This couple’s goal is to photograph every living Holocaust survivor

Published March 20, 2019

This article originally appeared on Kveller.

At first, it seems like John and Amy Israel Pregulman nailed the ideal “digital nomad” lifestyle. The very-much-in-love couple travels the country and the world side by side working for an organization they built together from the ground up.

“Every day we wake up and go, ‘We can’t believe we’re getting to do this,’” Amy tells me from the passenger seat of the car as the couple is en route to Boulder, Colorado, from their home in Denver.

But here’s the thing: The Pregulmans don’t have a tech startup, nor are their adventures spent scouring markets for handmade textiles or artisanal cheese. They’re not social media influencers. Instead, their project takes them to the homes of people who are often overlooked: Holocaust survivors.

KAVOD, the organization founded by the couple, has an impressive twofold mission. The first is to photograph every living Holocaust survivor before they die. The second: to help those survivors living in poverty with emergency assistance that helps them get food on the table and the medicine they need, among other things.

“It’s very privileged work,” says Amy, 49, the organization’s sole paid employee. “It’s a privilege to meet them, it’s a privilege to hear their stories and be a witness, and it’s a privilege to be able to make a small impact in their lives. And work together to be able to do that — it’s so unique.”

John, 61, has photographed nearly 800 survivors, and KAVOD has helped more than 1,000 survivors with donations. As of February, the couple’s work has taken them to 37 cities, including Prague, Krakow and Tokyo.

KAVOD is a Hebrew word that means “respect,” and that value is deeply ingrained in everything the organization does, from how John takes the pictures to how they distribute their donations.

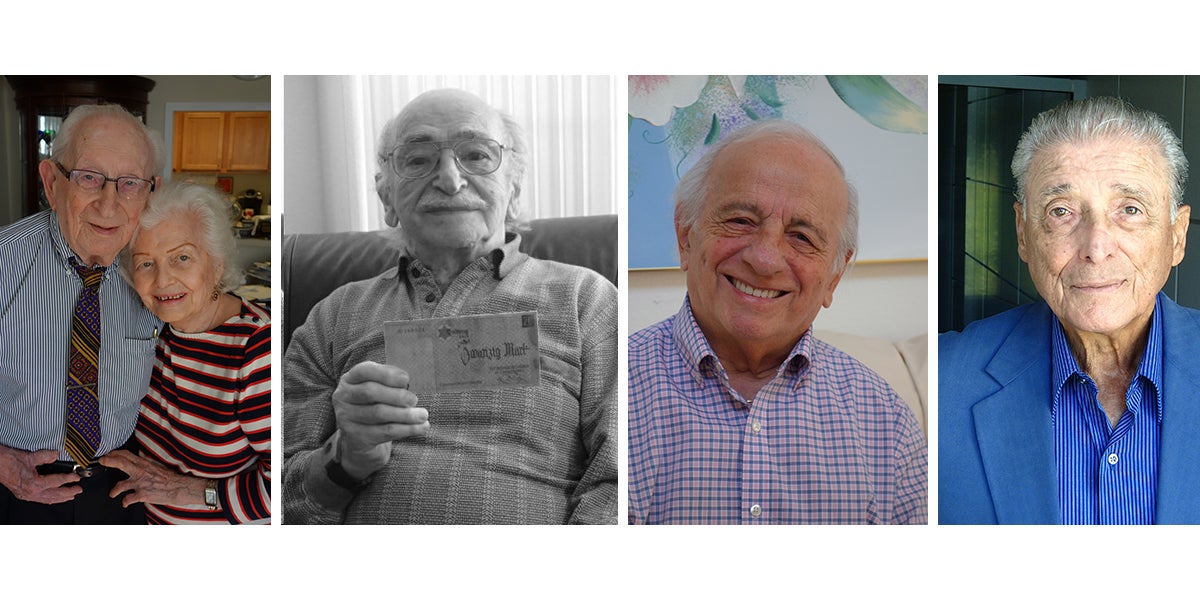

“You meet this incredible, positive, happy, accomplished people who overcame horrible experiences in most of their childhood or their teenage years, and in the beginning I would take the photos in black and white,” John says. “And they would say to me, ‘That really is kind of stark, and it makes us look sad, it doesn’t portray us the way we want to look.’”

So John started taking the photos in color. Since he thought a large, professional camera would intimidate his subjects, he decided to use a simple Sony digital. He also opts to have his subjects comfortably sitting, illuminated by natural light.

KAVOD started five years ago when John, a who is originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, was asked by a friend to photograph survivors at the Holocaust museum in Skokie, Illinois. For the former professional photographer, the connection with his subjects was immediate: He photographed 65 survivors in the span of three days. He decided to make this a passion project, going around the country and taking photos of survivors.

But the story of KAVOD is also, quite wonderfully, a love story. It was through this project that John and Amy met and fell in love.

One day, John was contacted by friends who lived in Memphis. Their father was a Holocaust survivor, and though he had never spoken about his experience to anyone, including his family, he wanted John to take his portrait.

“All of the sudden, he opened up to his children about everything,” John says.

John’s friends were also friends with Amy and arranged for the pair to meet. And so, as John’s friends got the gift of learning their father’s story for the first time, he got the gift of meeting his bashert.

“We started KAVOD in November of 2015, we got married in September 2016,” John says. “So this has really been a wonderful thing to grow this organization, as we grow together as a couple.”

The couple have six children from previous relationships between them, who they say are very supportive of their parents’ work.

The charitable aspect of the organization was a natural outgrowth of the photo project.

“In the beginning, we would mostly go into people’s home to take their pictures,” John says. “Inevitably, after you take an elderly lady’s picture she wants to give you something to eat, like your grandmother would.”

One time, while visiting a survivor in Orlando, “When she took me to her refrigerator, there was nothing there really,” he says. “She said, ‘I had to fix my air conditioner, so I used my grocery money for that and I’m just doing without.’”

For John and Amy, the idea was unacceptable. They soon found out that one-third of Holocaust survivors are living in poverty, according to Blue Card. In fact, 61 percent of the 100,000 survivors in the United States live on less than $23,000 annually.

Many survivors get a monthly payment, from the Claims Conference or Social Security, but when they have an emergency expense, it blows their budget and they have nothing to fall back on. So they end up using the money they would normally use for medicine or food.

“And so we decided that for KAVOD, we wanted to give emergency, confidential aid to survivors who have a quick need,” John says.

They decided to disperse the money through gift cards to Target and other stores “because anyone could go into a grocery store with a gift card and no one would make them feel like they were different,” according to Amy.

There are only three things that John and Amy need to know before they send aid: what the situation is, whether the person is a survivor and how much money they need. The organization’s board usually sends the money within three days.

“We understood that the process for getting funding and aid across the board was so complicated for them,” Amy says,” so we really wanted it to be simple.”

Though they may have streamlined the aid process, that doesn’t necessarily make it easier to bear witness to their subjects’ harrowing testimonials.

“There are days where it’s uplifting, you understand how important it is to bear,” Amy says, “and there are days when I go back to our hotel and I can’t move.”

“We read a lot,” John adds. “I’ve decided that the only books I’m reading these days are books about survivors we’ve met.”

Amy points out that John’s relationships with his subjects extend far beyond the photo shoot.

“He stays in touch with a lot of the survivors,” she says. “He’s just that guy who is a connector, and it comes out in every way, including the photos.”

With the recent rise of nationalism and anti-Semitism around the world, John and Amy feel like their work is more important than ever. The couple — who visit a different place almost every week for their work — have no thoughts of slowing down. They’re planning a visit to Israel this summer to take pictures of survivors there.

“We will continue to do this as long as there are survivors,” says John. “We’ve got 10 or 15 more years, and we’re not thinking of it beyond that.”