The Soviet hunt for the Chabad underground: “The Great Escape From Lvov to Poland”

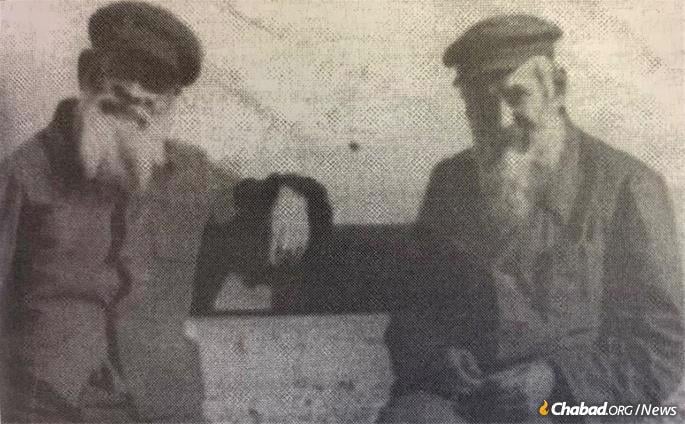

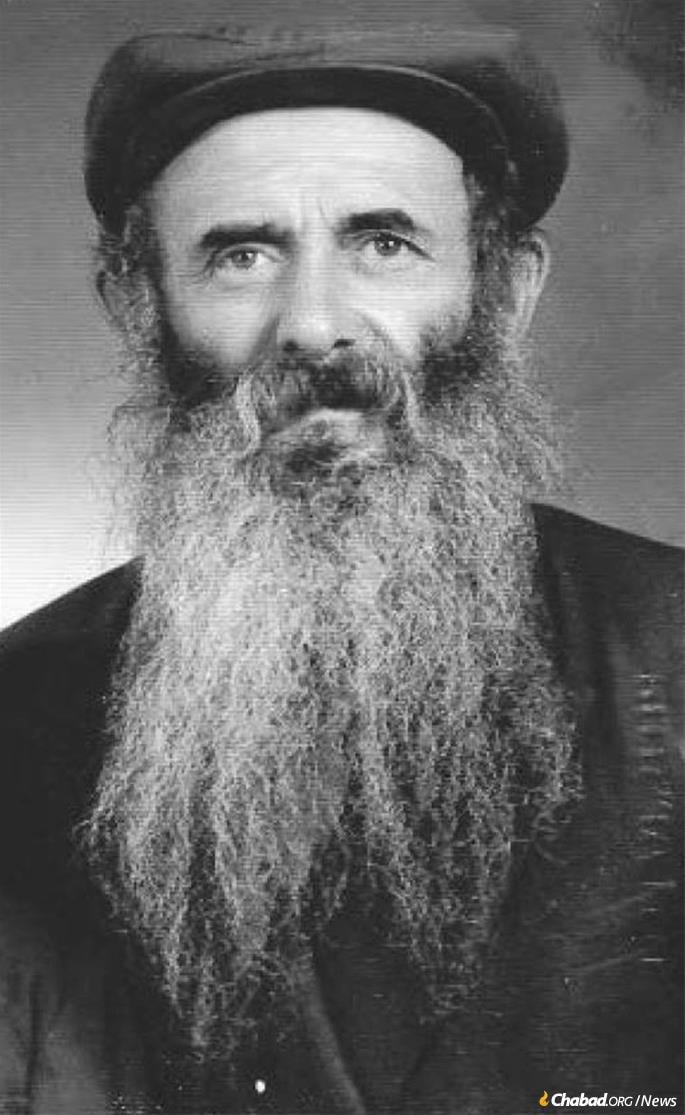

Moshe Chaim Dubrowski (right) with Berl Rikman, a Lubavitcher Chassid arrested around the same time as he was, in a labor camp.

Published September 12, 2022

This is part 2 of 3 detailing the story of the Soviet hunt for the Chabad underground. Part 1

In the beginning of 1946, a 22-year-old yeshivah student named Leibel Mochkin arrived in Lvov to scout out the town. With the help of his older brother, Shmuel (Mulle) Mochkin, and former Latvian-Jewish parliamentarian Mordechai Dubin, by then in Moscow, he connected with the chairman of the Lvov Jewish community, who in turn opened doors necessary for the operation’s success.10 The first trickle of Lubavitchers arrived in Lvov in the spring of 1946 and slowly began crossing the border. Their success encouraged others. As the months went by more and more Chassidim arrived in Lvov, abandoning their jobs, homes, furniture and any other immovable wealth for the chance to get out.“The situation was becoming desperate, with a severe shortage of food and accommodation,” Moishe Levertov recalled.“

Officially, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, it was illegal to stay in the city for more than 24 hours or to receive food coupons without being registered as a resident. To obtain registration papers, one needed a work permit. Worst of all would be if anyone were stopped by a policeman without appropriate documentation. Since the situation was so dangerous, everyone clamored to be on the first [train] that would become available.”

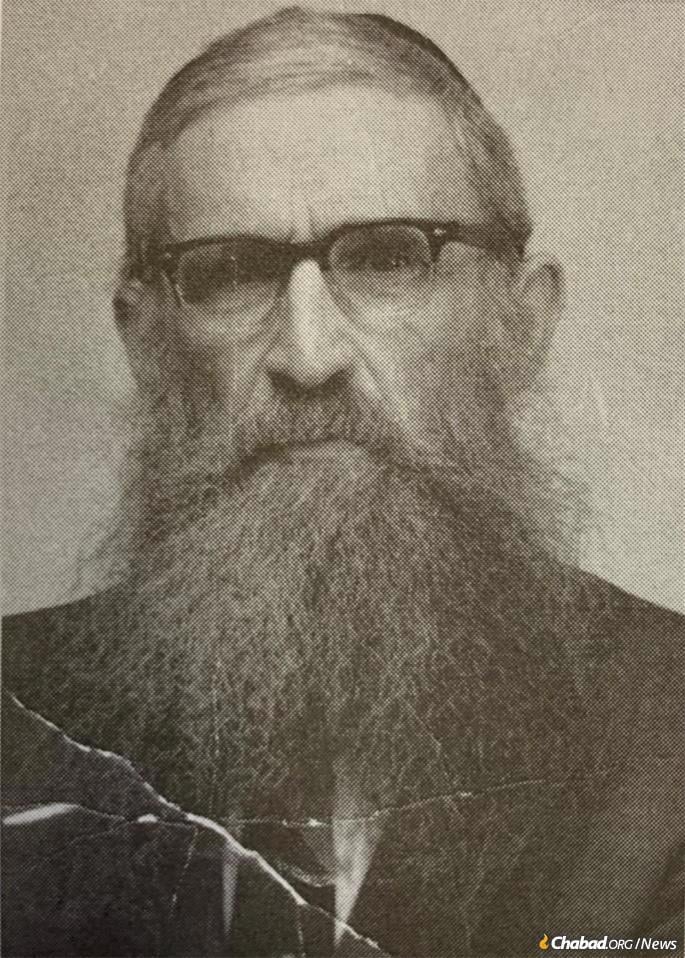

It was no longer a matter of procuring a handful of false passports, but hundreds, and a larger and more complex escape infrastructure quickly came together. Its leaders learned to doctor passports, arranged phony marriages, and of course bribed necessary officials, including those who worked at the train station and officers of the local MGB.With matters of life-and-death at hand, a specially formed rabbinical court of 23 judges was convened.11 The judges12 determined that everyone participating in the operation had to contribute whatever money or valuables they had to the pot to assist as many people as possible to leave. One of the members of the smaller operating committee leading day-to-day operations (as well as a member of the rabbinical court) was Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, whose story we’ll return to shortly. Dubrowski’s grandson, Berel Dubrowski, was about 17 or 18 at the time.

“I didn’t have a beard yet [and therefore less conspicuous], so I was sent to collect money from people … ,” recalls Dubrowski, 94. “I remember one time I needed to pick up money from someone. How do you do it? We made up he’d be sitting in the park on a bench holding a particular newspaper with a briefcase next to him. I came up to him and we exchanged briefcases, his was filled with cash, and mine had more newspapers.”

He was at various times also charged with distributing forged Polish documents. Once he was tasked with arranging a truck to bring a number of families to the train station in the middle of the night. Things nearly went south when the truck headed to the wrong place, leading to a Soviet sentry overhearing a member of the group speak Russian, a red flag that they weren’t in fact Poles. Dubrowksi followed the sentry into his post. “I asked him: ‘How much do you want?’ and he said ‘700.’ I told him, here, I have 300 in my pocket, 200 for you and 100 for your friend,’ he said ‘Okay.’ ”13

Leibel Mochkin was in charge of arranging fake Polish passports, Kahan and Futerfas handled the money, and the elder Dubrowski dealt with various emergencies. Another active member of the smaller operating committee was Tzipa Kozliner.14 Ultimately, combining Divine assistance, cunning, wits and a healthy dose of bribes, the operation successfully transplanted the nucleus of the surviving Lubavitcher community from Russia, where it had always been, to the West and Israel. That the transports were made up of visibly Chassidic men, women and children, none of whom spoke a word of Polish, is all the more startling.

By far the most prominent person brought out of the Soviet Union in this way was the Rebbe’s mother, Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson.15 The single largest illegal transport arranged by the Chassidim from Lvov left on Dec. 2, 1946 (9 Kislev, 5707), all together numbering 232 people.16 Kaganovitch estimates that only about 1,500 Soviet Jews escaped illegally using false Polish documents during this period. The vast majority of them were Chabad Chassidim.

In Poland, the Chassidim connected with members of the underground Bricha (B’riha), a Zionist organization that smuggled Jewish Holocaust survivors into British-controlled Palestine. “The B’riha men were amazed at [the Lubavitchers’] ingenious escape from Russia and deeply impressed by the discipline, the sense of solidarity and the reverence for their Rebbe in New York which held the Hasidim together,” recalled former Bricha commander Ephraim Dekel. They were secretive, he notes, and cooperated with the Bricha strictly on their own terms. “The ‘Lubavitchers’ were, in fact, running an underground network of their own … .”17

Among the Chabad leaders arrested in the operation’s aftermath were Mendel Futerfas (arrested on the train leaving Lvov in 1947, released from the Gulag in 1956); Yona Kahan (“Poltaver,” arrested in 1948, died in the Gulag in 1949); and Mordechai Dubin (arrested in 1948, died in Soviet custody in 1957). Not named in this memo but arrested on the same train as Futerfas was Shmuel Notik (“Krislaver”), previously a beloved Chassidic mentor in Chabad’s underground yeshivahs throughout the USSR, who perished in the Gulag in the beginning of 1949.18

The Second Attempt: The Chernovtsy-Romania Plan

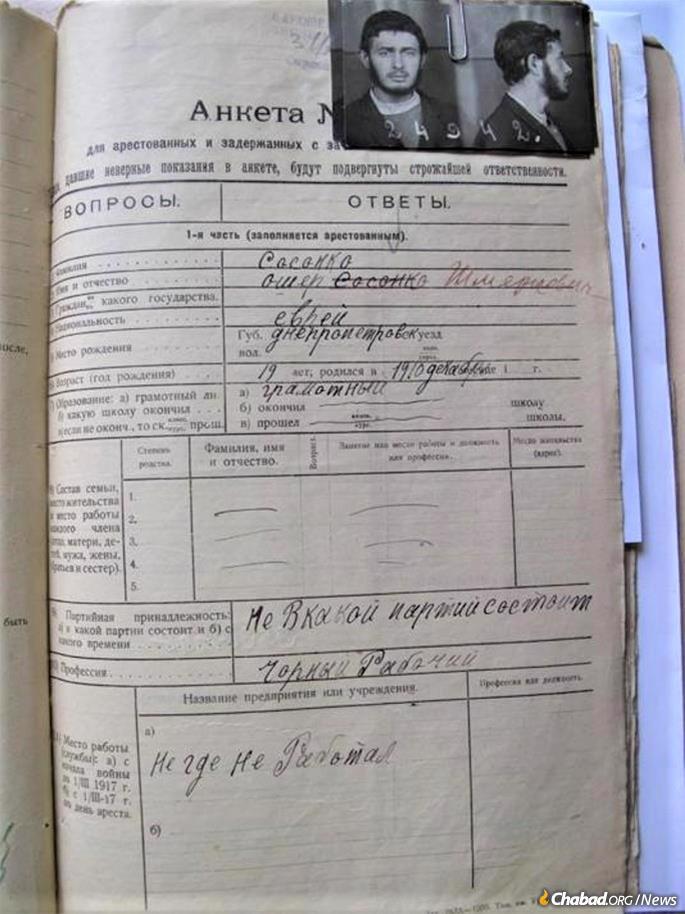

Following the end of the Great Escape, a number of Chassidim decamped to the city of Chernovtsy, Soviet Ukraine, which prior to 1940 had been a part of Romania, and before that the regional capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Bukovina region.19 Though now firmly within the expansionist borders of the Soviet Union, Chernovtsy was still close to the Romanian border, and Chassidim who had been involved in the initial escape through Lvov, namely Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, Moshe Vishedsky, Chaim Zalman Kozliner, Asher Sossonko and others, had heard it was feasible to illegally cross from there into Romania. This was by no means a fantasy. Between February and April 1946, 22,307 Jews illegally immigrated from Chernovtsy province into Romania, a process authorized by Stalin himself and organized by Soviet authorities. “… [T]he decision was not motivated by concern for the suffering of the Jewish population,” the historian Mordechai Altshuler notes. “Rather the decision appears to have been primarily influenced by consideration for the hostility of the local population toward the Jews [returning to their homes and towns following the Holocaust] and the general tendency to Ukrainize areas that had been annexed to the Soviet Union.”20

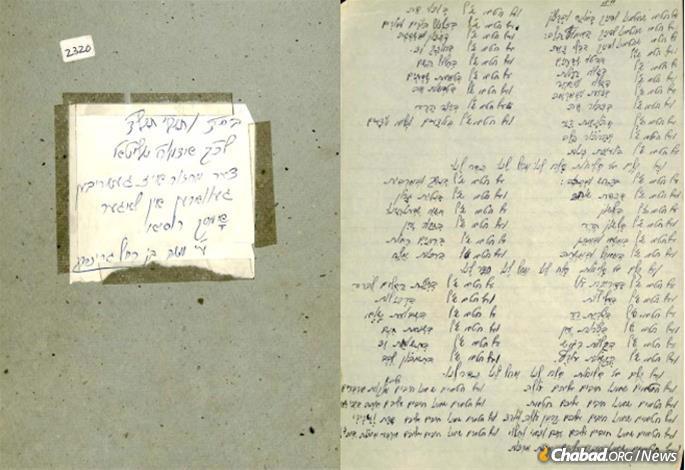

The Chernovtsy-Romania pipeline appears to have remained viable past the middle of 1946. In July of 1947 Chassidim in the USSR sent a coded message21 to Yitzchak Goldin, a Lubavitcher escape coordinator based at the time in Prague, Czechoslovakia, laying out the idea and requesting that someone be sent to Bucharest, Romania, to help coordinate an escape from the other side of the border.

Ultimately, a young Moscow-born yeshivah student named Zalman Abelsky was dispatched to Romania. Like most Lubavitcher Chassidim in Europe at the time, Abelsky had escaped the USSR via Lvov in 1946, and his starting point was the Displaced Persons camp in Pocking, Germany. He headed first to Prague where with the Bricha’s help he crossed into Austria. It proved impossible to move further so he returned to Czechoslovakia and from there crossed illegally into Hungary, reaching Romania months later. There he connected with the Skulener Rebbe, Rabbi Eliezer Zusia Portugal, who directed a network of orphanages for Jewish children in Bucharest and served as a heroic Jewish leader in Communist Romania. Abelsky was also aided by Yaakov Griffel, a war-time Orthodox Jewish activist who represented the Vaad Hatzalah, Agudas Yisrael and the Central Orthodox Committee. The MGB memo prominently mentions both the Skulener Rebbe and Griffel.

In December of 1948, 17 months after the idea was first broached, three young yeshivah students—Meir Junik, Yaakov Lepkivker and Moshe Greenberg—set out over the border into Romania with the intention of testing out the escape route before a larger-scale flight was attempted.22 At the last minute, Dubrowski, a widower in his upper 60s or low 70s, decided to join them as well. All of them were caught by Romania’s new Communist authorities and handed back to the Soviet Union. They were brutally interrogated, convicted of treason and sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment, the harshest punishment on the Soviet books at that time.23 Lepkivker would later recall his interrogator telling him they were lucky there was no official death sentence for they would have otherwise received it.24

The three younger convicts would have their sentences commuted during the post-Stalin amnesty, the charge of treason being re-adjusted to illegal border crossing. Junik, Lepkivker and Greenberg were all released in late 1953 or early 1954, and eventually allowed to leave the USSR.25 Dubrowski, on the other hand, was held for longer. The aforementioned Mulle Mochkin, who was arrested in 1951 as part of a separate case and spent time with Dubrowski in the Gulag, traveled to Siberia not long after his own 1958 release to visit his still-imprisoned friend. The shocking sight of Dubrowski’s physical deterioration left a life-long impression on him. Dubrowski was finally released sometime in 1959, but died shortly after returning to Chernovtsy.26

There is one more tragic detail. It was not, as the MGB document below asserts, four Chassidim caught crossing the border, but five. The fifth was Dubrowski’s 15-year-old grandson. Following the drowning death of Moshe Chaim’s son-in-law some years earlier, Dubrowski had taken in his two grandsons, Berel and Yehuda, and raised them as his own. Back in Lvov, Moshe Chaim had been particularly worried for the Jewish education and spiritual well-being of his teenage grandson Berel, and made sure to get him on a train out of the USSR.27 The younger grandson, however, remained with him. When Moshe Chaim chose to join the trek into Romania, he took Yehuda with him. At the time of their arrest, Yehuda was taken into custody and placed in a Soviet state orphanage.

It was decades before Berel Dubrowski managed to find his younger brother, by then known as Yura. Berel learned that his brother had gone on to serve in the Soviet army after which he settled in Chernovtsy. They exchanged letters over the years, but never saw each other again.28