Rosh Hashanah by Zoom? Synagogues are already planning for a socially distanced High Holidays

Published April 21, 2020

(JTA) — For rabbis, the end of Passover marks the beginning of a new season: planning for the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the High Holidays in the fall when Jews pack synagogue sanctuaries.

This year, that planning includes grappling with the reality that in-person services might still be impossible, depending on the course the coronavirus pandemic takes between now and then.

American synagogues have been conducting services virtually — or not at all — for more than a month. When they closed their doors, many expected that several weeks or, at most, a few months would elapse before the pandemic was under control enough for in-person religious services to resume.

But as the weeks wear on, it is becoming increasingly clear that the resumption of normal activity remains a far-off proposition. Even as a few states begin allowing some businesses to reopen, social distancing guidelines remain in place, and some city officials and public health experts have warned that large gatherings are unlikely to be safe until some time in 2021.

That leaves Rosh Hashanah, which this year begins Sept. 18, as a major question mark.

“We’re making the assumption that by September it’s not going to be OK to have a thousand people together in one room, so we’re taking that as a starting point,” said Rabbi Barry Leff of Herzl-Ner Tamid, a Conservative synagogue just outside Seattle on Mercer Island, Washington.

Leff says that in the coming months, the congregation, which has 750 member families, will be planning for a number of possibilities. That includes thinking about how many people would fit in the synagogue’s sanctuary — which can regularly hold up to 1,000 — if social distancing measures are enforced. It also means thinking about who would get to attend if the state lifts its stay-at-home order and allows smaller gatherings of people.

“If they say ‘Fine, you can have 50 people,’ how do you pick which 50 people get to be the ones that get to be there? Or do you set up a rotation, where people can sign up for an hourlong time slot? It can get very complicated pretty quickly,” he said.

Members of the media wear protective masks film outside the Young Israel of New Rochelle which was quarantined after a member was hospitalized with the coronavirus, in New Rochelle, N.Y., March 10, 2020. (Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images)

It’s too early to say for sure what things will look like in September, said Stephen Buka, a professor of epidemiology at Brown University. Whether gathering in person will be advisable depends on a number of factors, including how the country’s testing infrastructure develops and if coronavirus infections rise again as temperatures cool.

“Right now, the requirement is that everything be virtual, and I think that wouldn’t necessarily be needed in July, and it’s too hard to say what will be needed in September,” he said.

Buka says that even if High Holiday services could be held in person, they wouldn’t be the same as in previous years. Social distancing measures would likely be needed and at-risk groups could be cautioned from going.

“I think a very likely scenario to predict at this point is that if you’re over 70, don’t congregate, stay home, and that if families with young children want to come and be socially distanced that could very well be a reasonable compromise,” he said.

The rapidly changing recommendations and policies around preventing the spread of the coronavirus, which so far has killed at least 44,000 people in the United States, has some rabbis waiting to plan for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

“We’re not thinking about that yet, so I can’t tell you what’s going to happen,” said Rabbi Hershel Billet of Young Israel of Woodmere, an Orthodox synagogue on Long Island. “If this stretches out into the summer, we’re going to have to begin thinking about it.”

But many other synagogues have started planning for multiple contingencies.

Temple Rodef Shalom in Falls Church, Virginia, holds eight services on the first night of Rosh Hashanah, and 3,000 people typically spend some time in the synagogue’s three spaces. “The busiest airport in America is what our building looks like,” said Rabbi Amy Schwartzman.

With that experience seeming increasingly unlikely, Schwartzman and the four other clergy members at Rodef Shalom are holding a scenario planning meeting this week to explore other possibilities — including the fact that the synagogue may have no in-person worship at all due to the coronavirus.

“We know that in the worst-case scenario we could provide the congregation with an online worship experience for all the holidays,” she said.

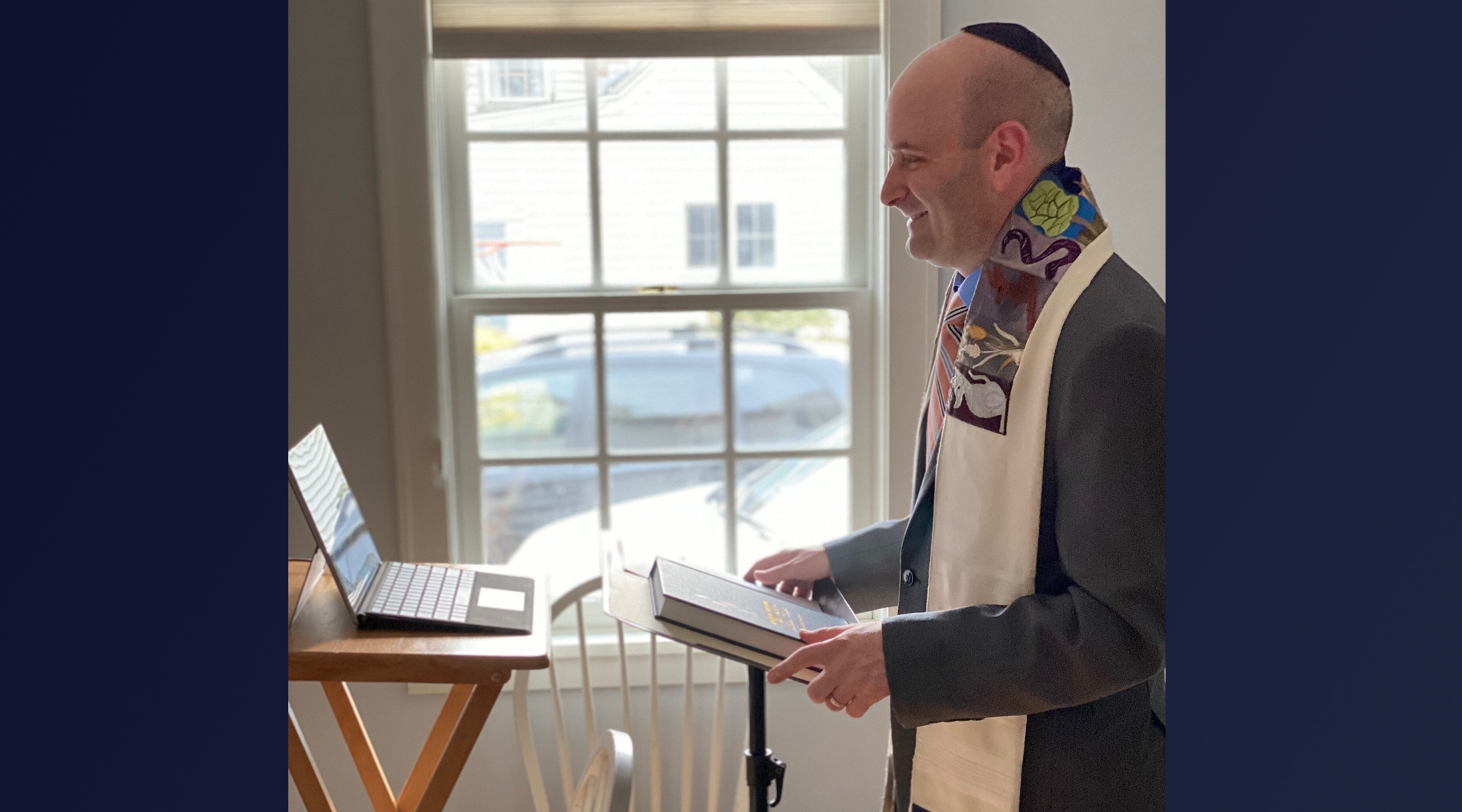

Rabbi Danny Burkeman of Temple Shir Tikva in Wayland, Massachusetts leads virtual services for his congregants from home. (Courtesy of Burkeman)

Rabbi Joshua Stanton at New York’s East End Temple has been exploring how his community might be able to do certain parts of the High Holiday rituals in person. For example, if officials allow people to gather outside in smaller groups, the Reform synagogue may be able to do tashlich, the ritual where people gather outside to throw bread in a body of water to represent casting off their sins.

“I think that we will supplement with virtual elements as much as is needed while prioritizing in-person experiences as much as it is safe,” he said.

Rabbi Robert Harris, a professor of Bible at the Jewish Theological Institute who also serves as a part-time rabbi at Temple Beth Shalom in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sent out an email to congregants on Monday soliciting their thoughts on a number of possibilities.

Harris, who made an early and bold plea to his colleagues to cease all live synagogue events in March, said he expects services to take place via a livestream. But he said he is still figuring out details such as whether members at the nondenominational synagogue will join virtually or whether a minyan, the prayer quorum of 10 people required to say certain prayers, would gather in one place if permissible and the rest would join via livestream.

“None of us are prophets,” Harris said, “but I think if we’re not planning for the eventuality that this fall we’re going to still be socially distancing ourselves, then we’re abandoning our responsibilities to our communities.”