Israeli scientists identify new culprit behind cancerous growths: tumor-specific bacteria

Published July 27, 2020

REHOVOT, Israel — Despite their reputation, most bacteria are harmless. Many are vital to human life.

Others, however, cause infections that lead to fatal diseases ranging from tuberculosis to bubonic plague.

Add cancer to that list, at least indirectly. According to new research led by Dr. Ravid Straussman of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, bacteria living inside cancer cells are likely to have a profound effect on how different types of tumors behave.

“Most bacteria you find in tumors are known to be present in normal people, but there’s also a minority of bacteria that were never described in humans or any other host before,” Straussman said. “Some of these bacteria don’t even have names.”

While bacteria were first detected in human tumors more than 100 years ago, Straussman reported in a paper in the May 29 issue of Science that he found bacteria live inside the cells of many cancer types, and that each type of cancer houses unique populations of bacteria.

Breast cancer, which has a relatively high incidence among Jewish women, has a particularly rich and diverse microbiome.

“Overall, this research will change the diagnosis, management and prognosis of human cancer starting now and for many years to come,” said Daniel Douek, a senior investigator in the human immunology division of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Straussman began his research into bacteria nearly 10 years ago after wondering why cancer cells in patients don’t consistently respond to drugs the way they do in the lab.

“People think of tumors as a mass of cells that grows uncontrollably,” Straussman said in a recent interview at his 15-person laboratory at Weizmann’s Department of Molecular Cell Biology. “The truth is that tumors are just like any other organ.”

In Straussman’s most recent project, he and his team took tumor samples from 1,526 patients with seven cancer types — breast, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, melanoma, bone and brain — and found different assortments of bacteria that correlated with specific tumor types. Interestingly, he discovered that about 70% of breast cancer patients have bacteria in their tumors.

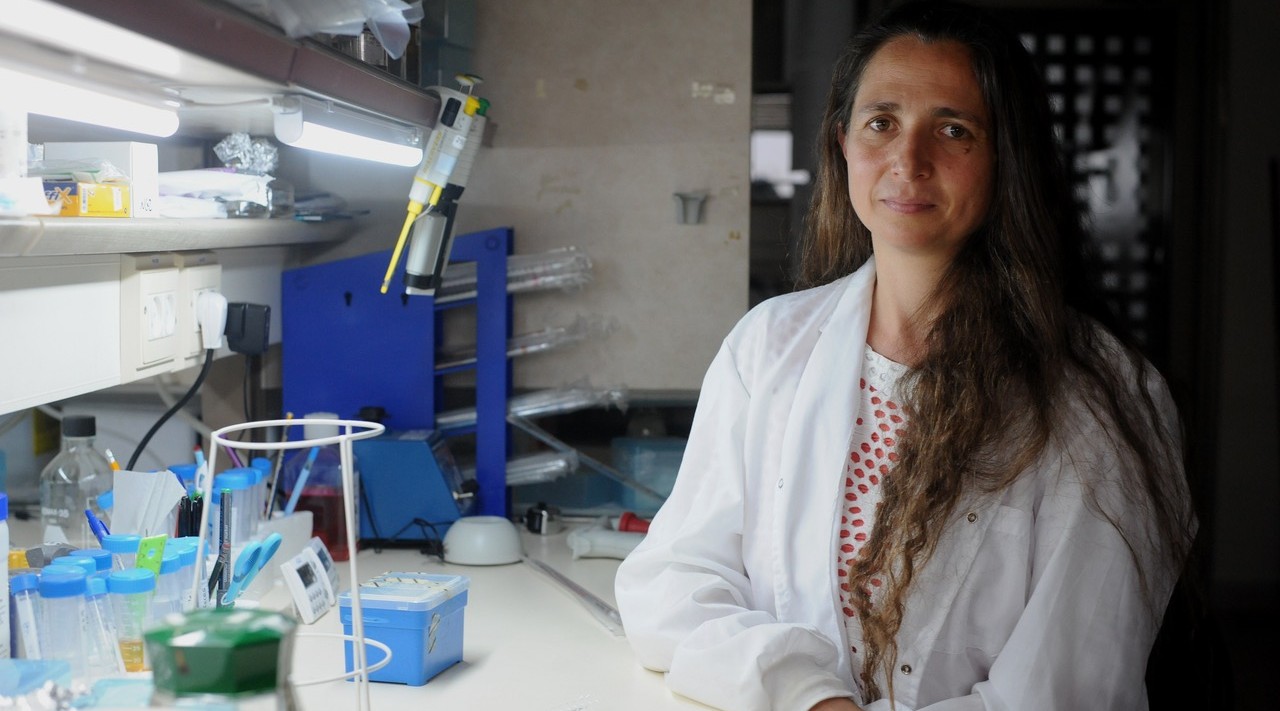

Dr. Naama Geva-Zatorsky of the Technion Integrated Cancer Center in Haifa is among a growing number of cancer researchers studying bacteria that live in the gut microbiome. (Courtesy of the Technion)

“Some of these bacteria could be enhancing the anti-cancer immune response, while others could be suppressing it,” said Dr. Mark Israel, executive director of the Israel Cancer Research Fund, or ICRF. “This is important because specificity in biology means that those bacteria are playing some biologic role. In other words, if there wasn’t a reason for those bacteria to persist, the body would reject them.”

Since 2016, ICRF has been funding Straussman’s work with grant funding exceeding $300,000. The organization, which raises millions of dollars in North America for cancer research, supports scientific investigations at more than 20 institutions across Israel.

“The unique finding of Straussman’s paper is that the collections of bacteria within tumor cells vary from tumor type to tumor type,” Israel said. “They must be providing some sort of advantage to the tumor cells, or doing something that contributes to the tumor’s behavior. Therefore, there’s a lot of interest in getting rid of them, and hopefully having a therapeutic effect.”

Straussman said his latest study may also shed light on why some bacteria are drawn to certain cancer cells and why each cancer has its own typical microbiome.

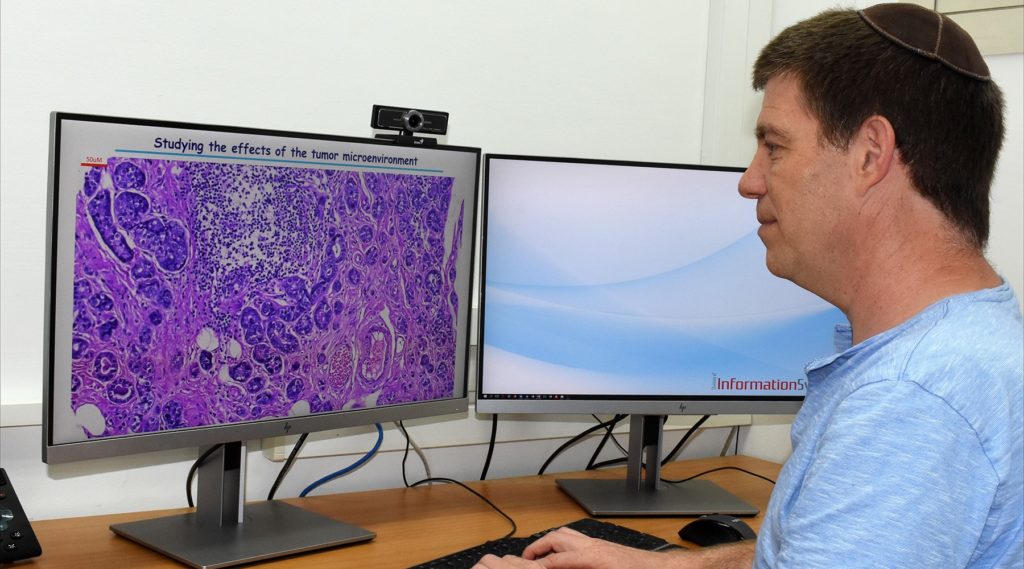

Tumors are complex ecosystems that are known to contain immune cells, stromal cells, blood vessels, nerves and many more components in addition to cancer cells. They’re all part of what’s known as the tumor microenvironment.

“Our studies, as well as studies by other labs, clearly demonstrate that bacteria are also an integral part of the tumor microenvironment,” Straussman said. “We hope that by finding out how exactly they fit into the general tumor ecology, we can figure out novel ways of treating cancer.”

Straussman inspects images of bacteria in a tumor in his lab at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot. (Larry Luxner)

Dr. Naama Geva-Zatorsky of the Technion Integrated Cancer Center in Haifa is doing related research. She’s one of a growing number of cancer researchers worldwide who study bacteria that live in the gut microbiome.

Supervising a 10-person lab, she has tested at least 60 types of bacteria that thrive in the human gastrointestinal tract. Geva-Zatorsky hopes to learn whether the immune effects of gut bacteria can be used either to prevent cancer from forming or to increase the efficacy of cancer treatments.

“We believe we can induce an environment where cancer cannot develop,” she said. “Maybe in the future bacteria that stimulate the immune system can be added to immune therapy, so that the cancer can be eradicated more quickly and efficiently.”

Her work, too, is being funded by the Israel Cancer Research Fund.

“We’ve known for centuries that the bacteria in your gut play important roles, but in the last three to five years it’s been discovered that a collection of bacteria influences your immune response,” Israel said. “That’s important now because of the major new modalities of treatment that modify the immune system to fight off the tumor.”

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Israel Cancer Research Fund, whose ongoing support of these and other Israeli scientists’ work goes a long way toward ensuring that their efforts will have important and lasting impact in the global fight against cancer. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.