Telling the forgotten story of Osnat Barzani, the first female rabbi who lived 400 years ago, is a win for Mizrahi representation

Published February 10, 2021

This essay originally appeared on Kveller.

A week ago, I was sitting in bed working on the questions for my interview with Sigal Samuel about “Osnat and her Dove.” Samuel’s new illustrated children’s book is about the first female rabbi in history, Osnat Barzani, also known as Asnat or Asenath Barzani. I had never heard of Barzani, having always been told that German Jew Regina Jonas, who was ordained in the early 20th century, was the first woman rabbi.

But centuries earlier, Osnat was born in Kurdistan in 1590. Her story is an astounding one — she was the daughter of a yeshiva leader from Mosul, Rabbi Shmuel b. Netanel Ha-Levi. Osnat inherited her father’s curiosity about Judaism and convinced him to teach her to read and let her independently study the Jewish religious texts. She was considered to be a master of Torah, Talmud, Midrash, Kabbalah and Hebrew. After the deaths of her father and husband — who was a student of her father, and who married her under the condition that she not be bothered with housework and be allowed to continue her studies — Osnat was made the head of the yeshiva and given the title tanna’it, a rabbinical title that is equivalent to the one her father carried (tannai).

Information about Osnat is scarce. Most of it comes from a few letters, manuscripts and wonderfully enough, Jewish amulets that tell of her supernatural powers. According to the Jewish Women’s Archive, these included “her ability to limit her childbearing to two children so that she could devote herself to her studies.” (Love this 17th-century take on birth control!)

As I was low-key obsessing about this enchanting story, my 2-year-old son crawled up on the bed for his favorite pastime, Jumping on Ima. But upon noticing the book open on my computer screen, he commanded me to read it.

Reading to your child is one of the greatest joys of parenting, so of course I acquiesced. Yet this time he asked me to do something I had never done before.

“Sing it, Ima,” he ordered.

Being the sucker parent that I am, I sang.

At first I thought singing the words sounded like a verse from “Hamilton,” or maybe from a Dave Malloy musical. But then I realized the rhythms and intonations sounded more like davening to me and recognized I was chanting the book like a religious Jewish text.

The poignancy of the moment struck me. Here I was, reading perhaps the first book centering on a Jewish leader that my son has ever been read, and it was about a female Mizrahi rabbi. My son will grow up with this story — a story I had never heard until a few weeks prior — as a natural part of the Jewish “liturgy” of his youth.

I imagined that same scene in living rooms and bedrooms across the country. I imagined a new generation of Jewish kids growing up knowing about Osnat Barzani, and it gave me a sense of profound, giddy happiness.

I have known Samuel for over half a decade now. A writer from Montreal, she was my editor at my first Jewish media job at the Forward, where she wrote about Jewish diversity and her own Mizrahi heritage. Samuel is now a staff writer at Vox’s Future Perfect, and this is her first foray into children’s books. (Her first book for adults, “The Mystics of Mile End,” is a lovely exploration of Jewish life in Montreal.)

“Osnat and Her Dove” very much encompasses the scope of her work: an exploration of Jewish heritage and mysticism; a deeply feminist but not at all didactic tale with magical prose. It’s adorned with gorgeous, vibrant gouache illustrations, full of colorful loose patterns created by the Israeli-Romanian artist Vali Mintzi.

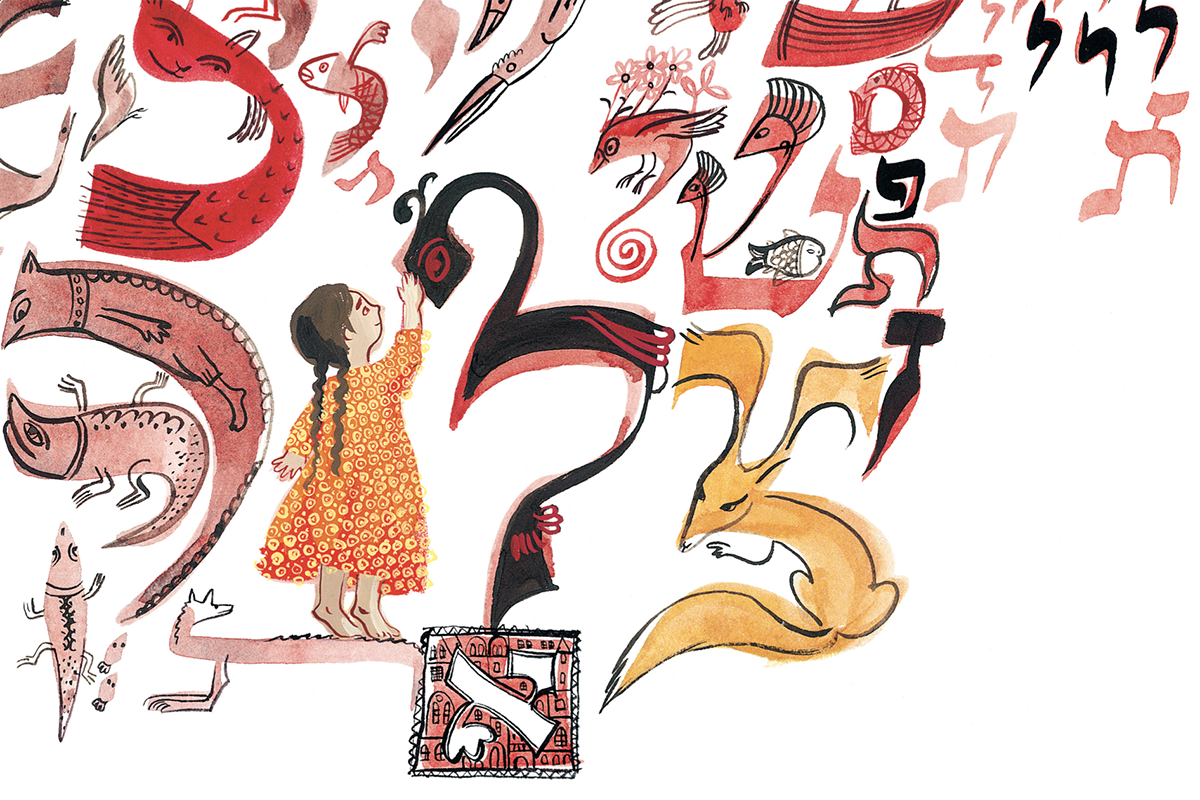

An illustration by Vali Mintzi from “Osnat and her Dove,” by Sigal Samuel.

Mintzi’s fluid brush line brings the characters to life and there’s a particularly gorgeous spread of Hebrew letters.

“Osnat loved the shapes of the Hebrew letters,” reads the prose on those pages. “One looked like a mysterious animal, and another, a creeping vine. She also loved the answers that the Torah’s words provided. Each gave rise to seven new questions in her mind.”

Just like the Torah — and any good children’s book — “Osnat and her Dove” left both my son and me full of questions. He wanted to know about rabbis, and Mosul, and to be reminded about what each Hebrew letter was. I wanted to know more about Osnat and what led to the creation of this miraculous book. Luckily I could reach out to Samuel and ask just that.

Over email, we discussed the importance of telling Osnat’s story and the value of diversity in Jewish leadership. Our conversation, which has been condensed and lightly edited, is below.

Tell me a little bit about how you came across the story of Osnat Barzani? Why did you feel like that was a story you needed to tell?

I stumbled upon the story by accident. One night, while doing research for a play about Jewish women, I fell down a deep internet rabbit hole and landed on an article about Osnat Barzani. I was stunned to learn that this Kurdish woman became the world’s first female rabbi way back in the 1600s! I’d previously thought Berlin-born Regina Jonas was the first to assume that role in the 1900s.

As a Mizrahi Jew whose family hails from Baghdad — just a few hours from Osnat’s hometown of Mosul — I was thrilled. I grew up in a Jewish landscape dominated by Ashkenazi stories and I rarely saw positive stories about Mizrahi women. It stunted my sense of what I could dare to be or become. I actually wanted to be a rabbi, but I assumed I couldn’t because I’d never seen a female rabbi who looked like me.

Kids need to see all sorts of people — not just white men — succeeding at becoming leaders. I wanted to tell Osnat’s story because it’s the story I needed when I was young, and I think it’s a story that can inspire young readers today.

There aren’t too many records available about Barzani and her life. Tell me a little bit about the research that went into making this book?

Since there were no books about Osnat, I started by reading the few scholarly articles that have been written about her. Renee Levine Melammed’s research was especially helpful. She pointed me to the few extant letters written by and to Osnat. Luckily I read Hebrew, so I was able to understand the originals.

When you read the letters Osnat wrote, you can see that she had a brilliant mind for Talmud and Kabbalah — her text is full of references. You can also see that she was a poet. Her writing is so lyrical. And when you read the letters that Osnat’s contemporaries wrote to her, you see how much they respected her. Rabbi Pinchas Hariri’s letter to her, for example, addresses her with the words “My mother, my rabbi.”

I think it’s really cool that some of what we know about Osnat comes from amulets. Kurdish people kept stories about her in there and passed them down from generation to generation.

I also did a lot of research into the Kurdish culture of the era because historical accuracy is important to me. I wanted to know exactly which instruments would have been played at a Kurdish Jewish wedding like Osnat’s, so I consulted an ethnomusicologist. I also looked at archaeological explorations of towns like Amadiya, which Osnat visited. The illustrator Vali Mintzi was committed to this research, too. She found out what sorts of clothes and customs people in Osnat’s orbit would have had.

Another Mintzi illustration from “Osnat and her Dove.”

I was honestly surprised that I had never heard of Osnat Barzani before. Why do you think so few people know about her?

On the one hand, it’s shocking that almost nobody knows about Osnat — she’s a true pioneer, the first female rabbi! On the other hand, I’m not really surprised. As a Kurdish woman, Osnat is part of Mizrahi history, and Mizrahi history has often been sidelined in favor of Ashkenazi history.

Because of this erasure, I think many of us have been trained to assume that progressive and innovative expressions of Judaism only arose in places like the U.S. or Eastern Europe. But there’s so much that was progressive and innovative in Kurdish and Iraqi Jewish cultures. Osnat’s rise to the status of a rabbi is an example of that.

The Kurdish Jewish community has such a rich history. It was obviously quite ahead of its time when it came to involving women in the study and teaching of Torah — Osnat’s story dates back about a couple of centuries before any other recorded female rabbi. Yet it’s still mostly not known by the Jewish community at large — in fact, this may be a lot of readers’ (I’m including the adults here!) first encounter with it. Is there anything you would want readers to know about it?

You’re right, it’s so rich and so little known. I find it really special that even though Kurdish society was male-dominated, it made room for intelligent women to become religious, political and military leaders. Some governed as heads of their tribe or fought as warriors. Others became poets or philosophers. This happened among Kurdistan’s Jews, Muslims, Christians and Yezidis alike. I love that not only Kurdish Jews, but also Kurds of other backgrounds, still revere Osnat as one of the first female Kurdish leaders.

Did you talk to any Kurdish Jews about what this story means to them?

The most meaningful interactions I’ve had during this whole process have been with Kurdish and Iraqi Jews, who’ve told me things like, “As the father of a Kurdish Jewish baby, thank you for writing this story!” or, “It’s so important for my daughter to see someone like her represented in books. I wish I could’ve had a book like this as a kid.”

Osnat passed away more than three centuries ago and in the last few decades, female clergy in certain streams of Judaism is finally becoming the norm. Yet there are still people who balk at the idea of a woman rabbi. Has working on this book and telling this story given you a different perspective on how far we’ve come, and on the advances we still need to make when it comes to diversity in Jewish leadership?

A lot of people think that societies become more progressive and inclusive the more time passes. But history proves that progress isn’t linear. Kurdish society in the 16th century was more accepting of the idea of a woman rabbi than some Orthodox American communities are today.

I think resurrecting a story like Osnat’s is healthy for contemporary Judaism because it can remind us that there’s no need to see female clergy as controversial. Some extremely devout rabbis in Osnat’s time were happy to recognize a woman as a rabbinic leader and we can do the same!

Who are some female Jewish leaders that inspire you?

I’m inspired by the Orthodox women who are studying at Yeshivat Maharat and graduating to become rabbis and spiritual leaders at synagogues. They are refusing to believe there’s any contradiction between being devout women and being rabbis. In that way, they’re just like Osnat. I’m also very inspired by women of color in all streams of Judaism who’ve become rabbis.

What are you hoping that young readers (and their parents/caregivers) get out of this book?

I hope young readers will learn that they can become leaders no matter what they look like or where they come from.

And I hope readers of all ages will feel inspired to learn more about the rich cultures of Mizrahi Jews — from Kurdistan to India to Yemen. As someone who’s studied Mizrahi rabbis’ writings, I’ve found it impressive that they often (though not always) express a tolerant and moderate worldview. I think they actually have a lot to teach today’s Judaism about how to honor diversity. Instead of continuing to leave them on the sidelines, let’s start putting their insights to work.

“Osnat and her Dove” is available on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.