This Jewish lawmaker wanted to keep Chinese immigrants out. Should a park be named after him?

Published May 8, 2018

A view of the Julius Kahn playground in San Francisco. (Omunene/Flickr Commons)

SAN FRANCISCO (J. the Jewish News of Northern California via JTA) — Julius Kahn III grew up in San Francisco, playing in Julius Kahn Playground, named for his grandfather. The view from this clearing in the opulent Presidio Heights neighborhood is among the best in the city, meaning it’s among the best in any city. That won’t change anytime soon, but the name of the park soon may.

ADVERTISEMENT

Several Chinese American groups, working with the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, and two Chinese American members of the S.F. Board of Supervisors have moved to strip Kahn’s name from this playground and its adjoining ballfield and sports courts — all with the blessing of the S.F.-based Jewish Community Relations Council.

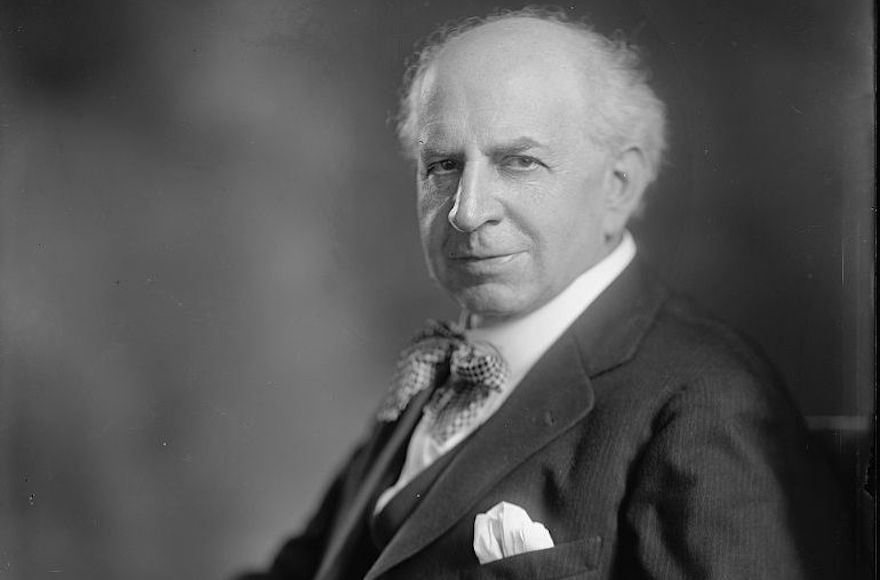

The rationale: The elder Kahn, a Republican from San Francisco who served 12 terms in Congress between 1899 and his death in 1924, championed an extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1902 prohibiting immigration by Chinese laborers.

While doing so, he approvingly read to Congress excerpts from a travel writer’s 1853 journey to the Far East, describing the Chinese as “morally, the most debased people on the face of the [E]arth.” Kahn personally endorsed these views, stating they are “undoubtedly equally applicable to any Chinese community in our country.”

A tremendously influential legislator, Kahn was successful in getting the votes for the act’s extension, which made Chinese immigration permanently illegal and legally enshrined anti-Chinese sentiment until its repeal in 1943.

On April 24, Supervisor Norman Yee introduced a resolution calling for the city’s Recreation and Park Commission to change the facility’s name.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We don’t want to send him, as a person, to the dustbin of history,” explained Hoyt Zia, the president of the board of the S.F.-based Chinese Historical Society of America. “But we’ve got a park in a city with one of the largest Asian populations in the country. Do we want to have things named after people who hated Asians? We use the park every day.”

At least one local Jewish organization understands Zia’s perspective.

“We were contacted a few weeks ago by Recreation and Park Commission Vice President Allan Low on behalf of the Chinese Historical Society’s coalition and asked to support this resolution to rename the park,” Jessica Trubowitch, the JCRC’s director of public policy and community building, said in a May 2 statement.

“When we were contacted, we had no hesitation in supporting the resolution,” the statement continued. “It’s time to right a wrong, and to ensure that our civic institutions and public spaces celebrate our contemporary values. We share an understanding that immigrants have and will continue to be an integral part of this city.”

On April 30, Trubowitch attended, on behalf of JCRC, a press conference at which Zia called Kahn “anti-immigrant” and said he would “fit right in with this [presidential] administration,” according to the San Francisco Examiner. “The names of places should reflect the city as it is now,” he added, according to the paper.

Reached at his San Ramon home, 86-year-old Julius Kahn III was unaware of the developments surrounding the playground, but not surprised.

“I figured they were going to do something like that,” he said. “If they want to raise that issue, there’s not a hell of a lot I can do about it. It’s the height of stupidity. I think it’s a damn crime to hang something on him for one instance in a career that I know he regretted doing but went along with the party at that time.”

Whether Kahn felt remorse for championing the Chinese Exclusion Act, a federal law signed in 1882 by President Chester A. Arthur, is difficult to know. That’s the family’s claim, and Kahn III says it’s true, but he never knew his grandfather, having been born seven years after his death.

What is certainly true is that the anti-Chinese immigration stand was the party line of the day. And, say Bay Area Jewish historians, virulently anti-Chinese sentiment was also par for the course among Kahn’s fellow German Jewish gentry of San Francisco.

Julius Kahn’s efforts helped extend the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act. (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

“They were a civilizing influence on a kind of boomtown of young men running wild,” said Fred Rosenbaum, the founder of Berkeley-based Lehrhaus Judaica and the author of many books about San Francisco Jewry. “But they did have a giant blind spot. And that had to do with anti-Asian racism. They really were leading participants in the persecution of the Chinese in California.”

Added historian and author Ava Kahn (no relation to Julius): “Julius Kahn was one of the few Congresspeople who was against a literacy test for immigrants. So he was not anti-immigrant. He was anti-Asian immigrant.”

So was Jacob Voorsanger, the famed rabbi of the city’s Congregation Emanu-El (and founder of the local Jewish newspaper that became J.), who described the Chinese as a “non-assimilative race” who were “unable to mix with caucasians” in the pages of J.’s predecessor, the Emanu-El.

Levi Strauss summarily dismissed 180 Chinese workers from his famous blue jeans factory after thugs targeted the Chinese in 1877 riots. Adolph Sutro, a social liberal, one of the city’s greatest industrialists and philanthropists, and, in 1894, the first Jew to be elected mayor of a major U.S. city, boasted about having never hired “a chinaman.” He wrote that “the very worst emigrants from Europe are a hundred times more desirable than these Asiatics.”

Rosenbaum’s research has revealed that Jewish communities on the East Coast and in the Midwest, where there were few Chinese, were confused and horrified at San Francisco Jews’ peculiar animus — which, to be fair, they shared with much of the city’s white establishment. Many worried that the fanatical drive to limit Asian immigration would eventually boomerang on Jews — and, with the Immigration Act of 1924, it did: Jews from much of Europe were barred from entry, intensifying the magnitude of the Holocaust.

When asked if the names Sutro, Strauss and others should be stripped off San Francisco’s map, Allan Low said that’s a discussion for later.

“Racism and dark history surrounds us,” said Low, pro bono attorney for the groups looking to change the name of the playground and one of seven commissioners appointed by the mayor to govern the S.F. Recreation and Parks Department. “But in my view, we can only take name changes one at a time.”

In fact, the name of Julius Kahn Playground — which presents breathtaking views of the Golden Gate Bridge, Presidio and Marin Headlands — has already been changed. The actual playground portion of the facility was renamed for the late Jewish philanthropist Helen Diller after her foundation paid for its extensive and innovative renovation in 2003. The basketball and tennis courts, the green space and the baseball/softball diamond, however, are still named for Julius Kahn.

Whose name will be used next is not known. But both Julius Kahn III and his son, Steve, are pushing for Julius’ wife, Florence Prag Kahn, who took his seat in Congress after he died and served six terms, from 1925 to 1937.

Her grandson rattles off the accomplishments of the woman he used to ride streetcars with on the way to the movies: “She got the enabling legislation for the Golden Gate Bridge; she was the first woman on the Military Affairs Committee; she got the legislation and funding for Moffett [Federal Airfield] and the Alameda Naval Station; she got the funding for Alcatraz as a federal prison,” he said. “In a sense, my grandmother did more for the city than my grandfather.”

In fact, when the current-day Kahns talk about their family history, they spend a lot more time on Florence than they do on Julius, said Steve, 60.

He, too, played in Julius Kahn Playground as a kid growing up in San Francisco. “It was serene,” he recalled.

Unlike his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, Steve Kahn is not a lawyer. He’s a mechanic in El Cerrito.

He specializes in Asian imports.