Was Hitler’s anti-Semitism different than Khamenei’s?

Published September 17, 2015

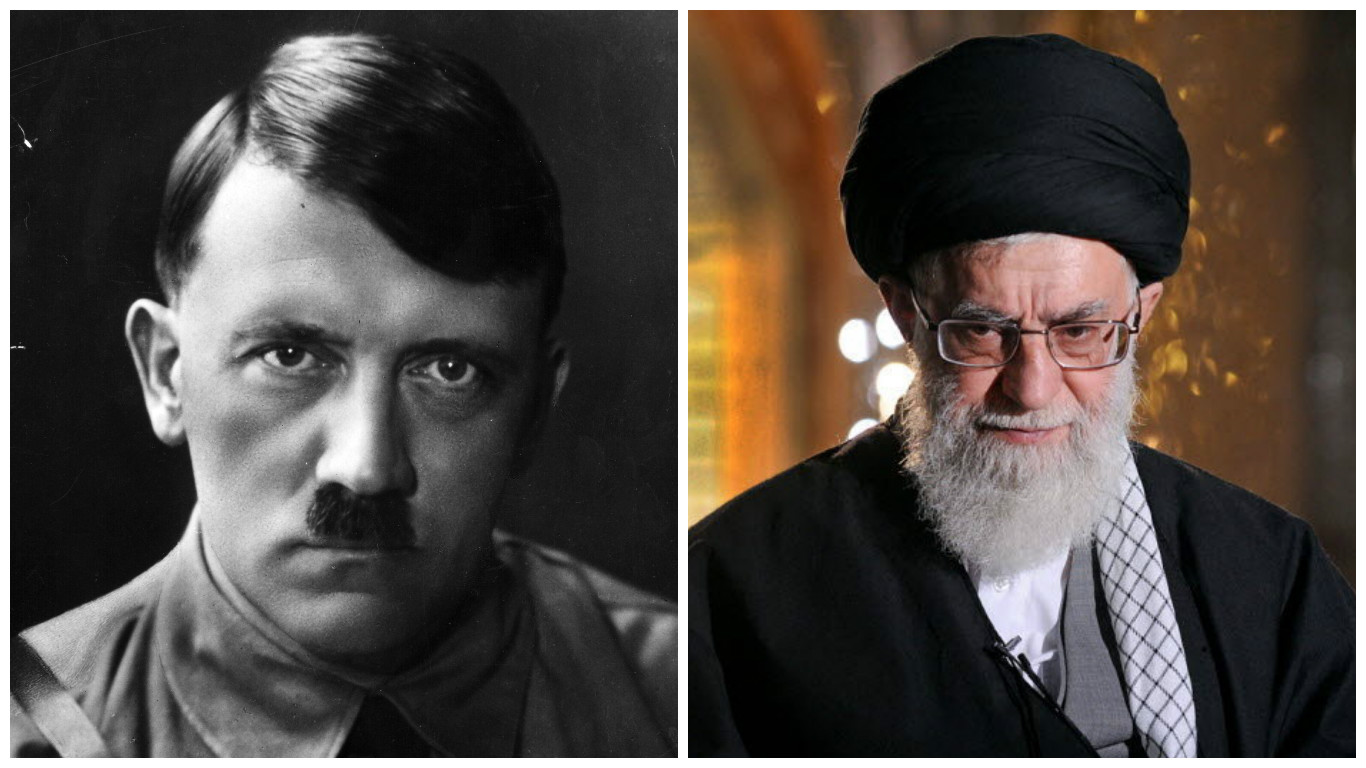

Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler (Heinrich Hoffmann/Getty Images) and Iranian supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (AP Images).

Adolf Hitler’s anti-Semitism is generally seen as an aspect of his brutally absolutist German nationalism. For the Nazi dictator, the Germanic Aryans reigned supreme, the theory goes, and Jews, Slavs and Gypsies needed to be eradicated to purify this master race.

However, Yale University Holocaust Historian Timothy Snyder has argued that Hitler’s anti-Semitism was actually rooted in an even more extreme — and far more sinister — way of seeing the world.

“What Hitler does is he reverts,” Snyder explained in an interview with The Atlantic last week. “He reverses the whole way we think about ethics, and for that matter the whole way we think about science.”

In Hitler’s worldview, which Synder termed “racial anarchy,” human life has no inherent meaning outside of savage competition between the races, he said. The Nazi dictator thought “races struggle against each other, kill each other, starve each other to death, and try and take land” — this is life in its purest and most true form.

In Hitler’s eyes, Snyder said, the Jews subvert this natural order by introducing the idea that people can see each other as human beings. It was to return to a state of nature — not for nationalistic reasons — that Hitler wanted the Jews wiped out.

Synder lays out these ideas in “Black Earth: “The Holocaust as History and Warning,” published last week.

Talking to The Atlantic, he underlined one of the book’s major points: Hitler’s anti-Semitism went far beyond mere hatred of Jews.

Snyder said that Hitler wasn’t any more or less anti-Semitic than Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, who he noted recently predicted Israel’s demise within 25 years. The difference between the two leaders, he said, is that Hitler’s anti-Semitism was his raison d’être.

In fact, Synder argued it would wrong to even describe Hitler politics as nationalistic, because the dictator didn’t truly believe in the idea of statehood.

“Hitler explicitly said that states are temporary, state borders will be washed away in the struggle for nature,” Snyder said. His decisions as fuhrer weren’t truly concerned with strengthening the German state, but rather were designed to make Germany an “instrument to destroy other states,” in accordance with life’s true, primal meaning.

“As far as he was concerned, if the Germans lost, that was also alright. And that’s just not a view that a nationalist can hold,” Synder said. “If we think that Hitler was just a nationalist, but more so, or just an authoritarian, but more so, we’re missing the capacity for evil completely.”

Snyder cited Barack Obama’s interview with The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg in August, in which the president argued that the Khamenei’s hate filled anti-Semitic ideology does not preclude him making rational decisions based on the principle of self-preservation.

By comparison, Snyder said, the supposed evil of the Jews was so central to Hitler’s worldview that the Final Solution was entirely rational for him.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.