Rabbi Danny Burkeman said.

Temple Rodef Shalom, a Reform synagogue with nearly 1,800 member families in Falls Church, Virginia, typically gets about 250-350 worshippers at its regular Shabbat services. Though some virtual services since the pandemic have seen a fewer number, some have been much higher, gaining more than 500 views.

The synagogue had been livestreaming its services prior to the coronavirus, but it recently started streaming on Facebook in addition to its website and has been getting approximately 500 additional views there. The majority who join are members, but there are non-members, too.

Rabbi Amy Schwartzman said she isn’t sure if the higher attendance is here to stay — but of course hopes it is. She has seen similar spikes during other difficult times, including when her synagogue was picketed by the Westboro Baptist Church, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and following the shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue.

“When this all finishes — who knows when that will be — and when we go back to our regular scheduled lives, while I do think the temple will take better advantage of technology and other people may as well, I think for a large part we will go back to the usual” in terms of attendance, she said.

Still, Schwartzman said the high level of interest has caused her to think about how else she can use technology to engage the community.

“I do think that this experience will change us for the better in so many ways,” she said. “One of them, I think, is that congregations, including my own, will learn and embrace technology in greater depth.”