‘The world’s largest legal’ Jewish party: How Taiwan’s small Jewish community expanded during COVID

Published March 24, 2021

(JTA) — British Jewish artist Leon Fenster loved his adopted city so much that he designed a Passover Haggadah with it as the theme. So when he left the Chinese capital for Taiwan in early 2020 at the outset of the pandemic, he made a vow: Next year in Beijing, again.

A year later, Fenster is still in Taiwan and has no plans to leave. Unlike virtually all Jews the world over, he spent the year getting involved in a robust, in-person Jewish community.

He now leads Shabbat services most weeks for the Taiwan Jewish Community group, a government-recognized organization for local Jews, playing bongos and singing. This week, he plans to join the community’s Passover seder. So many people have registered to attend that organizers say their rented commercial space, formerly home to a travel agency, may not be able to hold them all.

ADVERTISEMENT

The seder will be a lot like the community’s Purim party: packed, unmasked and with shared food. That’s because of Taiwan’s remarkable success at containing COVID-19. Daily life — religious life included — has continued virtually unimpeded in the island nation about 100 miles from mainland China since very early in the pandemic. The country of 23.5 million has had around 1,000 total COVID cases and just 10 deaths, and there are no restrictions on gatherings.

A Hanukkah party drew around 200 people, far more than the 60, at most, who attend Shabbat services on Friday nights. So did the Purim celebration last month.

“We said, ‘Well, this is probably the world’s largest legal Purim party,’” said Ben Schwall, president of the Taiwan Jewish Community.

ADVERTISEMENT

Schwall described his assessment as a joke, but he was likely correct. Israel’s successful vaccination drive did not come in time to permit large Purim events. Many of the countries with the largest Jewish populations, such as the U.S. and England, remain months away from allowing large gatherings. Others, such as France, are reimposing strict lockdown measures in the wake of new outbreaks.

Ben Schwall with his wife Emmy at the recent Purim party. He is dressed as a Chinese police officer. (Archi Chang)

The fact that life has gone on with little interruption in Taiwan has proven to be a boost for the Taiwan Jewish Community, the country’s main Jewish group outside of a local outpost of the Hasidic Chabad Lubavitch movement.

The pluralistic organization includes about 200 families, a mix of university students abroad, businesspeople, diplomats and other international expats. On top of that, friends and family and local non-Jews come to the group’s buzzed-about events, mostly meals and prayer services, to learn about Jewish culture and food. Schwall estimates that 10% of party attendees are devout Christians, many from the country’s large evangelical and pro-Israel population.

Taiwan’s sterling performance during the pandemic has kept some students and families who would have normally returned to universities and homes elsewhere, including Fenster. Others, attracted by the country’s sense of normalcy, moved to Taiwan for the first time over the last year.

“I talked to friends back in the States, and they said, ‘What the hell are you doing in Taiwan?’ I said ‘Well, they’re trying this novel approach here to education called school,” said Neil Peretz, a California lawyer and entrepreneur who moved his family to Taiwan in 2020. “And they have all the kids go to this building together the same age and they have these older people that are called teachers.”

Family activities are a big part of the Community group’s programming. (Archi Chang)

More than 25 years ago, Peretz spent a stint in the U.S. foreign service in China, where he learned Cantonese. He started looking for places to relocate after seeing his two school-age daughters struggle with online schooling, hoping that they could use the opportunity to also learn another language.

After studying the logistics of the immigration process, he applied under a “gold card” program Taiwan launched in 2018 to attract foreign professionals — an arduous feat that took months and several rounds of applications. More than 1,600 people have moved to Taiwan under the program since the pandemic began, compared to less than 400 the previous year, according to a recent New York Times report.

When his family arrived, they experienced a bit of culture shock, exacerbated by the fact that Peretz kept working on U.S. hours, with half a day’s time difference. (Taiwan is always 12 or 13 hours ahead of American East Coast time, and 15 or 16 ahead of California time.)

Joining the Jewish Community countered the family’s sense of dislocation. It also brought them into contact with a diverse set of Jews who are rooted in Taiwan or just visiting.

“I get to be a bit of a Jewish anthropologist,” added Peretz, who previously attended a Reform synagogue in Silicon Valley.

More kids at the recent Purim party. (Archi Chang)

International travelers are currently permitted to enter Taiwan for work or family reasons as long as they present a negative COVID test and quarantine on arrival. On a recent Friday night, Peretz said, he found himself sitting with French guests; before that, he had met Australians and Americans.

“Some of them will have different approaches to various melodies, prayers, etc,” Peretz said. “But it actually provides a great learning opportunity, because I think if you’re in a large congregation, in the States, let’s say, where there’s a lot of infrastructure, then you kind of always do things a certain way. And you’re like, ‘Oh, that’s how we do it.’ And you’re not realizing, ‘What’s the meaning of this?’ So it actually does force you to think about things.”

The community is reconsidering some of its practices right now. Schwall said the leadership team is considering buying a building for the synagogue — especially now that events regularly overflow rental spaces. Members do not pay dues, so making such a purchase could be a challenge. The organization is currently funded by private donors.

“We have to watch our finances,” he said. “But if the opportunity pops up, we would definitely consider it.”

Services are also taking a different tone with the involvement of Fenster, an architect who grew up in London and moved to Beijing in 2015. Schwall says Fenster has invigorated the community’s services, especially for families and their children, with his cantorial skills — making him a worthy inheritor of the tradition set by the community’s longtime rabbi, Ephraim Ferdinand Einhorn, who is now 102.

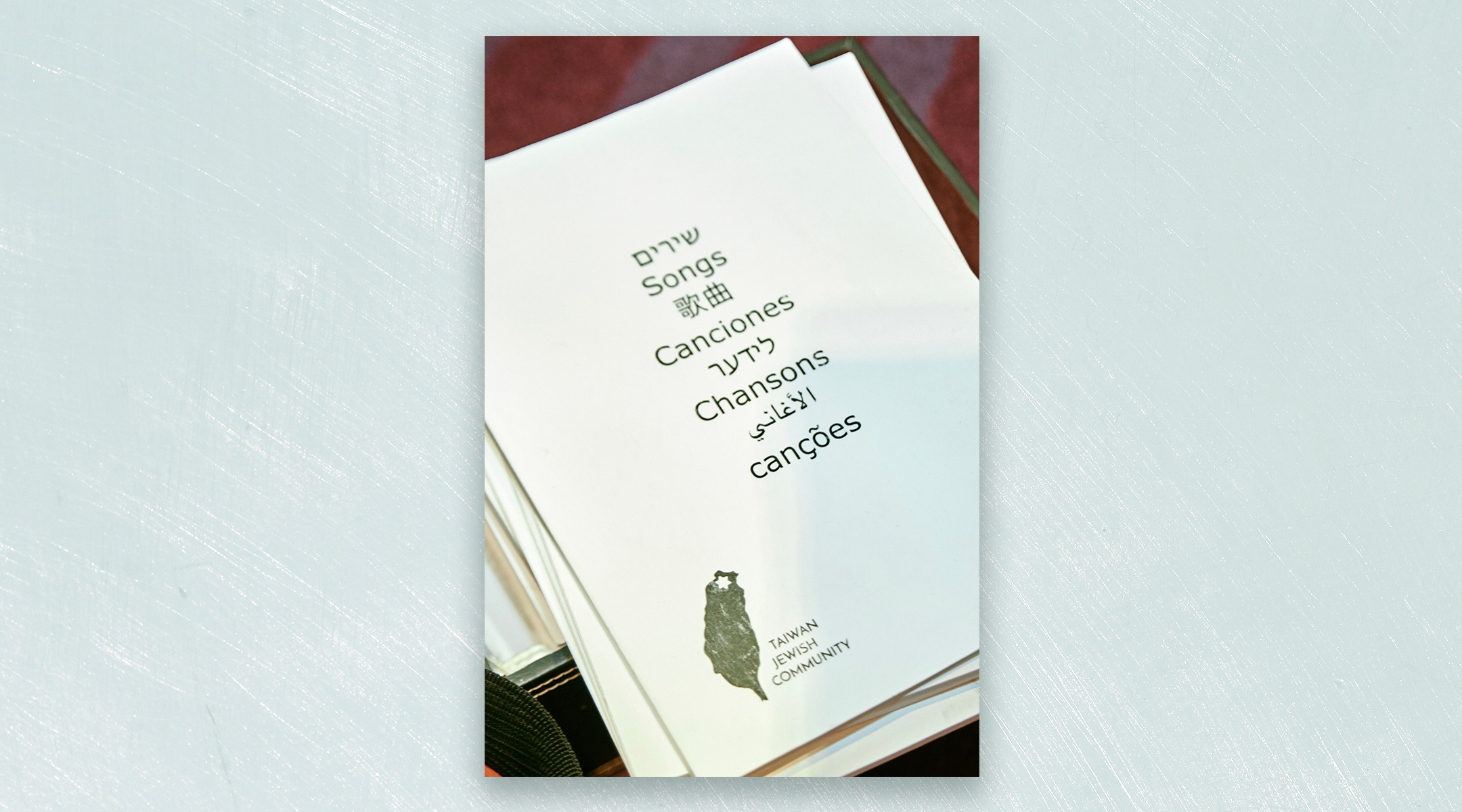

A song sheet shows several different languages represented. (Archi Chang)

Einhorn — who was born in Vienna, educated in Europe and ordained in London — is a direct tie to Taiwan’s Jewish past. Following a defense treaty in the 1950s between the U.S. and Taiwan, American military and government workers arrived. In subsequent decades, more international business flowed into the country, bringing a small number of Jewish businessmen with it. The Jewish community functioned in small spaces in the Taipei suburbs until the 1970s, when Nixon’s rapprochement with China put the U.S. relationship with Taiwan up in the air.

But even as American government infrastructure faded — the U.S. does not have an official embassy in Taiwan, in a nod to China’s claim to the island under a complex “one country, two systems” of government — several Jewish families decided to stay, and the Taiwan Jewish Community registered with the government as an official group in 1977.

Einhorn moved to Taiwan for business in 1975 and began running a minyan, or prayer group, of businessmen that met in a Taipei hotel. His group merged with the Jewish Community in the 1990s, when Taiwan’s economy shifted from some of its traditional industries, such as garment and shoe manufacturing. He ran services for decades until health problems required him to stop, but he continues to attend services and events.

Over time, the community has also been a haven for a few Taiwanese converts to Judaism, such as Zoy Chang, who joined in 2005 and converted in 2012. She noted that Taiwanese people, like many East Asians, have a positive stereotype of Jews as “very smart and very rich.”

But Chang, formerly a Christian, was drawn to the religion first.

“One of the reasons I quit Christianity is because the pastor only told me to pray — if you’re not doing good, you need to pray more about this,” she said. “But if I have a question to ask a rabbi, the rabbi will tell me how to get my answer or tell me where you can find one … Maybe, in the end, I cannot really get [my] answer … But I think that the process is [the] best.”

The group’s events have taken on a party atmosphere. (Archi Chang)

A notable member of the community is Don Shapiro, the uncle of former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Dan Shapiro, who has lived in Taiwan for over 50 years. At 77, Shapiro has become the community’s unofficial historian, writing a short chronicle of the community, which he chaired in the 1980s and 90s.

Shapiro said he was drawn to Taiwan by the food, which he first tried in New York City when he was an undergraduate at Columbia University.

“I just got fascinated by the [Chinese alphabet] characters and wanted to learn more about them. When I got to Taiwan, I found that the food here was even better than what I had imagined back in New York, and there’s quite a variety,” he said. “So it means I put on a little bit of weight over the decades. But I’ve enjoyed some excellent meals.”

Shapiro said he stayed after retiring as a journalist for Time magazine and The New York Times because of the positive experiences he had, including as a Jew in the country.

“People in Taiwan are some of the nicest people in the world,” he said. “And they really respect their foreign guests.”