Why Jews care that Roy Moore’s ‘Jewish lawyer’ is actually Christian

Published January 5, 2018

Martin Wishnatsky, a lawyer first hired by the former Alabama Senate candidate in 2012, was the so-called Jewish lawyer referenced by Moore’s wife at a December campaign rally, according to Al.com. Wishnatsky, 73, was raised in a secular Jewish home in New Jersey, but later came to believe in Jesus and converted to Mormonism before becoming an evangelical Christian.

So does that make Wishnatsky Jewish or not? There is no definitive answer. It hinges on an age-old debate: Is Judaism primarily an ethnicity, a religion or a culture?

“You’re both,” said Wishnatsky to Al.com, regarding whether he was Christian or Jewish. “You’re a Jewish person that’s accepted Christ. Jesus was a Jew. Most Jews are not religious. That’s how I grew up.”

Wishnatsky isn’t the only Jew who has embraced Christianity and travels in Republican circles. Jason Chaffetz, the former Utah congressman, was raised Jewish and converted to Mormonism. And Jay Sekulow, a lawyer for President Donald Trump, came to Christianity as a Jew for Jesus.

For millennia, Jews have struggled with how to define people who have converted out of the religion, whether due to duress or by choice. A Talmudic sage, Rabbi Elisha ben Abuya, was denounced as the “Other” after he rejected Judaism. During the Spanish Inquisition, many Jews opted to convert to Christianity rather than facing expulsion or death. Rather than read them out of the community, religious authorities treated them as “anusim,” or Jews who converted under duress. Five centuries later, some of their descendants retain elements of Jewish practice and have sought to reconnect with Judaism.

Jews who have converted to other faiths are treated occasionally as apostates. The most famous recent example was Brother Daniel, a Polish Jew who became a Carmelite monk during the Holocaust. When Brother Daniel applied to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return, which grants automatic citizenship to those with at least one Jewish grandparent, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that he was ineligible because the law does not include Jews who practice another religion.

Many Jews today still opt for other religions. In addition to 5.3 million Jews in the United States, the Pew Research Center counted another 2 million people who either were raised Jewish or had a Jewish parent, and now, like Wishnatsky, identified with another religion — usually Christianity. These people retain their Jewish identity but, according to Pew, don’t affiliate with other Jews or do anything particularly Jewish.

Many in this group “say they think of themselves as Jewish precisely because of their Christianity (e.g., because Jesus was Jewish),” the Pew report says. “But compared with Jews by religion, those in the Jewish background and Jewish affinity categories are substantially less involved in Jewish organizations and the Jewish community, and are less likely to participate in uniquely Jewish rituals and practices.”

Historically, Jewish scholars and authorities tend to leave the door open for those who have opted out — saying that Jewish identity is an issue of ancestry, not faith. For the Orthodox and Conservative movements, the only qualification one needs is matrilineal descent — having a Jewish mother — or converting to Judaism. Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism say a child of any Jewish parent is a Jew.

So while rabbis generally encourage Jewish practice, even an Orthodox rabbi will say that a Jew who now attends church is just as Jewish as, well, the rabbi. That also may be why one-third of American Jews say someone can believe in Jesus and still be Jewish.

“Jewishness is about neither religion nor race,” writes Rabbi Zalman Nelson at Chabad.org, the website of the Hasidic outreach movement. “Unlike a race, you can get in, but unlike religion, once you’re in you can’t get out. … Once you are a part of this people, you are the entire people. As Israel is eternal, so your bond with them is irreversible, unbreakable and eternal.”

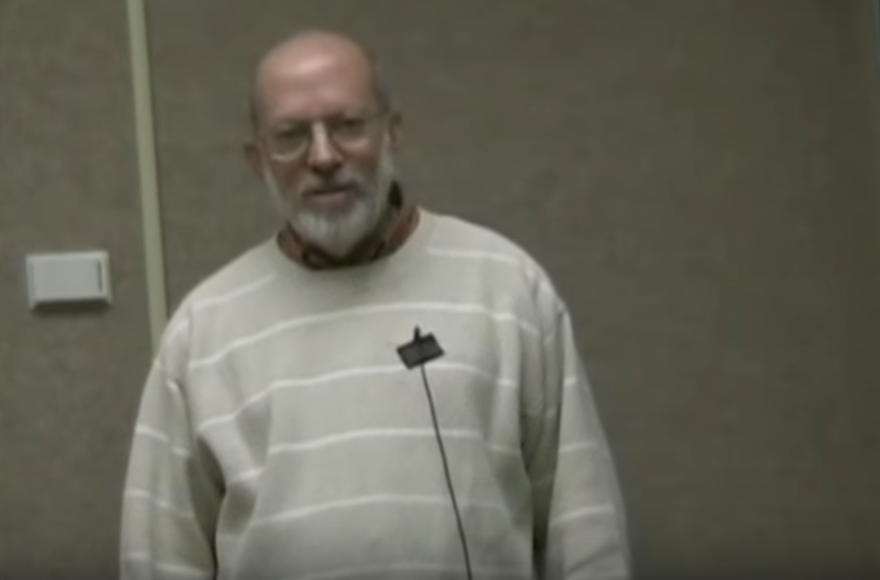

Martin Wishnatsky, seen in a 2009 photo, identifies as evangelical and calls himself a Messianic Jew. (Screenshot from YouTube)

But at the same time, synagogues and Jewish organizations are generally suspicious of Jews who practice and evangelize Christianity, especially when they identify as “Messianic Jews.” One of the few things the fractious American Jewish community basically agrees on is that Messianic Jews — those who perform Jewish rituals but accept Jesus as the Messiah — have no place in Jewish programs, events and surveys. In addition to embracing the very tenet that delineates Christians from Jews — belief in Jesus as Messiah — Messianic Jews are viewed not only as holding different beliefs but also as seeking to convert Jews to them.

“Jews for Jesus have always been seen as a missionary group,” said Rabbi Alan Brill, the chair for Christian-Jewish studies at Seton Hall University. “Historically, for the last millennium, to convert to Christianity has been seen as a negation of one’s Jewish identity.”

Jews tend to get more exercised over Messianic Jews than mere apostates because Messianic Jews inhabit a nervous-making middle ground, suggesting Judaism and Christianity are theologically compatible. That plays into age-old anti-Semitic notions — since rejected by the Catholic church and other sects — that Christianity is the mere “completion” or fulfillment of Judaism.

Wishnatsky, in addition to identifying as evangelical, called himself a Messianic Jew. But there’s a difference between Jewish converts to Christianity and Messianic Jews. The latter, while believing in Jesus, still say they are practicing Judaism and observe other Jewish rituals.

There are also relatively few Messianic Jews. The most prominent of these organizations, Jews for Jesus, receives funding from evangelical groups and says 30,000 to 125,000 Jews worldwide believe in Jesus.

But Jews for Jesus hasn’t given up on attracting more Jews to its fold. A recent study commissioned by the group found that one-fifth of Jewish millennials believe Jesus was God in human form.

“It was very hopeful from our perspective,” Susan Perlman, the San Francisco-based group’s director of communications, told JTA in October. “This was a generation that was spiritual, that is willing to engage in the subject of whether or not Jesus might be the Messiah. All we can ask for is an open mind to engage with the Bible, engage with the culture and look at the possibilities.”