In the #MeToo era, these synagogues are banning Shlomo Carlebach songs

Published January 30, 2018

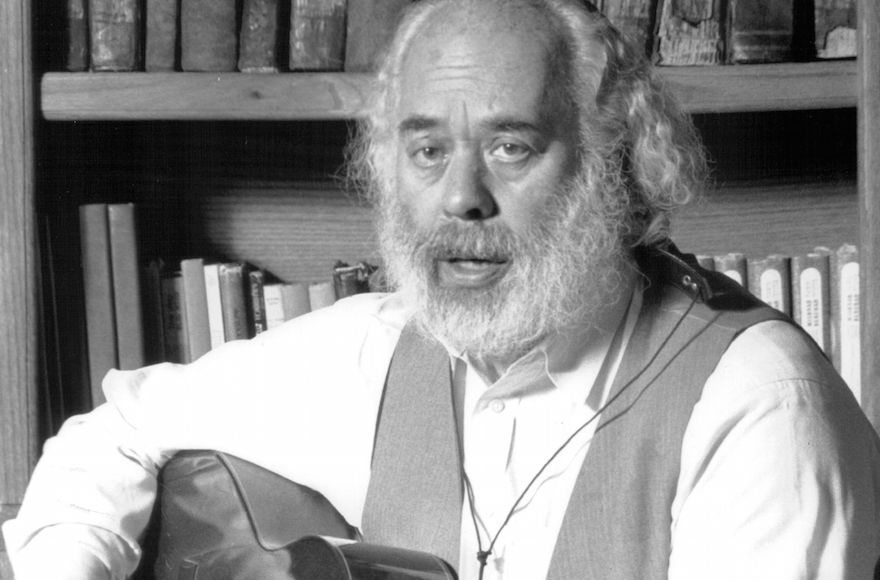

Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, seen in a 1989 photo, was perhaps the most prominent 20th-century composer of American Jewish music. (Dave Buresh/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

NEW YORK (JTA) — When Rabbi Angela Buchdahl announced how her synagogue would respond to the #MeToo moment, she singled out a man. But he wasn’t one of her congregants, synagogue clergy or staff members.

He was Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, perhaps the most prominent 20th-century composer of American Jewish music. Carlebach penned a vast body of songs and liturgical melodies heard in worship services, summer camps and sing-alongs. His music is sung in synagogues from nearly every denomination.

But in the years after his death in 1994, numerous women came forward to allege that he sexually assaulted them.

In her Jan. 19 sermon to New York’s Central Synagogue, one of the largest congregations in the country, Buchdahl announced that the synagogue would not sing his melodies for a year. The moratorium is taking effect across the synagogue — in services, in Hebrew school, in nursery school.

“We hope this communicates to those who have been victimized by Carlebach that we hear you and we are not indifferent,” Buchdahl said in the sermon. “In this coming year, we will see what new music emerges in the vacuum that is created with Carlebach gone.”

Central Synagogue is one of several in the United States, across denominations, that has stopped using Carlebach’s name, his teachings or his melodies in a debate that precedes but has been intensified by the #MeToo moment. The decisions are mostly a response to the sexual assault allegations that first appeared in a 1998 article in Lilith, the Jewish feminist magazine, and since have continued to surface.

Because they were aired publicly after his death, he never responded publicly to the claims, which range from dry humping and groping to unwanted kissing. Some of the women were underage at the time of the incidents.

“Essentially it felt like it was time to listen and take a reckoning to people we ignored who came forward with their tales of sexual assault,” Buchdahl told JTA. “We should not be in the business of banning any kind of art. I knew that was not the right option for us, but continuing to do nothing was also not an option.”

To excise Carlebach is no easy endeavor. His melodies, recorded from 1959 until his death in 1994, are often the most recognizable tunes to common Jewish prayers — particularly the Friday night service welcoming Shabbat. Synagogues will host “Carlebach services” comprised largely of his tunes.

For a time, Carlebach based himself out of San Francisco, and his music, which combines Hasidic and folk influences, was a Jewish touchstone of the 1960s counterculture. His song “Am Yisrael Chai” (“The Nation of Israel Lives”) served as an anthem for the movement to free Soviet Jewry. He also developed a personal mythology and dedicated following, and at concerts would intersperse his songs with intimate stories.

Recognizing the pervasiveness of Carlebach’s music, some synagogues continue to sing his songs but don’t refer to him by name or share his stories. The Modern Orthodox Anshe Sholom B’nai Israel Congregation in Chicago still hosts a Carlebach service but has not used his name for years. The synagogue’s rabbi, David Wolkenfeld, said the misconduct allegations mean Carlebach should no longer be revered as a personal example.

“The allegations about him were sufficiently credible and sufficiently serious and sufficiently numerous that he did not deserve to be treated as a rabbi, as a religious authority figure,” Wolkenfeld said. “I also realized that if there were victims or their children or grandchildren in the congregation, what would it mean to them to hear someone who abused them being referred to as this great rabbi?”

It’s also technically difficult to ban Carlebach’s music, said Rabbi Barry Kornblau of the Orthodox Young Israel of Hollis Hills-Windsor Park in Queens, New York. Kornblau also has not used Carlebach’s name for years, but said people do not always know which tunes are Carlebach’s, and that it is difficult to manage every melody in Orthodox services, which are often led by lay members.

“I’m dealing with real human beings in a communal setting,” Kornblau said. “If I were to use language like ‘prohibition,’ I would have to take some prayer leader who goes into a song and, A, know it was from Carlebach, and B, stop him in public. I’m not going to do that.”

These rabbis are, in a way, confronting the same question that has occupied the creative world since the wave of misconduct allegations against industry figures began last year: Is it possible to separate the art from the artist? Some say yes. Other activists, however, believe that because Carlebach was a spiritual leader who wrote melodies for prayers — and worshippers use those melodies in the act of prayer — his work carries more moral weight than a movie.

“I think there’s a huge difference between Woody Allen and someone who used spirituality and religion and God’s name to gain access,” said Sharon Weiss-Greenberg, executive director of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, who advocates a hard ban on using Carlebach’s music. “There’s a difference between one’s choice to attend a movie screening and one’s showing up to services at shul and having the choice taken away from them.”

Other clergy see a Carlebach music ban as an opportunity to expand their repertoires. A Facebook group called Anything But Carlebach, with more than 1,200 members, has banned discussion of his behavior and serves as a clearinghouse for new or obscure melodies to prayers. Large segments of American Jewry — including many Sephardic and Hasidic communities — have their own musical traditions that predate Carlebach.

“Jewish music has a rich, varied and long tradition well before Shlomo Carlebach’s music,” said Cantor Jessica Leash, who runs Silicon Valley Jewish Meetup, an independent community in Northern California. “If we keep working in this material, not acknowledging its origin and not making any room for new material to come forward, we’re basically shutting a door.”

Despite the allegations, some of Carlebach’s followers still see immense value in his teachings and music. His daughter Neshama, a singer who has carried on his legacy, wrote an essay in The Times of Israel in January in which she said she supports “the countless women who have suffered the evils of sexual harassment and assault” and acknowledged her father had hurt some women. But she defended her father as a kind and caring spiritual leader who advanced women’s rights.

“I do not recognize the version of my father that some people describe,” she wrote. “To me, he was the kindest, most respectful, most loving person to my friends and me. I myself witnessed him as a deeply passionate supporter of the role of women as leaders.”

Another Carlebach follower, Aryae Coopersmith, believes the allegations and included them in his book on Carlebach’s movement. But he said it would be wrong to erase Carlebach’s music and stories, which for many have served as an inspiration.

“His songs for so many people have opened our hearts to what our tradition, what our grandparents, have been teaching us for so long,” said Coopersmith, who co-founded the House of Love and Prayer, Carlebach’s Jewish synagogue-cum-commune in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district known for birthing the 1960s counterculture movement. “They open our hearts to connecting with Hashem, with Torah, with other human beings. They’re so much a part of who we are today as Jews.”

Carlebach will endure as a major influence on Jewish music despite the allegations, said Joey Weisenberg, a Jewish composer whose Americana-inspired melodies are growing in popularity. Weisenberg said that “it’s not possible to ignore the melodies and the spirituality and the community empowerment and the beauty that Carlebach unleashed in the world,” but that Carlebach also betrayed his responsibility as an iconic Jewish musician.

“When we open our hearts in song, we have to take care of each other,” Weisenberg said. “The story we really tell is about the power of music and spiritual life in the world, and how we need to treat that power with extreme care. Shlomo Carlebach had an immense musical spiritual power, and clearly he misused and abused that power.”