When does life begin? There’s more than one religious view

Published September 8, 2021

The most restrictive abortion law in the country went into effect on Sept. 1, 2021, after the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-4 to deny an emergency appeal. In Texas, abortions are now illegal as early as six weeks into a pregnancy — before many women and girls know they are pregnant.

To date, 13 other states have passed laws establishing this six-week limit, but they face court challenges for state interference in women’s constitutionally protected right to terminate a pregnancy.

Texas got around that problem by forbidding state officials from enforcing it. Instead, the state authorized private citizens to sue anyone who helps these women — family members, rape crisis counselors, medical professionals — and promises at least US$10,000 plus attorneys’ fees if they win. Opponents have dubbed it the “sue thy neighbor” law.

These so-called heartbeat bills outlaw abortion after an embryo’s cardiac activity can be detected – generally around six weeks – although many doctors argue that the idea of a heartbeat at this stage is misleading since the embryo does not yet have a developed heart.

In addition, these laws generally refer to the fetus as an “unborn human individual.” These are strategic choices designed to muster support for the idea of fetal personhood, but they also reveal assumptions about human life beginning at conception that are based on particular Christian teachings.

Not all Christians agree, and diverse religious traditions have a great deal to say about this question that gets lost in the polarized “pro-life” or “pro-choice” debate. As an advocate of reproductive justice, I have taken a side. Yet as a scholar of Jewish Studies, I appreciate how rabbinic sources grapple with the complexity of the issue and offer multiple perspectives.

What Jewish texts say

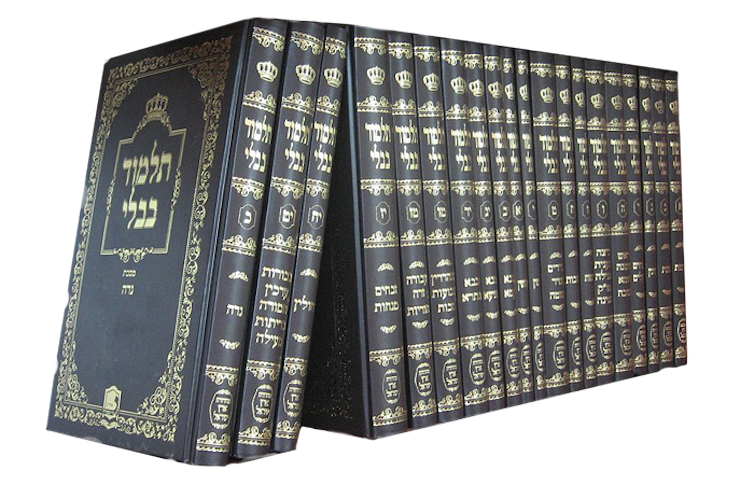

Traditional Jewish practice is based on careful reading of biblical and rabbinic teachings. The process yields “halakha,” generally translated as “Jewish law” but deriving from the Hebrew root for walking a path.

Even though many Jews do not feel bound by halakha, the value it attaches to ongoing study and reasoned argument fundamentally shapes Jewish thought.

The majority of foundational Jewish texts assert that a fetus does not attain the status of personhood until birth.

Although the Hebrew Bible does not mention abortion, it does talk about miscarriage in Exodus 21:22-25. It imagines the case of men fighting, injuring a pregnant woman in the process. If she miscarries but suffers no additional injury, the penalty is a fine.

Since the death of a person would be murder or manslaughter, and carry a different penalty, most rabbinic sources deduce from these verses that a fetus has a different status.

An early, authoritative rabbinic work, the Mishnah, discusses the question of a woman in distress during labor. If her life is at risk, the fetus must be destroyed to save her. Once its head starts to emerge from the birth canal, however, it becomes a human life, or “nefesh.” At that point, according to Jewish law, one must try to save both mother and child. It prohibits setting aside one life for the sake of another.

Although this passage reinforces the idea that a fetus is not yet a human life, some Orthodox authorities allow abortion only when the mother’s life is at risk.

Other Jewish scholars point to a different Mishnah passage that imagines a case of a pregnant woman sentenced to death. The execution would not be delayed unless she has already gone into labor.

In the Talmud, an extensive collection of teachings building on the Mishnah, the rabbis suggest that the ruling is obvious because the fetus is part of her body. It also records an opinion that the fetus should be aborted before the sentence is carried out so that the woman does not suffer further shame – establishing the needs of the woman as a factor in considering abortion.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]

Making space for divergent opinions

These teachings represent only a small fraction of Jewish interpretations. To discover “what Judaism says” about abortion, the standard approach is to study a variety of contrasting texts that explore diverse perspectives.

Over the centuries, rabbis have addressed cases related to potentially deformed fetuses, pregnancy as the result of rape or adultery, and other heart-wrenching decisions that women and families have faced.

In contemporary Jewish debate there are stringent opinions adopting the attitude that abortion is homicide – thus permissible only to save the mother’s life. And there are lenient interpretations broadly expanding justifications based on a women’s well-being.

Yet the former usually cite contrary opinions, or even refer a questioner to inquire elsewhere. The latter still emphasize Judaism’s profound reverence for life.

According to a 2017 Pew survey, 83% of American Jews believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. All the non-Orthodox movements have statements supporting reproductive rights, and even ultra-Orthodox leaders have resisted anti-abortion measures that do not allow religious exceptions.

This broad support, I argue, reveals the Jewish commitment to the separation of religion and state in the U.S., and a reluctance to legislate moral questions for everyone when there is much room for debate.

There is more than one religious view on abortion.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 19, 2019.