Seeking Kin: In Salonika, preparing for a unique graduation

Published January 6, 2014

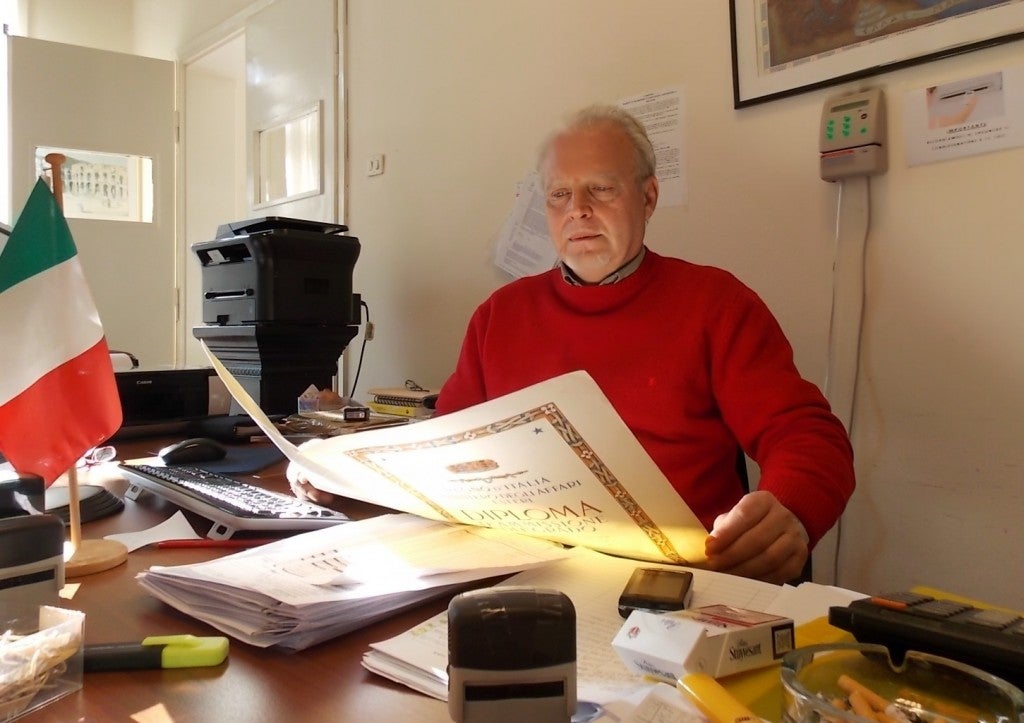

Antonio Crescenzi hopes to present the diplomas from some of the 157 Jewish pupils from the Umberto No. 1 Italian School in Salonika to the graduates or their relatives at a ceremony on January 27. (Courtesy Antonio Crescenzi)

The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Scanning the list of students, Benny Natan wondered if he would recognize any names from his youth in Salonika, Greece.

One of the 157 names jumped out: Nissim Tazartes.

Natan, a space and aeronautics professor at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, beamed. Tazartes was his first cousin, someone he had heard much about growing up but never met.

The list of children who attended the Umberto No. 1 Italian School in Salonika between the world wars was compiled by Antonio Crescenzi, an events coordinator in the city’s Italian Institute of Culture. Crescenzi had discovered middle- and high-school diplomas that some Umberto graduates apparently had never received and surmised that many of the 157 Jews among them were later deported in the Holocaust.

He hopes to locate pupils or their relatives to invite to a ceremony presenting the diplomas at the Salonika institute on Jan. 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

To publicize the search, an Athens newspaper article about Crescenzi was posted on a website run by a Greek-Israeli man. That led to mid-December mentions on “Kol Shishi,” an Israeli radio program hosted by Yaron Enosh, a Grecophile. The list also is being circulated in the 3,000-member Athens Jewish community, the 1,000-member Salonika Jewish community and Greek-Jewish groups elsewhere.

Nearly all the 157 Jewish students were born in the 1910s, so they would have graduated during the 1920s and 1930s, long before the Nazi occupation decimated Greek Jewry.

Athens resident Manon Maissa speculated that many graduates on the list merely forgot to pick up their diplomas.

That’s likely what occurred with her father, Salomone Maissa. After graduating Umberto, he attended university in Italy, joined the Greek army, returned to Salonika and was deported to Auschwitz. He survived, but his parents, Abramo and Maria, were murdered there.

Salomone Maissa married, rejoined the army, settled into a medical practice as a dermatologist and started a family.

“His priority was not to go to the school and [retrieve] his diploma,” Manon said.

Salomone Maissa died in 1992 at age 79.

The private school was one of several where well-off Salonika families sent their children in the decades between the world wars, explained Lily Eiss of Tel Aviv. Her father studied at the German school in Salonika and her mother at the French school.

Eiss described Salonika then as cosmopolitan, given the Turkish, Armenian and French names she identified on Crescenzi’s expanded list.

“For me it’s very exciting,” Eiss, whose family settled in Salonika following the Spanish Inquisition, said of Crescenzi’s search for graduates.

Nelly Arouch, who runs the Jewish youth education programs in Salonika, said that even in a small way, Crescenzi’s list will help document the individuals murdered in the Holocaust. Now, she said, only 15,000 names of the estimated 50,000 Greek Jewish victims are known.

An open window in 2003 launched Crescenzi’s effort.

At the time he was teaching history and Italian at the cultural institute, which until 1944 housed the Umberto school. One stormy day he shut one of the building’s basement windows and moved away wet cartons. He noticed a yellow paper and placed it in a carton before returning to the room several days later for a closer look.

It was a composition penned by an Umberto pupil, Alberto Modiano, titled “The Nicest Day of My Life,” on the boy’s joy when his father promised to buy him a bicycle. Another composition, by Ester Saporta, described her happiness on a family boat trip to South America in 1934. Crescenzi soon found more papers: the diplomas, tests and class registers.

In the past decade, Crescenzi said he has cleaned off, read and categorized the documents, and recently began seeking the Jewish owners of the diplomas.

Crescenzi said he became interested in Salonika Jewry because of an experience in 1992, after moving there to marry a city native he had met in his native Italy. Stopping at a water fountain in a yard off a narrow street, he noticed he was standing on a slab of marble from a Jewish gravestone. Crescenzi recalled being ashamed that it adorned the fountain.

“I was feeling that rather than standing on that stone, the same stone was pressing my head very hard. I had to do something,” Crescenzi said.

He contacted the Salonika Jewish community office and returned to the yard two days later prepared to uproot the stone himself. It was gone.

Crescenzi said he learned much by researching some of the Umberto students. One, Shlomo Venezia, was the rare Auschwitz inmate to survive the Sonderkommando units charged with cremating those murdered in the gas chambers. Venezia would move to Rome and publish a memoir before he died at 88.

Modiano was hidden during the occupation and survived; Saporta and her mother were sent to Auschwitz.

“I do not know how many times I have read the two wonderful compositions” by Modiano and Saporta, he said. “I realized that the innocent and wonderful feelings expressed in those lines came from Jewish children who … later would be obliged to handle serious matters when the war came.”

Upon locating Maissa, their telephone conversation was “very emotional for me and for her,” Crescenzi said.

Maissa said she “of course” will attend the Jan. 27 ceremony.

“After so many years, to find someone who discovered part of my father’s life and history — it’s very touching for me,” she said.

Natan, now on sabbatical in Italy, said he or his Athens relatives also will attend. His cousin, Tazartes, escaped deportation to Auschwitz because his late father held Spanish citizenship. Tazartes settled in Italy, working as a journalist under the name Giorgio Tazartes; his mother, Regina, and sister, Elsa, moved to the United States. The three have died and neither Giorgio nor Elsa had children, Natan said.

Crescenzi sees the ceremony as timely beyond the Holocaust-commemoration day, since Salonika will serve as the European Youth Capital in 2014.

“What would be better for the young people of today to remember,” he said, “than what should never occur again.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at [email protected] if you know the whereabouts of anyone appearing on the Salonika list or their relatives. If you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends, please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

![]()