Why more Orthodox Jews are going to AIPAC

Published March 5, 2018

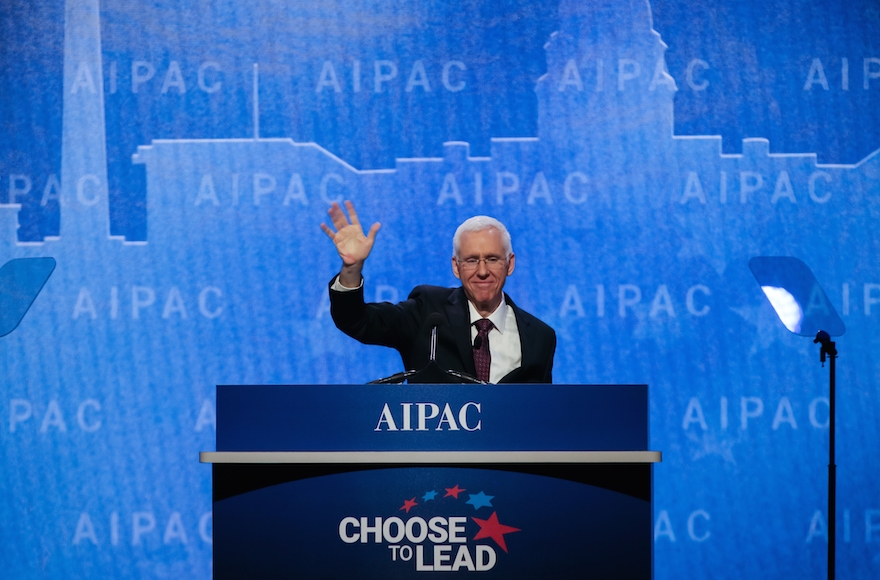

AIPAC President Mort Fridman addressing participants at the AIPAC Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., March 4, 2018. (AIPAC)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — On the second floor of the downtown convention center here, hundreds attending the annual policy conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee packed a standing-room-only hall. A bouncer stood outside to control the overflow crowd.

It wasn’t a session on boycotts, Iran or the peace process. It was mincha, the Jewish afternoon prayer service. Outside, smaller groups of Orthodox men gathered to form their own prayer quorums. High school students in kippahs and long skirts sat against the walls chatting.

Meir Raskas knows it hasn’t always been this way. When he began attending the policy conference 10 years ago, Orthodox prayer services would draw about 20 people.

“It’s definitely enlarged,” said Raskas, an investor and AIPAC volunteer from Baltimore. “All the people on the correct side of the argument are all here rallying around the cause.”

AIPAC does not divide its 18,000 attendees by religious denomination, but delegates to the conference say the Orthodox contingent is growing. While the Orthodox don’t make up a majority of conference participants this year, Orthodox Jewish leaders and laypeople say their rising numbers at the event are a sign that they are translating long-held sentiments into political power. AIPAC’s newly installed president, Morton Fridman, belongs to a Modern Orthodox synagogue in Teaneck, New Jersey.

“The Orthodox segment of the community is most connected to and passionate about Israel,” said Nathan Diament, executive director of the Orthodox Union Advocacy Center, citing survey data. “AIPAC is a central vehicle for Israel advocacy, so more and more Orthodox people want to be involved in that.”

Non-Orthodox attendees, meanwhile, did not seem worried that a growing Orthodox contingent would eclipse their concerns. But some did worry about a growing divide on Israel policy between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews.

The Orthodox presence at AIPAC is visible everywhere. Teenagers, students and adults in kippahs, if not black hats, freckle the hallways. Dozens of members of NCSY, the Modern Orthodox youth group, clustered in a semicircle in an alcove Sunday as their leader told them a story about a plummeting plane sparking the passengers’ faith in God.

For some Orthodox participants, the question isn’t why their numbers are growing but why it took so long. Many Orthodox Jews see Israel as a fulfillment of biblical prophecy, and Modern Orthodox Israelis largely identify with the nationalist wing of Israeli politics. References to Israel and Jerusalem infuse the prayers that Orthodox Jews say daily, and their children are more likely to spend extended periods of time there studying in yeshivas.

“My background, like so many of the people in that room, had Zionism as part of their education,” said Rabbi Dovid Asher of the Orthodox Knesseth Beth Israel in Richmond, Virginia, though he eschews denominational labels. “It’s only a fraction of American Jewry that is so-called Orthodox and it’s critical that we have wide representation. ”

But the growing numbers are also the result of a concerted effort by AIPAC to draw religious Jews of all denominations into its ranks. The lobby’s Synagogue Initiative, launched in 2005, recruits rabbis to bring congregants to the conference, along with giving them pro-Israel material to insert into weekly sermons. And all food served at AIPAC events has been kosher, as a policy, for more than a decade.

“AIPAC has become not only more and more welcoming but has actively recruited in the Orthodox community,” Diament said. “That and other things have prompted a two-sided equation in which the Orthodox community is becoming more and more engaged, and AIPAC has been very welcoming.”

Non-Orthodox rabbis were worried about widening political divides between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews. A poll last year, for example, found that most non-Orthodox Jews disapproved of President Donald Trump, while most Orthodox Jews approved of him. The Orthodox tend to be much more supportive of the settler movement than non-Orthodox Jews; Trump’s ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, is an Orthodox Jew who as a private citizen raised money for a West Bank settlement.

The denominations’ respective leaderships also disagree on how much American Jews should influence religious controversies in Israel, such as the debate over prayer arrangements at the Western Wall. The non-Orthodox movements have made pluralism in Israel a priority. Orthodox groups tend to support the status quo represented by Israel’s Orthodox Chief Rabbinate.

“Trump still enjoys wide support among Orthodox Jews in America, less so among non-Orthodox Jews,” said Rabbi Jonathan Blake of Westchester Reform Temple in New York. “The result has become so divisive, it’s actively dividing between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews. I am concerned that Reform Jews and Orthodox Jews are not on the same page. We have been brought into friction.”

But they also stressed that AIPAC has been able to avoid those divisions by sticking to advocating for security issues. AIPAC’s legislative agenda seldom strays far from the preferences of the sitting Israeli government; the current organizational consensus is well in line with the right-wing policies of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and most Orthodox pro-Israel activists.

“No other organization has tapped into the Orthodox community except those that are solely Orthodox,” said Rabbi David-Seth Kirshner of the Conservative Temple Emanu-El, in Closter, New Jersey. “We have liberals and conservatives, but we’re not divided in our desire for a safe and secure Israel.”

Non-Orthodox rabbis say they don’t feel threatened by a larger Orthodox presence. A few told JTA they appreciated that the AIPAC conference, which seldom touches on religion, is a place where leaders of all movements can gather.

Rabbi Denise Eger of the Reform Congregation Kol Ami in West Hollywood, California, said she was heartened by how well she got along with Orthodox and Conservative colleagues on a recent AIPAC trip to Israel. And her synagogue delegation is growing, too. Last year, one congregant joined her at the conference. This year she brought seven.

“At the heart of it, we can have different ideas about what Zionism is, and what Israel’s policies ought to be,” Eger said. “But this is one of the few places in Jewish life where we’re all in the same room.”