BOSTON (JTA) – On an unseasonably warm December night earlier this month, some 12,000 people flocked to Boston Common for the lighting of the city’s official Christmas tree: a majestic, 48-foot white spruce.

The event marked the 50th straight year that the people of Nova Scotia supplied Boston’s tree — a tribute to how the city, led by a prominent Jewish businessman, supported the Canadian province at a time of crisis.

At the Dec. 2 festivities, recently sworn-in Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, who also took part in three public menorah lightings that week, was joined by Nova Scotia Premiere Tim Houston. The pair were accompanied by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, dressed in the Mounties’ full red regalia.

ADVERTISEMENT

Amidst the fanfare, and a concert headlined by Grammy-winning singer Darlene Love, Wu and Houston reminded revelers that the tree is a symbol of the bond between their jurisdictions that was forged during more somber times.

The Canadian province has been sending a Christmas tree to Boston as a measure of enduring gratitude for events that date back more than a century, when Boston rushed to the aid of its northern neighbors following a massive, deadly explosion in the harbor of Halifax, the province’s capital.

The fires that engulfed the city then took the lives of nearly 2,000 people, including children, and injured 9,000, with many blinded by flying shrapnel. The impact flattened swaths of neighborhood buildings and homes.

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

ADVERTISEMENT

On Dec. 6, 1917, within hours of the devastating explosion in Halifax, Abraham Ratshesky (1864-1943), a businessman, banker, politician, philanthropist and son of Jewish immigrants, was tapped by then-Governor Samuel McCall to lead the city’s relief mission.

Ratshesky organized the delivery by train of medical personnel and supplies to the port city, along with reporters from local newspapers. The mission made its way to Halifax through treacherous wintry conditions.

Vivid accounts describe a harrowing scene when a blinding snowstorm brought the mission to a halt alongside Folly Mountain in Nova Scotia. Ratshesky pleaded with the crew to persevere through their arduous shoveling, conveying the desperation of the people of Halifax.

“The men, realizing this, and knowing that every moment was precious, worked like Trojans,” Ratshesky wrote in his official report of the mission. Within an hour, the train continued on to Halifax.

Days later, two ships filled with more medical staff and supplies left Boston Harbor bound for Halifax as part of the overall relief mission. Conservative estimates put the total amount of contributions from Massachusetts at $750,000, according to Bacon.

While additional assistance soon also arrived from across the country, elected leaders and officials of Halifax especially thanked Massachusetts and Ratshesky in glowing commendations and heartfelt personal letters from ordinary citizens.

“The tree is our way of saying, ‘Thank you for being there when we needed you,’” Houston said at this year’s ceremony.

At the time, “we reached out to be of service in that moment. It’s incredible to see that bond and friendship continue to this day,” Wu said.

The tradition is about celebrating humanity and celebrating people, said Mukthar Limpao, executive director of L’Arche Cape Breton, a nonprofit disability rights organization and community residence that donated this year’s tree from their property.

“I see the generosity of Boston in 1917 as an expression of love and friendship,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in a call after the ceremony.

Known familiarly as “Cap,” Ratshesky was a leader in civic as well as Jewish communal affairs. After helping to run his family’s clothing business, Ratshesky, along with his brother, Israel, founded the U.S. Trust Company, a so-called “Jewish bank,” to provide loans to immigrants. At the time of his appointment to lead the Halifax effort, he was vice president of the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee.

His leadership and derring-do, in quickly setting up emergency medical facilities and organizing assistance, made him a hero among Haligonians (the term for people from Halifax).

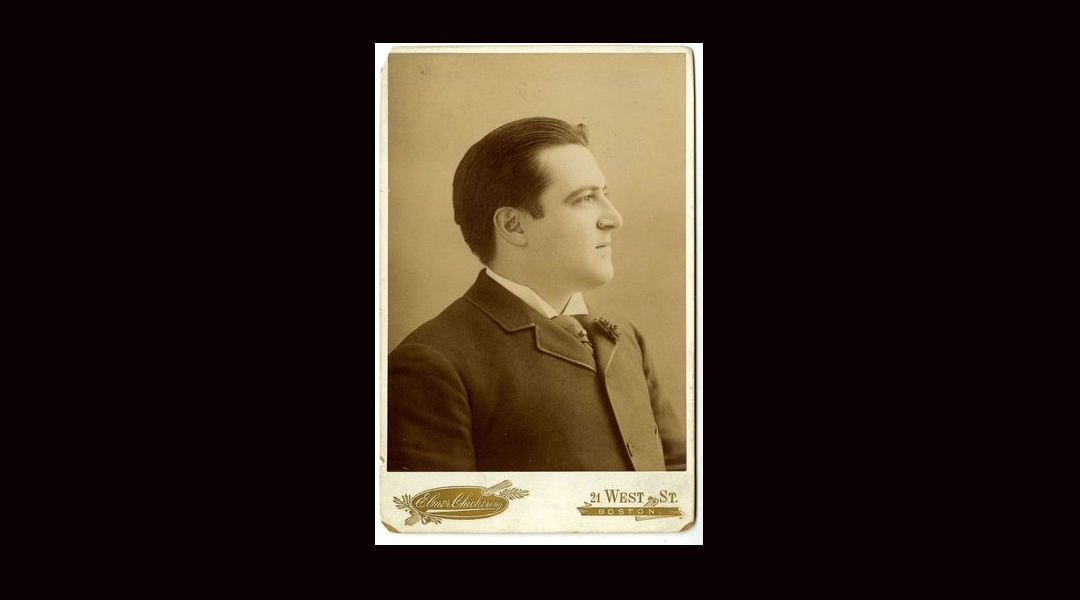

Abraham (Cap) Ratshesky, a son of Jewish immigrants and prominent member of Boston’s Jewish community, co-founded U.S. Trust Company, a bank that loaned to Jewish immigrants. (Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center)

Ratshesky “was a driving force behind this big relief effort, but his role has largely been forgotten,” said Rachel King, director of the Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The center, whose archives contain extensive records on Jewish New Englanders, houses the Ratshesky family papers – a collection which includes a worn and yellowed family scrapbook of news reports, letters and other memorabilia related to the Halifax mission.

Researchers, including John Bacon, author of the 2017 history book “The Great Halifax Explosion,” mined the archives in the run up to the centennial of the explosion, King said.

“It does seem that when people delve into the explosion, they find their way to Ratshesky’s name. He was the right man at the right time, but his name has fallen away in general,” she noted.

Among the items in the archives is a letter from a Haligonian named Walter Hoganson, who lost family in the explosion. In his gratitude, Hoganson referred to Ratshesky as “the hero of dear old Halifax” for helping the injured and homeless.

Following the explosion, Ratshesky continued to be an active presence in public affairs. During World War I, Ratshesky was assistant food administrator for Massachusetts. From 1930-32, he served as U.S. Minister (Ambassador) to Czechoslovakia, which awarded him the Order of the White Lion First Class, the country’s highest honor.

Within the Jewish community, he served as president of the Federated Jewish Charities, the precursor to the Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston, and was an early founder and supporter of the city’s Beth Israel Hospital. The Jewish Advocate, Boston’s Jewish newspaper, noted his death in March 1943 with glowing tributes.

Jonathan Sarna, the Brandeis University professor of American Jewish history and the author of “The Jews of Boston,” compares Ratshesky to another generosity-minded Jewish Bostonian: Aaron Feuerstein, the recently deceased “Mensch of Malden Mills” known worldwide for continuing to pay his workers after his factory burned down in 1995.

“They reflected a generosity of spirit at a time when it made a great difference,” Sarna said.

The tragedy and the sense of gratitude for those who helped are deeply rooted for Canadians, according to Rodger Cuzner, Canada’s consul general to New England. Growing up in Halifax, he learned about the explosion as part of the standard grade school curriculum. “I doubt if there’s anybody in Nova Scotia and most of Canada that isn’t aware of both,” he said.

Yet Cuzner had no recollection of hearing about the role Ratshesky played.

The explosion, and the annual Christmas tree, have long affected Halifax’s Jewish community, as well.

As early as the mid-18th century, there were approximately 30 Jews settled in Halifax, according to a history of the city’s first synagogue, the Starr Street Shul (known today as Beth Israel). By 1917, as Halifax became a hub of commercial and military life, it attracted more Jews alongside other immigrant workers, Bacon wrote. The synagogue was damaged beyond repair in the explosion, though its Torah scrolls were spared.

Mark David, a lifelong Jewish Haligonian and admitted local history buff, had his interest in the explosion sparked after growing up within walking distance of it. He attended the 100th anniversary commemoration in Halifax in 2017.

“I wanted to be there when they rang the bell at the exact time of the explosion,” he said. “It was a very powerful experience.”

The Christmas tree “is a wonderful way of giving back,” he added. “The people here are very proud of that tradition.”

David was unaware that Ratshesky was Jewish, but has since read about his role.

“It’s an interesting story and should be told. Even if he was not representing the Jewish community, that a Jewish person led such an important effort would be a point of pride,” he said.

Today the A.C. Ratshesky Foundation, founded in 1916, continues its philanthropic giving. It has been led by successive generations of family members – though Ratshesky and his wife, Edith, had no children. Descendant Rebecca Steinfield took over the foundation from her father, Alan Morse, in 2019, after serving on the board for a number of years; Ratshesky was the brother of Steinfield’s great-grandmother.

Steinfield does not recall hearing about the connection between her family and the Christmas tree when she was growing up, she told JTA. But as an adult, she traveled to Halifax with her father, who was interested in learning more about the family history. They met with the man whose job it was to select the trees, she recalled.

Intrigued, Steinfield read an early book about the explosion, “The Curse of the Narrows,” by Laura MacDonald. “I was fascinated by the circumstances, the role of the Red Cross, and the role of Cap,” she said.

Ratshesky “paid enormous attention to the way in which he could contribute to the well-being of his community,” Steinfield said.

She’s touched by the enduring tradition carried on through the gesture of the tree.

“We are all very different now and yet this sense of gratitude has continued. There is something incredibly beautiful about that,” she said.

“I am very proud someone in my family played a role in that.”

—

The post The little-known Jewish origins of Boston’s annual Christmas tree tradition appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.