When Jewish justices got the Supreme Court to shut down on Yom Kippur

Published September 29, 2017

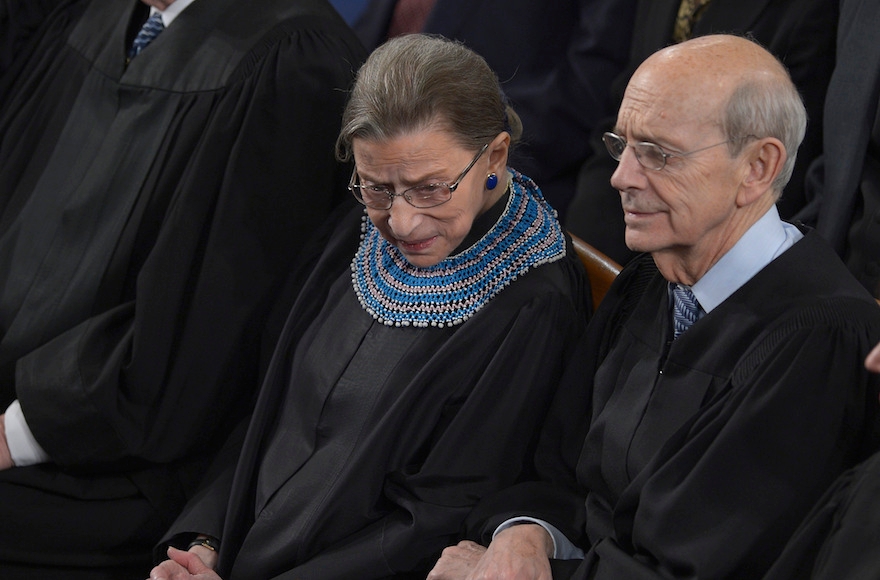

Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer listening to President Barack Obama deliver his State of the Union address before a joint session of Congress in the U.S. Capitol, Jan. 28, 2014. (Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON (JTA) – Since 1995, the U.S. Supreme Court has not held public sessions on Yom Kippur. Since the court opens its term on the first Monday in October, it is not unusual for the Jewish Day of Atonement to arrive just as the court begins its public work.

ADVERTISEMENT

How the Supreme Court came to observe the Jewish High Holiday is a story about religious diversity on the court, the quiet perseverance of two justices and an unexpected illness.

In an impromptu appearance at a synagogue here last week on Rosh Hashanah, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recounted how she and fellow Jewish Justice Stephen Breyer approached Chief Justice William Rehnquist and explained that Jewish lawyers who had been “practicing their arguments for weeks” should not be required to choose between religious observance and representing their clients before the court. According to Ginsburg, Rehnquist agreed.

But Ginsburg was being respectful of the memory of Rehnquist – cognoscenti have slightly less gracious memories of his role in the change.

There were no Jewish justices on the Supreme Court in the almost quarter century between the resignation of Abe Fortas on May 15, 1969, and Ginsburg’s swearing-in on Aug. 10, 1993. (Breyer joined the court on Aug. 3, 1994.) I appeared before the court as private counsel a number of times between 1971 and 1994, and the Supreme Court clerk was always accommodating to Jewish religious observance. Cases in which I was scheduled to argue orally were scheduled for dates that would not conflict with Jewish holidays.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1994, I was scheduled for two appearances during a Supreme Court session in March that included Passover. At my request, the arguments were scheduled so as not to conflict with the first and last two days of the holiday.

A lawyer asking for an argument to be rescheduled was one thing; a Supreme Court justice sitting out an argument was quite another.

Yom Kippur in 1993 and 1994 came in September, so there was no religious conflict during Ginsburg’s first two years and Breyer’s freshman year on the court. But in 1995, Yom Kippur was on Oct. 4 – a Wednesday on which the court was scheduled to hear oral argument. No counsels apparently had requested that their cases be rescheduled. Although the court’s Hearing Calendar had arguments scheduled for that date, they were abruptly postponed. The court took the day off on Yom Kippur, as it has done ever since.

Those of us who followed the court closely and were battling for recognition of Jewish religious rights were curious as to how this happened. The story – as I heard it at the time from a knowledgeable source – did not portray Rehnquist as cordially accommodating to Jewish religious observance.

The account I heard then was that Ginsburg and Breyer had approached Rehnquist after oral arguments were scheduled for that Oct. 4. The two Jewish members asked the chief justice to be respectful of their religious identity and postpone the arguments scheduled for Yom Kippur.

Rehnquist, however, had not accommodated Jewish observance in a 1986 case in which I had argued on behalf of an Orthodox Jewish Air Force psychologist who wanted to wear a yarmulke with his military uniform. Rehnquist had written the Supreme Court’s majority 5-to-4 opinion rejecting the First Amendment claim.

Before she was nominated to the Supreme Court, Ginsburg as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals — along with Antonin Scalia and Kenneth Starr, judges at the time — had voted in favor of the psychologist’s motion to rehear the lower court’s rejection of the yarmulke request. (Following the high court’s rejection, Congress would enact a law, still in effect, that grants military personnel in uniform a statutory right to wear a neat and conservative religious article of clothing.)

In 1995, according to the version of the story I heard, Rehnquist turned down the request of Ginsburg and Breyer to reschedule the court date to accommodate Yom Kippur. He told them that they could, if they chose, absent themselves on Yom Kippur and still vote, pursuant to the court’s practice, after listening to the audio tapes of the oral arguments.

Soon thereafter, however, Rehnquist found that he, too, would be unable to sit with the court on Oct. 4 because his painful back condition required medical treatment on that day.

According to my sources, this gave the two Jewish justices an unexpected opportunity. They approached John Paul Stevens, the most senior justice who would be presiding if Rehnquist were absent. They pointed out to Stevens that if the two of them were not on the bench on Oct. 4, only six justices would sit to hear oral arguments on that day. Although that number is technically a Supreme Court quorum and the absent justices could vote after listening to audio tapes, Stevens agreed that the optics of such a diminished panel would be less than ideal. Stevens then postponed the Yom Kippur session, and the practice stuck.

This year’s Yom Kippur falls on Friday night and Saturday morning, Sept. 29-30, and the court won’t convene until Monday, Oct. 2.

But thanks to Justices Ginsburg, Breyer and Stevens, the next time a public session falls on Yom Kippur, a sign of respect for Jewish observance will again prevail.

(Nathan Lewin is a Washington lawyer who has argued 28 cases before the Supreme Court and is on the adjunct faculty of Columbia Law School.)