New York City is considering a ban on fur. Hasidic Jews and Jewish fur dealers aren’t happy.

Published June 21, 2019

NEW YORK (JTA) — It’s summer and Marc Kaufman has thousands of coats in the basement of his store in Midtown Manhattan. For a fee, the fifth-generation fur dealer cleans and stores them for his customers to help prevent heat damage.

Upstairs there are racks and racks of coats for sale — lynx, mink, chinchilla, sable and coyote, Kaufman’s personal favorite. There’s everything from a long white fox coat speckled with bright pink, black and blue to a bluish gray bomber-style chinchilla jacket.

Coats sell for an average of $3,000 but can go for up to $150,000. Kaufman has sold to big names such as Jennifer Lopez and 50 Cent, and his grandfather sold fur to Marilyn Monroe and Liberace.

But new legislation proposed in the City Council here could threaten Kaufman’s livelihood, and those of some 150 other stores in New York that earn the majority of their income through fur sales.

In March, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson introduced legislation that would ban the sale of new fur apparel.

“As an animal lover, I believe it is cruel to kill an animal just for the purpose of people buying and wearing a fur coat. There is really no need for this,” Johnson said in a statement ahead of introducing the bill.

In May, the council heard testimony from opponents and critics of the ban. Following the hearing, Johnson slightly changed his tune, saying he would want a potential ban to be phased in over time time to have a less dramatic impact on the industry.

The New York State Senate and Assembly also are considering bills to ban the sale of fur in the state.

Stores that earn the majority of their revenues through the sale of fur employ about 1,110 people, according to Fur NYC, which opposes the ban. That doesn’t include a supply chain that includes marketing, banking and insurance, says the trade group.

“A fur ban would be catastrophic to New York City — eliminating a historic manufacturing community, along with thousands of jobs for New Yorkers who’ve never made another living and millions of tax revenue that fund critical government programs that help New Yorkers,” according to Fur NYC.

Like many other stores in New York’s Fur District, there are signs posted on Kaufman’s store protesting the proposal.

“If they don’t want to wear furs, they don’t [have to] wear it,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last week. “If they don’t want to eat meat, let them not eat meat. But don’t impose your views on me.”

There are more than 150 fur stores in New York City, according to a trade group advocating against a proposed fur ban. (Josefin Dolsten)

Jews once dominated the New York fur and garment industry. The boom of the ready-to-wear clothing industry after the Civil War coincided with a large influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, said Daniel Soyer, a professor of American Jewish history at Fordham University who researches the garment industry. Indeed, Kaufman’s own family entered the industry in 1870 after emigrating from Russia, Germany and Hungary.

Since ready-to-wear clothing production was a new industry, Jews faced fewer barriers than in already established fields, Soyer said. Some Jews also brought relevant skills from their native countries.

The number of Jews working in the garment industry remained high through the 1920s (in 1910, three-quarters of the furriers in the city were Jews). It started decreasing in the 1960s with the rise of mass-produced clothing, according to Soyer.

Animal rights activists say the practice and methods of killing animals for their fur is cruel. Starting in 1992, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, began a memorable “Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur” campaign that eventually included celebrity spokespeople.

During a hearing on the proposed legislation last month, Johnson showed graphic images of animals housed and killed for their pelts. A number of celebrities, including fashion guru Tim Gunn, have spoken out with PETA in favor of the ban.

In addition to fur dealers, a number of groups oppose the proposed ban. They include members of the African-American community, for whom fur continues to be a status symbol, and some environmental activists, who argue that it will lead to an increase in non-biodegradable fake fur coats.

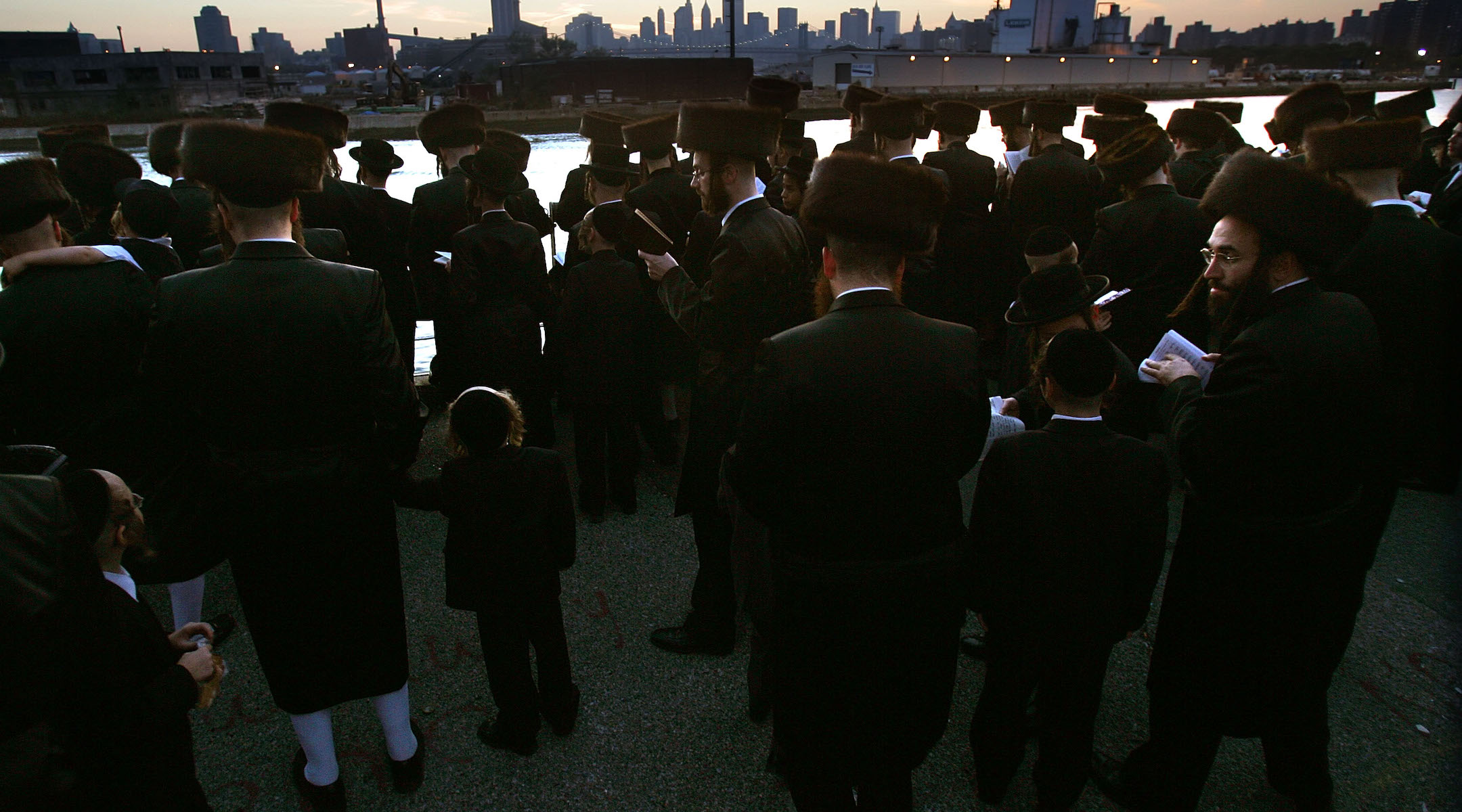

Also opposing the ban are Hasidic Jews, who often wear the cake-shaped sable hats known as shtreimels on Shabbat and holidays. Made from the tails of sables and foxes, the hats can cost as much as $5,000.

Hasidic men, seen here during a Rosh Hashanah ceremony in Brooklyn, have a tradition of wearing fur-lined hats on Shabbat and holidays. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Councilman Chaim Deutsch of Brooklyn cited the Hasidic custom as a reason why he opposes the ban. The legislation contains a religious exemption that would allow the sale of fur to those using it as part of their faith.

“If we ban fur and then you have people that are still out there wearing it, considering the fact that hate crime in New York City is on the rise, people will be targeted on the streets, saying, ‘Why are you wearing this if there’s a fur ban?’” Deutsch, an Orthodox Jew, told The New York Times.

Alexander Rapaport, a Hasid who runs a Brooklyn-based network of kosher soup kitchens, echoed Deutsch’s fears.

“There are thousands and thousands of citizens who wear [the shtreimel] for culture and tradition, and it’s almost symbolic to their way of life,” he told JTA.

Rapaport questioned the efficacy of the bill, since it would only ban fur in New York, and wondered whether it would put “a bulls-eye on every shtreimel.”

Some see the religious exemption as problematic and untenable. Bezalel Stern, an attorney at Kelley, Drye & Warren, LLP, representing the International Fur Federation, says the exemption violates the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause because it would favor religion and have the government evaluate the validity of a person’s religious claim.

Stern fears that if the law were to pass, the religious exemption would not stand up in court.

“I think the [City Council] speaker knows that the religious exemption is unconstitutional and he’s putting it in because he wants to — excuse my pun — pull the fur over people’s eyes in order to get it passed,” Stern said.

Marc Kaufman sells fur to a number of high-profile celebrities at his Manhattan store but says most customers are regular people. (Josefin Dolsten)

But the ban has Jewish proponents, too.

Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz, the founder of Shamayim: Jewish Animal Advocacy, criticized Hasidic opposition to the ban in an email to JTA, saying that wearing shtreimels is a custom but not mandated by Jewish law.

“It is not required to actualize holiness,” said Yanklowitz, who is Orthodox. “What is required, however, is the need to follow the notion of ‘tzar ba’alei chaim’: not causing needless pain to animals.”

Jewish Veg, which advocates for veganism in the Jewish community, also threw its support behind the bill. In a statement, the group said that fur industry practices constitute “egregious violations of Jewish ethics.”

“Judaism mandates that we treat animals with exquisite and sensitive compassion, and the practices of the fur industry grotesquely violate this mandate,” the organization said.

Meanwhile, Kaufman says he’s more focused on running his business than worrying about the legislation, which he believes is unlikely to pass.

“God will take care of everything,” he said. “Furs come from God, it’s part of the Bible.”