Jake Tapper’s professor brother Aaron writes an introduction to the range of ‘Judaisms’

Published March 10, 2017

(JTA) — Aaron Hahn Tapper was spending the summer of 1994 studying at an Orthodox Yeshiva in Jerusalem when he was called into the office of the school’s mara d’atra, or chief legal authority.

Noting that Tapper’s mother converted to Judaism under the auspices of the Conservative movement, the rabbi was blunt. “Well, it seems you may not be Jewish,” he said, explaining that Conservative conversions may or may not be acceptable to Orthodox authorities.

Tapper was allowed to continue his studies so long as he agreed to research the terms of his mother’s conversion: When was it done? Who witnessed her conversion ceremony? Were they men?

ADVERTISEMENT

Tapper had spent 13 years at Philadelphia Jewish day schools and 10 summers at Camp Ramah in the Poconos. The yeshiva’s challenge forced him to ask uncomfortable questions about Jewish law, beliefs and practice. Most of all, it raised questions about identity.

Long after the yeshiva eventually accepted his mother’s conversions, those questions stuck with Tapper, 43, through a career in Jewish and religious studies.

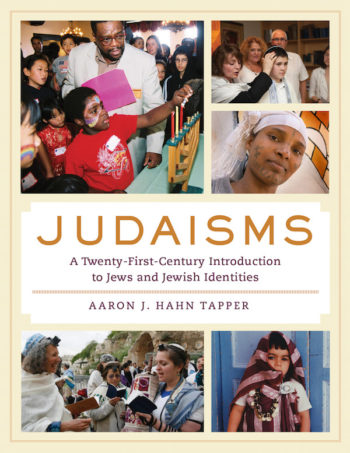

Now the Mae and Benjamin Swig Associate Professor in Jewish Studies at the University of San Francisco, Tapper has written an introduction to Judaism for the college student and general reader that puts identity questions front and center, starting with its title: “Judaisms: A 21st Century Introduction to Jews and Jewish Identities.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“Can someone’s identities be deleted overnight on a technicality?” he writes, after describing the yeshiva incident. “Does Jewishness really depend solely on ritual and legal requirements? Or are Jewish identities more malleable than that?”

At its core, the book is an attempt to answer the question, What does it mean to be a Jew?

“For someone who’s a ‘halakhic man’ — the way in which they understand the world is only through the lens of halachah [Jewish law] and that’s their construct — it’s a legal category,” Tapper told JTA in a recent interview. “You either are or are not — it’s black and white.”

Others believe in a Jewish soul, or “neshama,” that amounts to a metaphysical essence, or even genetic definition, apart from ritual and belief. Israel has its own definition, one that combines nationhood, citizenship and, increasingly, rabbinic oversight.

Then there is a postmodern approach, in which people become a part of a community simply by believing themselves to be part of a community.

In one way or another, all Jews are choosing to be Jewish — or at least have the luxury to do so in the 21st century — in a process Tapper and sociologists call “social identity performance,” which depends on the behaviors and choices they present to each other and the outside world.

“Most of us can’t trace ourselves back that many generations,” said Tapper. “There’s a certain acceptance that whatever we’re told by our parents are the facts. Ancestry doesn’t go back that far for most most of us.”

“Judaisms: A Twenty-First Century Introduction to Jews and Jewish Identities” (University of California Press)

In telling the story of Jews across the centuries and the continents, “Judaisms” — a finalist for a 2016 National Jewish Book Award — presents Jewish history less as a timeline than a tapestry. Tapper writes about Jewish communities that developed within Christian, Muslim and Hindu cultures; European Jews and Asian Jews; gay Jews and Jews of color; assimilated American interfaith famlies and Ethiopian Jews who consider marrying out of their sub-community a form of intermarriage.

He writes that “as far back as the Hebrew community, and through their subsequent rebirth as Israelites, Judeans and, eventually, Jews, this group has never been uniform or consistent. There has never been a Jewish people, only peoples. Within the Jewish tent there have always been subtribes, subidentities, and subfactions. And yet, even though the Jewish community has never been homogeneous or monolithic, Jews and non-Jews frequently speak about ‘the Jews,’ as if they are a single, cohesive, interconnected group.”

Tapper says his multicultural view of Jewish identity is shaped by his own experiences. Growing up in Philly (his older brother is Jake Tapper, the CNN anchor and chief Washington correspondent), he attended a Conservative-affiliated Solomon Schechter school (now the Perelman Jewish Day School) through grade eight, and high school at the unaffiliated Akiba Hebrew Academy, now the Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy in Bryn Mawr.

He was active with the Jewish community as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University, but was heavily influenced by the baal teshuvah community he found in Jerusalem, where rabbis took an almost evangelical zeal in introducing young American Jewish backpackers to the Orthodox lifestyle.

Tapper was both a participant in the baal teshuvah culture and an observer, fascinated about the ways these newly observant Jews “framed” their identities. Having grown up in a havurah, or informal congregation, that included some heavy-hitters from the Conservative movement — including Jeffrey Tigay, the onetime chair of the Jewish studies department at the University of Pennsylvania, and Chaim Potok, the rabbi and novelist — Tapper was able to think critically about the rigid Orthodoxy he saw at the baal teshuvah yeshivas.

“The guys around me [growing up] were no slouches, and I knew that they had a much more sophisticated understanding of things than I was being taught in this yeshiva,” he said.

Later he spent a summer in Fez, Morocco, on his way to getting a master’s degree in theological studies from Harvard and a doctorate in comparative religion at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “That started opening up my eyes to the Ashkenazi-centric perspective of what it means to be a Jew,” he recalled.

All those experiences led him to think less about Jewish boundaries and more about Jewish possibilities. “I’ve come to accept to some degree, what does it matter what I think if the person across from me thinks that they’re a Jew?” he said. “Their identity is critical to them and has everything to do with their meaning as a person. Ultimately I am not making institutional decisions, so I can be open-minded about that stuff.”

Tapper knows that such open-mindedness can be frustrating and even threatening to those who prefer strict criteria for belonging. “Just putting an ‘S’ at the end of Judaism can be very disruptive for people because they do have some sort of concrete notion of what a Jew is,” he said. “In reality, it is much, much, much more messy and complicated than that.”

Theory will one day meet practice, he realizes, especially as a father raising two Jewish children. He and his wife, Rabbi Laurie Hahn Tapper, the director of Jewish studies and school rabbi at the Yavneh Day School in Los Gatos, Calif., have two children, 6 and 9.

“When my kids want to pair off — that’s when I would have to answer, would I accept so and so as really Jewish?” said Tapper.