Peter Eckstein-Kovacs has defended Jews and other Romanian minorities for decades. Will his legacy survive the Orban era?

Published May 26, 2020

SIBIU, Romania (JTA) — The former Romanian politician Peter Eckstein-Kovacs knows how to command an audience.

He has broad shoulders and a bellowing voice, which at a recent political event here, in this country’s Transylvania region, he uses to denounce all forms of bigotry and promote diversity.

When the event organizer hands him the mic, Eckstein-Kovacs launches into a speech decrying those who use the “issue of the foreigner to scare people” — a less than opaque reference to the anti-immigrant views of right-wing European politicians.

Eckstein-Kovacs adds that he has some Jewish ancestry, which with the rest of his identity has informed stances he took throughout his political career — notably as a parliament member and adviser on minority issues to the president and prime minister — and now as a private citizen.

He represents ethnic Hungarians in Romania, who make up nearly 7% of this European nation’s population (and almost 20% of Transylvania’s) at the panel. Romania’s centrist USR and PLUS parties organized the event to promote diversity in Sibiu, the former capital of the Transylvania region, as a model for the rest of Romania and Europe.

Other representatives stood in for their own communities: the Jews, Germans, Roma and even Arabs — there is one Syrian refugee who settled here in the 1990s, became fluent in Romanian and married a Romanian woman. Eckstein-Kovacs’ voice fills the room, bouncing off the yellow-painted walls, at the Biblioteca Astra Sibiu, the city’s high-ceilinged baroque library.

It’s a significant event for this part of Europe, where the anti-immigrant and autocratic policies of President Viktor Orban in neighboring Hungary echo loudly. The event is also symbolic of Eckstein-Kovacs’ position at the nexus of a range of these issues — and how he notably stands up for Romanian Jews and other minorities in a region highly scrutinized for its nationalism.

Being Jewish was a ‘way out’ of Romania

Born in Cluj in 1956, Eckstein-Kovacs endured nearly 40 years of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s unbearable Stalinism. For almost half a century, there was no talk of religion in Romania, which was effectively outlawed by the state.

“Nobody spoke about my Jewish identity,” Eckstein-Kovacs recalled in an interview with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency following the panel.

His Hungarian school listed his name only as “E. Kovacs,” glorifying the obviously Hungarian name while obscuring the obviously Jewish one that preceded it. At 14, however, he discovered his identity and asked his parents about his Jewish origins.

His father was half-Jewish, albeit not practicing. Around the time Eckstein-Kovacs posed the question, Romanian Jews were frequently disappearing without notice — largely not to gulags or prisons, but to Israel. Over 420,000 Romanians immigrated there, or made aliyah, during the communist years.

“Everybody was happy to be a Jew and to escape,” he said. “It was a way out.”

Being Jewish allowed one to secure an Israeli passport and leave behind the iron fist of communism. But Eckstein-Kovacs says he never considered immigrating to Israel — or to Hungary or Germany, countries that he says would have received him given his ethnic ties.

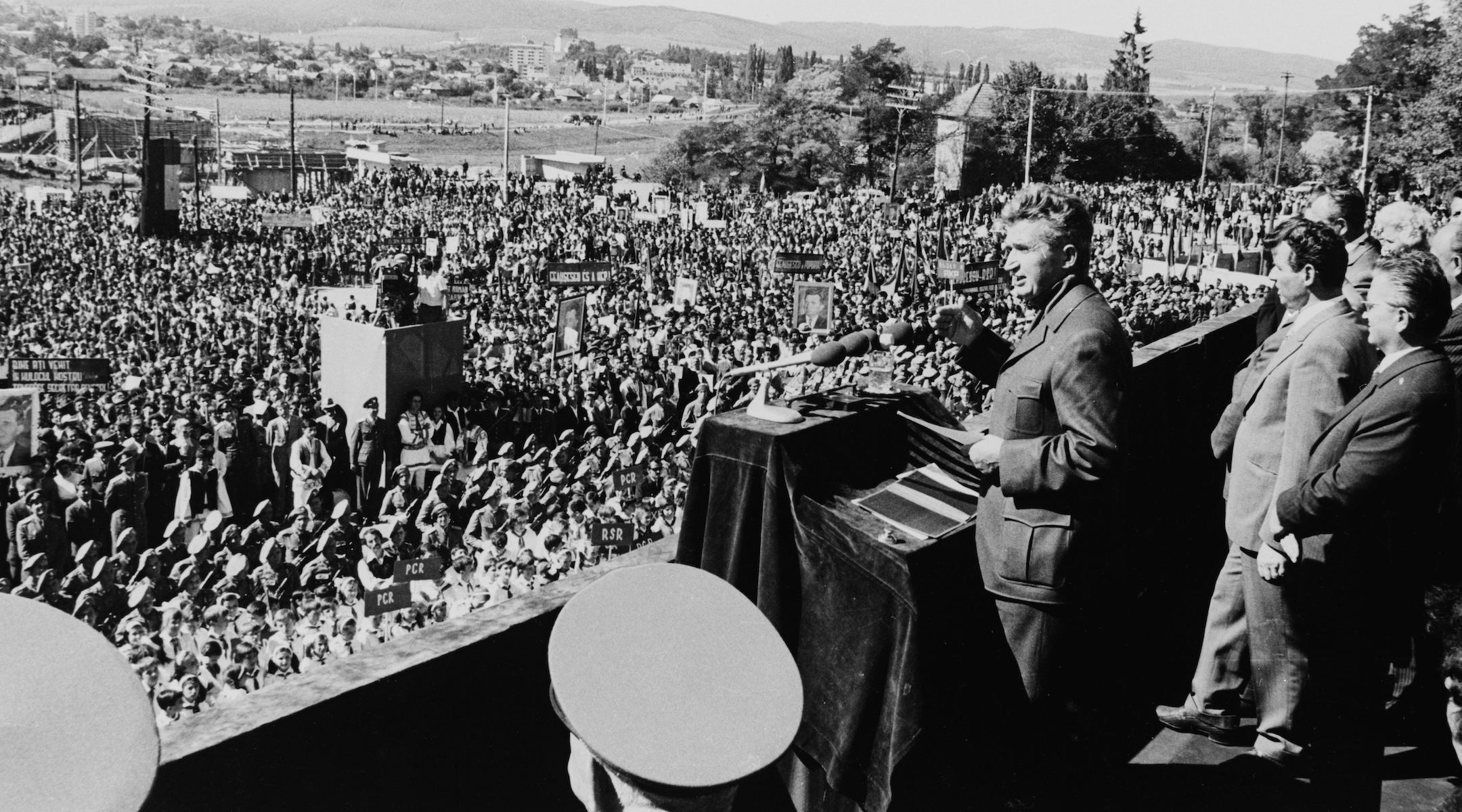

President Nicolae Ceausescu of Romania addresses a rally in Sfantu Gheorghe, circa 1975. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In explaining his decision to remain here, he told what a few others confirmed to be a classic Romanian joke: Five Romanian friends part ways as young adults, some moving as far away as Australia or South Africa. Eventually they meet again, many years later, and trade stories of their travel. And when they get to the fifth friend, they say, “Oh no, he’s an adventurer, he stayed in Romania.”

Eckstein-Kovacs is the adventurer.

“I want to live here!” he says, smiling and shrugging his shoulders.

A career of defending Jews

Despite living through the terrors of communism — he wouldn’t specify what he and his family went through — Eckstein-Kovacs has managed to make the most of Romania. He joined the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, or UDMR, after the 1989 revolution, serving as its deputy leader in Cluj until 1992, when he became a councilor for the city. He held this role until 1996, when he was elected to parliament as a senator for Cluj.

In January 1999, he joined Prime Minister Radu Vasile’s short-lived Cabinet as a minister-delegate for national minorities, serving until the administration fell in December of that year. He was reelected to the Senate in 2000 and soon spearheaded anti-discrimination legislation that was adopted later that year, for which he received international recognition.

Discrimination against the Roma people, known pejoratively as “gypsies,” is arguably as widespread in Eastern Europe as anti-Semitism. The Wilson Center, an American think tank, in 2001 credited Eckstein-Kovacs as one of the “handful of dedicated public servants sprinkled sparingly throughout this region who are working tirelessly, under the most difficult circumstances, to improve respect for the human rights of the Romani minorities in their countries.”

Meanwhile, a confidential 2005 U.S. State Department cable on “Romania’s ethnic Hungarians” echoed this assessment, noting that Eckstein-Kovacs founded several local human rights groups and “advocated strongly” for the restitution of churches and other religious properties seized under communism. The cable praised him as “a staunch advocate for minority rights” who “repeatedly criticized and opposed the actions of the former extreme nationalist mayor of Cluj.”

His liberal views eventually clashed with those of Romania’s Hungarians and their party. For example, Eckstein-Kovacs is perhaps best known for supporting LGBT rights — he’s advocated for legal partnerships for same-sex couples and appeared at Cluj LGBT Pride events, and in 2008 was named Man of the Year by Romania’s gay community. He also once even accused the center-right UDMR of being Romania’s most misogynistic party.

This earned him scorn, even bigotry. As one Hungarian online commenter put it: “Eckstein is a Jew and does not represent Hungarians.”

Eckstein-Kovacs remained in the Senate until 2008. A year later, though, he broke ground as Romania’s first presidential adviser for minorities under Traian Basescu. The UDMR had been clamoring for the position since 1990.

“I was the one who was deciding how much the president was involved in those issues — so he got very involved,” Eckstein-Kovacs said, chuckling.

Eckstein-Kovacs said he also got Basescu “very involved in relations with Israel.”

Basescu made two official visits to Israel. After meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Shimon Peres in 2014, Basescu declared that the Palestinians must recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

“He had lunch with Netanyahu once and was also involved with the Palestinians. He had dinner with Abu Mazen [Mahmoud Abbas],” Eckstein-Kovacs said proudly. “Not in the same day, but he’s friends with everyone.”

Eckstein-Kovacs served in the role until 2011, when he resigned over a proposed mining project in Transylvania that he said would threaten the environment and endanger nearby ancient archaeological sites.

After a series of subsequent unsuccessful runs for office, he resigned from the UDMR in 2018, citing the party’s “greed” and increasing servitude to Orban’s ruling right-wing Fidesz party.

Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary at a news conference in Prague, March 4, 2020. (Michal Cizek/AFP via Getty Images)

Eckstein-Kovacs has since returned to daily life in Cluj, giving up the 280-mile commute to Bucharest he made for 17 years. He’s still involved with the Tranzit House, a foundation and arts space now run by his wife, which houses “Cine îi recunoaşte? Tudsz róluk? Missing 1944-2008” — an archival project commemorating the Holocaust-era deportation of Cluj’s Jews. The remaining elderly Jews there use the foundation’s payments to support its work, such as maintaining Cluj’s other synagogue and the area’s Jewish cemeteries.

But Eckstein-Kovacs continues to speak up publicly as well: He recently accused Fidesz of trying to “convert” Transylvania’s Hungarians to adopt the party’s ideas of conservatism, illiberalism and xenophobia toward non-Europeans. Meanwhile, Romanian politics are dominated mainly by the liberal Social Democratic Party and centrist National Liberal Party.

Orban, who has used the coronavirus crisis to secure staggeringly wide-ranging powers, has been accused of rhetoric that some find anti-Semitic — particularly when it has been in reference to George Soros, the Jewish billionaire and Holocaust survivor who has promoted several liberal causes in his native Hungary.

Eckstein-Kovacs says he is devoted to pushing back against what he calls “popular anti-Semitism” in Romania. Rates of anti-Semitic incidents are low in Hungary, but some say that Orban has fostered an environment that is hostile to minorities. Several Romanian Jews told JTA that anti-Semitism here is mostly verbal rather than violent, but remains relatively widespread — an assessment echoed by six former U.S. ambassadors to Romania.

“When people speak about Jewish[sic], they talk bad about the Jews,” Eckstein-Kovacs said. “But it’s just talk. If you don’t know how to talk about people, you’ll just say bad things about them.”

He’s happy to defend Romania’s Jews even when those attacking them are Hungarians — and friends.

While serving as the presidential adviser for minorities, he was in charge of returning nationalized buildings to the minority communities to which they belonged. Many of the buildings belonged to Jews, he said, even though the overwhelming number of Romanian Jews are now in Israel. Eckstein-Kovacs still made sure the community got its buildings back.

“One of the leaders of the Hungarian party called me by phone. He complained, ‘Why do you give so many buildings to the Jews? They’re almost gone, and we exist!’” Eckstein-Kovacs said. “I told him, ‘You’re an anti-Semitic shit!’ And he hung up the phone.”

After two minutes, the Hungarian called back.

“‘How can you call me an anti-Semite when my wife is Jewish?’” he asked, to which Eckstein-Kovacs responded, “‘Well, you’re an anti-Semitic shit with a Jewish wife!’”

“He was a very good friend of mine,” Eckstein-Kovacs said. “Was.”