Need tefillin? There’s an app for that.

Published July 13, 2018

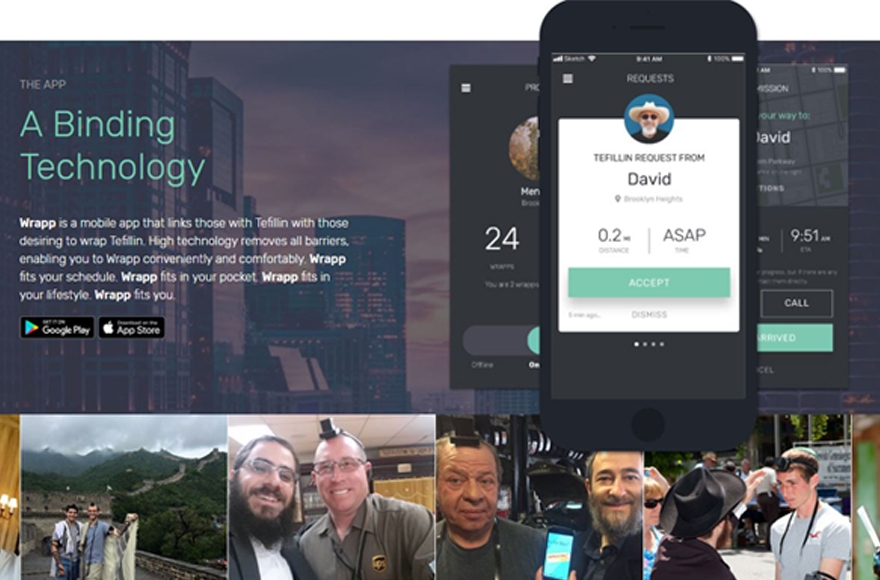

The brainchild of a 39-year-old Brooklyn businessman, Wrapp enables users to get tefillin for prayers for free. (Tefillinwrapp.com)

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — You can call a taxi, order a hamburger, rent a film and buy a book with a few clicks of a smartphone.

So why shouldn’t it be as easy to score a set of tefillin?

That, at least, was the question that led to the launch last month of Wrapp — an app its creator calls “the Uber of the tefillin world.”

It connects those who have tefillin — leather straps attached to a set of two small boxes containing scripture on parchment — with Jews who need them for morning prayers or other rituals. And it’s free.

The brainchild of a 39-year-old Brooklyn businessman, Wrapp hit app stores last month. It already has signed up more than 4,500 providers in the United States, Israel, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. Providers offer their tefillin to those making the request within a radius of 20 miles.

The app’s creator, a follower of the Chabad Hasidic movement named Shimon — he said he did not want to reveal his last name to avoid a “downpour of emails and suggestions,” – decided on a trip to Israel two years ago that this is what the world needs, he told JTA on Thursday. He met an old friend from the States who had made arrangements to borrow another person’s tefillin in Israel.

“It didn’t make sense to me that in a Jewish country, borrowing a tefillin should be such an issue. That’s when the idea came to me. I knew I was on to something big.”

Chabad is famous for soliciting Jews all over the world to partake in the tefillin ceremony. Worshippers use the straps to bind the small boxes to their forehead and bicep — a literal interpretation of the biblical injunction to bind God’s word “as a sign upon the hands and between the eyes.”

Among Chabad followers and others, getting Jews to perform the mitzvah, or positive commandment, even once will hasten the coming of the Messiah.

Although the app is also intended for observant Jews who forgot or lost their tefillin, Shimon said the typical user would be someone who had an impulse or inspiration to don a set.

Users tend to be people “who want to connect to God. And when people do, it is a very personal thing. Someone might reach out when they’re depressed, another when they’ve just signed a huge successful deal. Others on their mother’s yahrzeit,” he added, using the Yiddish word for the anniversary of a person’s death. “It’s different for every person.”

Those in need of a set can indicate their window of availability — a half hour, an hour or two hours. Providers within a range are pinged with the request. The first provider who accepts can then schedule a session at the requester’s location or propose a different location.

The project was a bit too big to take off immediately, Shimon said. Several app developers turned him down, citing the obstacles and costs of constantly updating software with thousands of simultaneous users.

Eventually he teamed up with Spotlight Design, a branding and marketing agency owned by Chabad followers in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, the world headquarters for the Chabad movement.

“They got it, they got super enthusiastic about it and they worked on it,” Shimon said.

Shimon wouldn’t say how he was supporting the project or how much it cost.

“First of all, it’s not a one-time investment – it constantly evolves and changes, so I don’t have a figure for you,” he said. “Maybe I could tell you when Messiah comes.”

Only a few dozen requesters have used the app, Shimon said. But it has not been officially launched or marketed.

An app that lets users summon an observant Jew to a predetermined address raises some security concerns at a time when Jews are frequently singled out for violence in Europe and beyond, Shimon acknowledged.

“Yes, it’s something that we’ve taken into account, which is why there’s a 20-mile limit” on how far a provider may be summoned to deliver tefillin, he said. “The assumption here is that you as a provider know your immediate surroundings. And of course our advice is: If it’s fishy, don’t go!”

The range can be changed to one mile.

Additionally, providers need to indicate on Wrapp that the action has been completed.

“When there’s an action that stays open for more than an hour or two, it raises flags and we can check to see what happened,” Shimon said. Wrapp is only usable during daytime, when tefillin is usually worn.

Orthodox Judaism considers wearing tefillin a commandment that only applies to men, although some Orthodox feminists and many more women in the Conservative and other non-Orthodox movements have taken up the ritual. Two weeks ago, Wrapp received its first request from a female. Shimon said that responding is up to the discretion of the individual providers, and Wrapp currently has no policy on the issue.

The new user turned out to be the non-Jewish caretaker of an elderly Jewish man who wanted to perform the ritual but had neither tefillin nor a smartphone.

Hillel Pikarskei, a Chabad rabbi in Paris, welcomes the “competition.” On his regular beat in Paris, which includes the leading falafel stores of the Marais, the city’s historic Jewish quarter, he said he has gotten about 13,000 Jews to put on tefillin.

“It sounds like a good thing, I like it,” Pikarskei said of the app. “You think it’s going to put me out of business? No way, my friend. I’m working in a world-renowned tourist spot. Don’t you worry about me.”