The earliest known American Jewish novel introduces an early feminist voice

Published November 19, 2019

(JTA) — More than a century after her death, Cora Wilburn is having her moment.

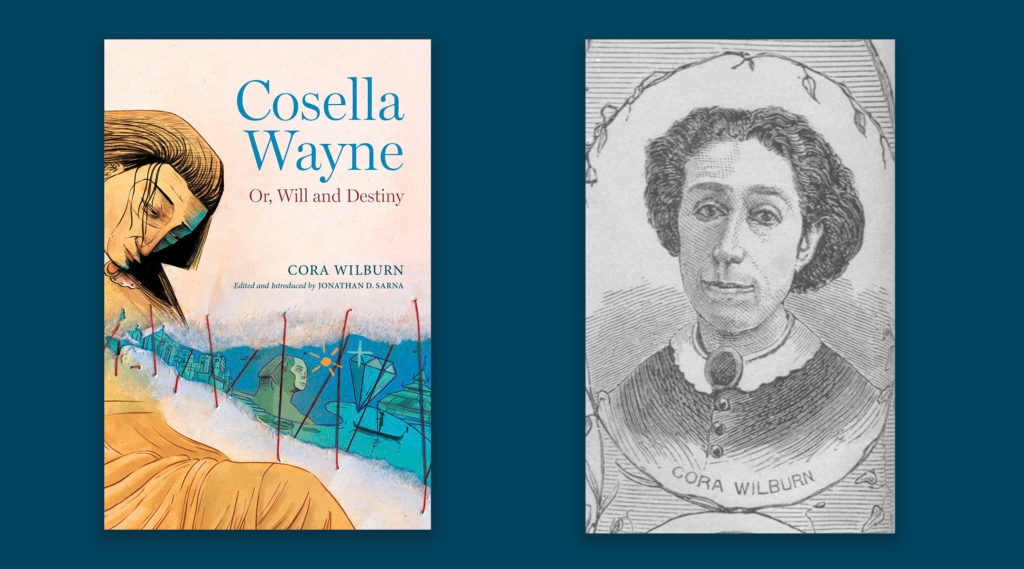

With the rediscovery and recent publication of her novel “Cosella Wayne: Or, Will and Destiny,” edited and introduced by Jonathan Sarna, the 19th-century writer nearly lost to history is being given her due as likely the first Jewish author to pen a distinctly American Jewish work of fiction.

ADVERTISEMENT

Originally published in 1860 in serialized form in “The Banner of Light,” a journal of the Spiritualist movement, this is the first time that “Cosella Wayne” has been published in book form. It’s accompanied by excerpts from one volume of Wilburn’s diary that Sarna, a scholar of American Jewish history, unearthed in the course of his research.

The revealing novel, which mirrors Wilburn’s often heartbreaking life, pulls back the curtain on subjects unknown in Jewish literature of the time: domestic abuse, women’s rights, religious and spiritual exploration, and class divides within the American Jewish community of the mid-1800s.

In the novel and her diary writings, Wilburn (1824-1906) emerges as a fiercely independent and bold Jewish thinker, an abolitionist and a feminist. Her writing also sheds light from the perspective of a Jewish woman on the early years of Spiritualism, the religious movement popular during the Civil War that encouraged communication with spirits of the deceased.

The novel, published last month, “redates American Jewish literature,” said Sarna, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University.

Until now, Sarna said, the first American Jewish novel, “Differences,” published in 1867, was credited to Nathan Mayer. Emma Wolfe, whose novel “Other Things Being Equal” was published in 1892, was believed to be the first Jewish woman novelist.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Cosella Wayne” is a melodramatic, riches-to-rags coming-of-age story of a young Jewess subjected to abuse by an unscrupulous, mean-spirited Jewish merchant, who masquerades as her father through trickery and deception. But the book also is a story of resilience, about a single Jewish woman left in poverty who stood firm in her deeply held religious and moral convictions.

While the novel depicts a devastating image of the Orthodox Jewish merchant, Wilburn’s portrayals of Jewish ritual and holiday observances are rendered with warmth and sympathy, Sarna said.

Wilburn, who later changed her name, was born Henrietta Pulfermacher, likely in Alsace, France. Her father, a conniving Jewish gem merchant, was an alcoholic and abusive. He would remarry after the death of his first wife, whom he also abused. Adopting various identities, he lived on the run across the globe, dragging his wife and daughter with him.

The experience provided the multilingual Wilburn with a rare, intimate lens of Jewish communities in Germany and in far-flung locales including India, Australia and Venezuela. Her keen observations, woven into the novel, read like a global Jewish travelogue.

Following the death of her father in La Guaira, Venezuela, Wilburn was left without means, her life upturned. Known still as Henrietta, she relocated in 1848 to Philadelphia, where she toiled as a meagerly paid, sometimes cruelly treated seamstress in the homes of the city’s well-off Jewish families, in humiliating scenes that play out in the novel.

Her vivid descriptions, both in the novel and her diary, totally changed Sarna’s view of Jewish life in 1800s Philadelphia, he said.

“Almost everything we know is from the perspective of these wealthy Jewish families …That has shaped our image,” Sarna said. “Suddenly we have a different and devastating perspective. It’s not to say one is right or one is wrong,” but it’s a reminder that there was another view, from the perspective of the seamstress.

After four tortuous years, Wilburn ended her domestic work, changed her name to Cora Wilburn and embraced a literary life, producing an “astonishing” body of writing, from poetry to essays and fiction, Sarna found.

In 1869, disillusioned with Spiritualism, she publicly reaffirmed her Jewish faith, comfortable with the tenets of Reform Judaism that was open to the liberal causes she supported.

During these later years, when she was living in poverty in Massachusetts, Wilburn wrote extensively on Jewish themes and subjects. Her meager income was supported by a few Jewish institutions and rabbis, Sarna learned. She corresponded with Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah, and had visits from the Boston Jewish writer Mary Antin.

“There’s something very exciting for a historian about discovering not only a person but a world and a text that nobody has ever known before,” especially when these are primary sources, Sarna said. “Now I hope … over time, people will study it.”