These 10 Yiddish words will get you through quarantine

Published May 20, 2020

This story originally appeared on Kveller.

We’ve been self-quarantining for more than 40 days and 40 nights and, quite frankly, we’re running out of steam. Still, we can’t escape all the social media posts and articles (and our mother’s voices in our heads) telling us to make good use of this time.

Friends, editors, and even country singer Roseanne Cash reminded us that Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” when he was quarantined during the Great Plague. Actress — no, sorry, lifestyle expert Gwyneth Paltrow urged us to write a book, teach ourselves to code online and learn a language. Teen idol Harry Styles upped the ante when he told us he’s learning sign language and Italian.

But in between cooking every single meal — to say nothing of snacks — and motivating our kids to stay focused on their distance learning assignments, just how are we supposed to find the time to learn a new language? (Moreover, how can we even practice said language when our mouths are pretty much always filled with cookies?)

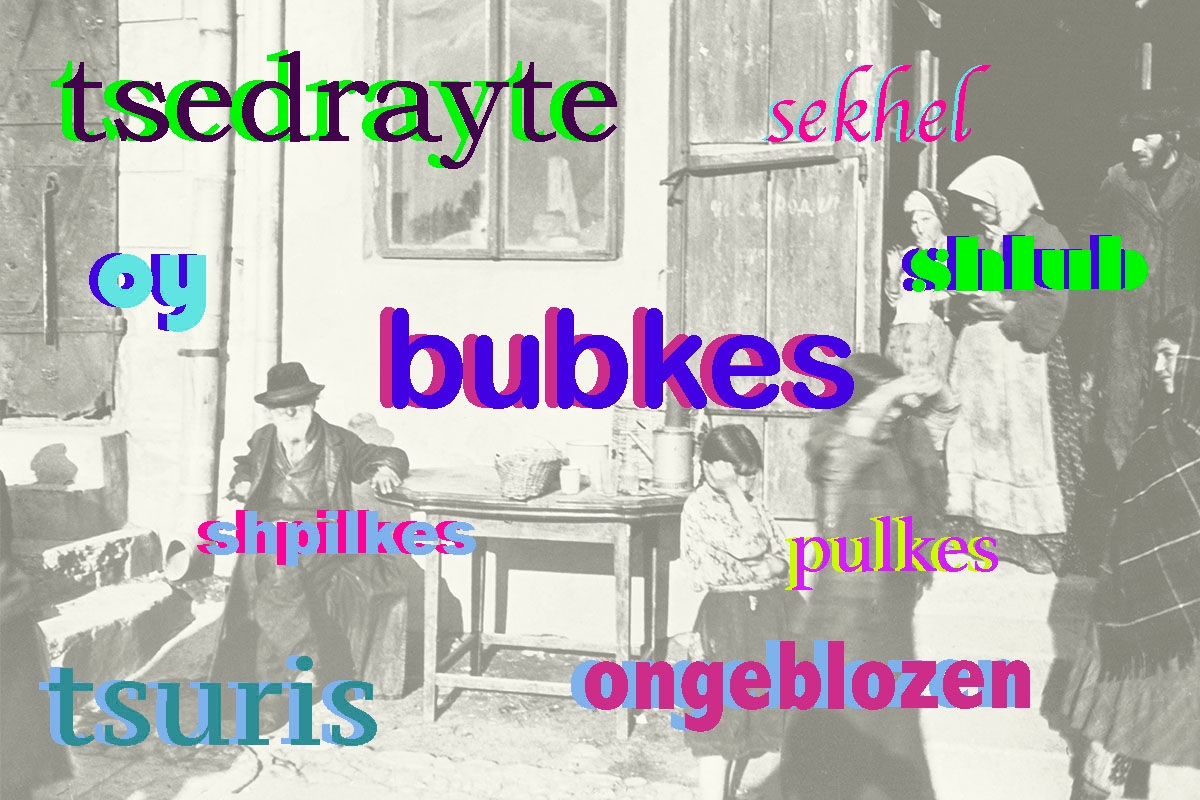

Here’s one thing we can find the time to do, however: We could all learn just a few words of a new language. Why not spend part of your “free time” at home brushing up on some of your bubbe and zayde’s favorite Yiddish words?

In the shtetl, Yiddish was the language that allowed Eastern European Jews to talk freely among themselves without fear of reprisals. In American Jewish homes, it was the language that grandparents spoke when they didn’t want the kinder to know what they were talking about. And now, if your kids are literally all over you 24/7, wouldn’t it be nice to have a secret language when you want to have a discreet chat with your partner?

So now that you’ve binge-watched “Unorthodox,” it’s time to get off your tuchas and start using your keppe (head)! These 10 Yiddish words — each one loaded with emotion and angst, and boy do we have plenty of that! — will come in handy to describe this pandemic mishegas (craziness).

1. Tsedrayte

adj. (tsuh-DRATE) All mixed up, confused.

Before the COVID-19 virus, tsedrayte meant we couldn’t remember if we promised to meet a friend for lunch on Thursday or Friday. Now we don’t know what day of the week it is. These days, just getting the mail makes us tsedrayte. Do we leave the letters on the floor for 24 hours? Do we wipe the package before we put it on the floor or wash our hands and then wipe the package? And what do we do after we open it?

2. Shpilkes

(SHPILL-kiss) Impatience, restlessness.

Before COVID-19, when our young kids had “ants in their pants,” we’d tell them to go outside and play. Now, however, we have to mask them up first, and watch them carefully so they stay six feet away from all the other kids who are also trying to get their shpilkes out. We used to go out to a yoga class; now when our little ones have shpilkes, we watch Cosmic Kids Yoga and do downward facing dogs right along with them.

3. Shlub

n. (SHLUB) A slob; some who dresses sloppily.

All this self-quarantining has made shlubs even shlubbier. Sweatpants and torn T-shirts have gone from weekend wear to all day, everyday wear — unless you’re one of those people who dons business casual from the waist up for your Zoom conference calls. If we’ve learned any fashion sense while being self-quarantined, it’s that a bra is optional.

4. Pulkes

pl. n. (PULL-keys) Thighs.

The word usually refers to cute, chubby baby thighs, but it can also mean those belonging to poultry. And with all the freezer diving we’re doing, we’ve discovered and eaten our fair share of pulkes in the last month. We’re counting the days till we can swap out our sweatpants for shorts and attend a summer barbecue, but we’re not certain our pulkes will be ready for public viewing after all we’ve eaten.

5. Sekhel

n. (SEH-khul) Common sense; good judgment.

Advice used to flow downstream. Our parents would nag us: “Have a little sekhel; do you really have to fly when you’re pregnant?” Now the tables have turned and we nag our parents: “Wash your hands. Wear a mask. You’re going to the supermarket? You’re old. Stay home!” And our kids? They have the computer sekhel we need: They’ve taught us how to complete the online school attendance form and how to limit our Facebook posts to “friends only” so we don’t embarrass them in front of “the whole world!” They’ve also taught us that there’s nothing wrong with eating ice cream twice a day.

6. Eyngeshparter

n. (AYN-guh-shpar-ter) A stubborn person; someone who cannot be convinced with logic.

These are the people who are protesting to end the shutdown before it’s safe, ordering “cures” on the Internet, and claiming the pandemic is all a hoax.

7. Bubkes

n. (BUP-kiss) Literally beans, nothing.

Something that’s worthless or that falls short of expectations. In this new normal, we’re getting used to bubkes in the toilet paper aisle, bubkes in our fresh vegetable drawer, and bubkes in our checking account.

8. Ongeblozen

adj. (un-geh-BLUH-zin) Sulky, pouty; a sourpuss.

Our kids used to get ongeblozzen when we said we couldn’t go out for pizza. Now everyone’s ongeblozzen because we spent all afternoon making dough from scratch… and we didn’t have the right kind of cheese. “It tastes funny. It doesn’t taste like Panzone’s pizza. Why can’t we go to Panzone’s?”

9. Tsuris

n. (TSORE-iss) troubles and worries; problems.

We can’t help worrying when our sister tells us she had a suspicious mammogram or our son hints that someone bullied him in school. But these days, instead of worrying about illness or money or school or our family or the future — we’re worried about all of it. Tsuris has gone from personal to universal.

10. Oy

int. (OY)

Perhaps the most popular Yiddish expression, oy conveys dozens of emotions, from surprise, joy, and relief to pain, fear and grief. Bubbe Mitzi used to say that just groaning “a good oy” could make you feel better.

So give a good oy, tie the shmata on your face — be sure to cover your mouth and your nose! — and try not to get tsedraye. Here’s hoping all this tsuris will be over soon.