Israeli researchers use novel methods to seek treatments for deadly pancreatic cancer

Published January 11, 2021

By the time Barbara Goodman was diagnosed with Stage IV pancreatic cancer in October 2001, there were already 30 tumors in her liver.

“We knew we were in for a pretty tough battle,” recalled her husband, Kenneth Goodman, then president of New York-based Forest Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company. “But I had an entire research organization I could draw upon.”

Nevertheless, nine months after her diagnosis, Barbara died. She was only 51, far younger than usual for pancreatic cancer patients, who are diagnosed, on average, at 70.

ADVERTISEMENT

In his wife’s memory, Kenneth established the Barbara S. Goodman Endowed Research Career Development Award for Pancreatic Cancer at the Israel Cancer Research Fund, which supports scientific research in Israel with funds raised in North America.

“As an executive in the pharma world, you get a pretty good understanding of research. But for pancreatic cancer, there are virtually no cures or treatments,” Goodman said in a recent webinar organized by ICRF. “I knew we needed to do a lot of very basic research. I felt this was something done best in Israel, by Israeli scientists who have had great success with other cancers.”

Tumor markers for early diagnosis

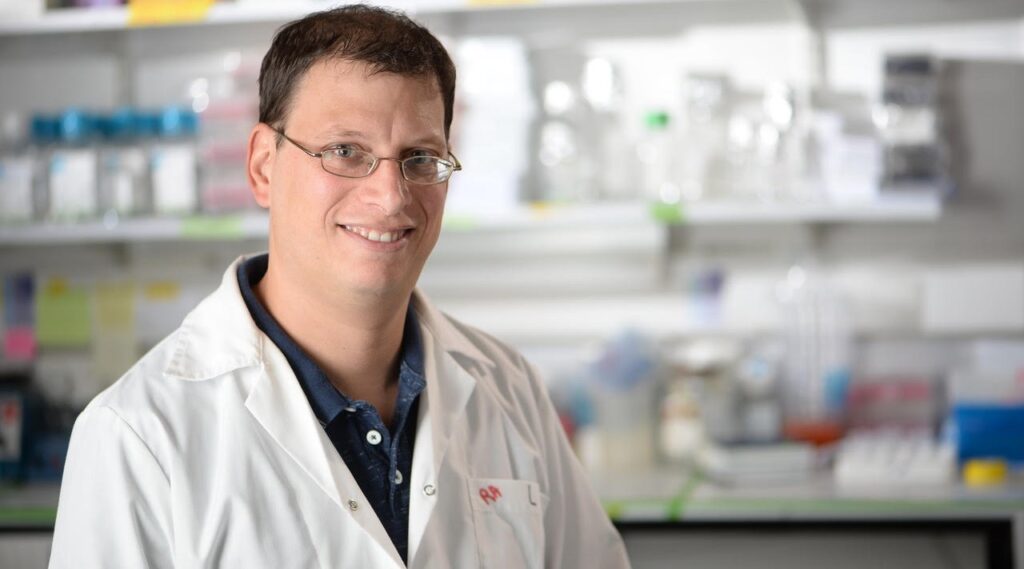

This year’s recipient of the award created in Barbara’s memory is Dr. Oren Parnas of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University. His $135,000 ICRF grant will fund a three-year effort to profile individual pancreatic cancer cells from early stage tumors.

ADVERTISEMENT

Using a model in which he activates a cancer-causing gene to introduce cancer into mice, Parnas and his team will profile the genes of individual pancreas cells from pre-malignant lesions two weeks after initiation of the cancer-causing genes, six weeks afterward and at other intervals up to 15 months. He’ll then compare those findings to human tissues in order to discover markers for early diagnosis.

Pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to diagnose early due to the absence of symptoms. The pancreas is located deep in the abdominal cavity where a cancerous tumor can expand undetected. Late-stage symptoms reflect a loss of normal pancreatic function and include weight loss, yellowing of eyes and skin, severe abdomen or back pain, and gallbladder and liver enlargement.

“Although pancreatic cancer is generally diagnosed after the cancer has already spread, it develops over a long time, in many cases for more than 10 years, without any symptoms,” said Parnas, who studied industrial engineering and worked at Bank Hapoalim as an economist before realizing that science was his true calling. “You can’t screen the whole population” for the disease, he said, “but on the cellular level you can see changes during this time.”

Dr. Oren Parnas of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University is profiling individual pancreatic cancer cells from early stage tumors in a bid to discover markers for early diagnosis. (Aviad Weissman)

Improving detection and treatment is critically important. While pancreatic cancer ranks 11th in prevalence among all cancers in the United States, it’s the third-deadliest, after lung and colorectal cancers. The survival rate for pancreatic cancer is only 20% after one year and 7% after five years, according to the American Cancer Society. People with Stage IV pancreatic cancer live on average two to six months after diagnosis.

In recent months, “Jeopardy” TV host Alex Trebek, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Civil Rights leader and congressman John Lewis all died of pancreatic cancer. This year, some 57,600 Americans will have been diagnosed with the disease, and about 47,000 Americans will die from it.

Resistance to radiation

Leading risk factors for pancreatic cancer include smoking, obesity and alcohol consumption, and an individual’s chances of developing the disease increase with age. Another risk factor is mutations of the BRCA gene, which Ashkenazi Jews have in higher prevalence than the general population and which leads to higher rates of breast and ovarian cancer.

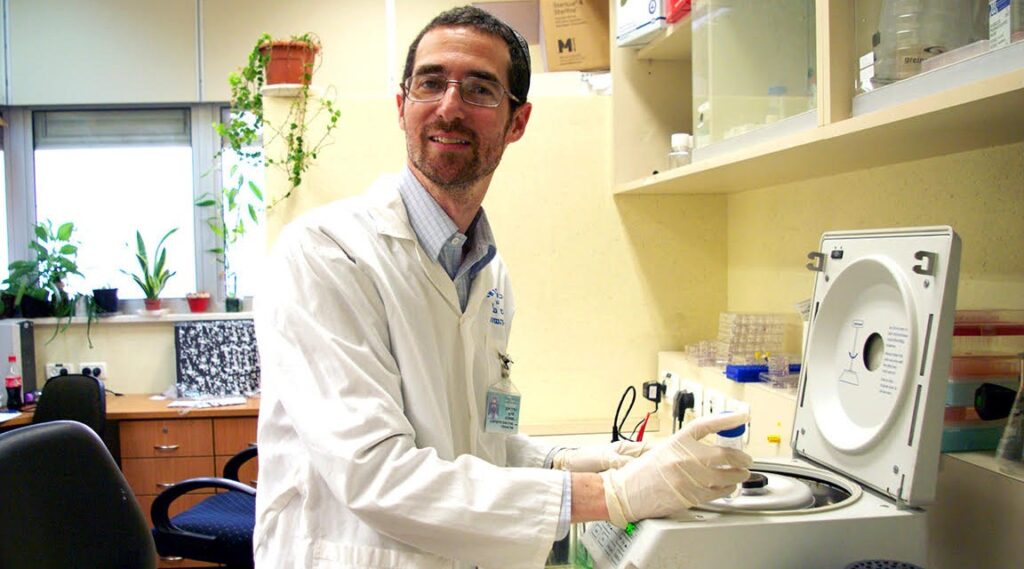

“There is some association with BRCA, but pancreatic cancer rates are only a little higher among Jews or Israelis than anyone else,” said Dr. Yaacov Lawrence, a radiation oncologist at Sheba Medical Center near Tel Aviv. “The incidence of pancreatic cancer is increasing, and treatment options even today are very limited. The pancreas is very hard to cut out because it’s in a difficult place for surgeons to get at, and cancers have often metastasized by the time they’re discovered.”

Pancreatic cancer is particularly resistant to chemotherapy and radiation. The tumors rarely shrink, even after exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation. Lawrence thinks tumor cells are able to resist radiation by rewiring their metabolism.

“Each cell is like a little person,” explained the oncologist, who immigrated to Israel 23 years ago from Britain. “They each need their sources of energy, and we’ve known for many years that cancer cells have slightly different ways of processing food than normal cells. We hypothesized that maybe this difference in how cancer cells process their food underlies their resistance to radiation.”

Lawrence, funded by a three-year ICRF grant, is studying how the tumor’s resistance to radiation may be affected by its abnormally high appetite for glucose, the most common form of sugar, and other nutrients. He is conducting this research in collaboration with Dr. Eyal Gottlieb, an expert in cancer metabolism at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, and Dr. Ariel Shimoni Sebag, a cancer biologist at Hebrew University.

Dr. Yaacov Lawrence, a radiation oncologist at Sheba Medical Center near Tel Aviv, is studying how pancreatic cancer tumors’ resistance to radiation may be affected by their abnormally high appetite for glucose, the most common form of sugar, and other nutrients. (Courtesy of Yaacov Lawrence)

Improving chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer

Dr. Ziv Gil, head of the Technion’s Applied Cancer Research Laboratory, has received an ICRF grant for research on the cellular mechanisms underlying the spread, or metastasis, of pancreatic cancer cells. Gil is studying how pancreatic cancer cells can migrate along axons, or nerve fibers — a mechanism known as neural tracking.

“One of the hallmarks of pancreatic cancer is its ability to invade and progress through nerves,” Gil said. He and his team already have discovered the mechanism by which cells called macrophages help spread cancer from the pancreas to other organs.

“It’s as if the body senses the cancer as an inflammation, and it sends these cells to fight the cancer. But instead of fighting the cancer, these small cells nourish it,” said Gil, who is also a senior physician in the Technion’s Department of Otolaryngology, and director of head and neck surgery at Rambam hospital in Haifa. “Now we are trying to imitate the transmission of these signals between the macrophages and cancer cells in order to package chemotherapy within these signals that can target the cancer.”

At present, Gil’s team, supported by ICRF funding, is doing preclinical trials on mice to develop synthetic biological materials that deliver chemotherapy to cancer cells. Human clinical trials, he said, are still a few years away.

Rambam colleague Dr. Erez Hasnis, also an ICRF grantee, is taking a close look at one particular protein, RNF125, whose levels seem to drop as pancreatic cells become malignant. This, he said, happens in normal cells as digestive enzymes are synthesized and secreted. They get injured and replaced, and at some point, mutations start to accumulate. Scientists do not yet know why some people develop full-blown pancreatic cancer and others don’t.

Yet often, Hasnis said, the pancreas simply cannot keep up with our food intake.

“As we eat more and more, our pancreas gets exhausted. Eventually some cells start to die and other cells need to replace them, in a process that makes the pancreas cells prone to malignant transformation,” Hasnis said, citing several published papers linking pancreatic cancer to obesity and high caloric intake.

Hasnis also wants to know why this particular cancer is so aggressive when it comes to metastatic spread. To find out, he has developed a method in which pancreatic cancer is resected in a mouse model, allowing his team to observe how liver metastasis develops. This allows him to isolate specific genes involved in cancer seeding.

“Hopefully in a few years,” he said, “we’ll be able to use novel molecules to target the metastatic process.”