In new HBO doc, a look at writer-AIDS activist Larry Kramer, warts and all

Published June 23, 2015

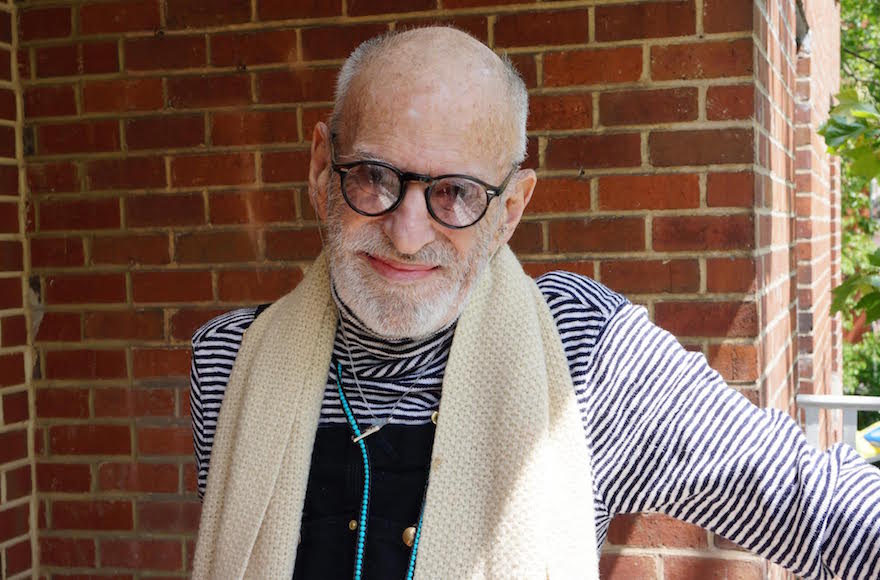

The life and work of Larry Kramer is examined in the HBO documentary “Larry Kramer In Love & Anger.” (Courtesy of HBO)

(JTA) — It wasn’t so long ago that gay men were vilified by American society at large. Back in the 1980s, when the AIDS epidemic surfaced, priests railed against them, claiming the disease was God’s revenge for sinful lifestyle choices.

That, of course, has changed — mostly. While there are still regular examples of anti-gay sentiments (and violence), HIV/AIDS is no longer the scourge it once was. Most Americans now support same-sex marriage and the practice is now legal in most states.

If there is one person responsible for this shift in mindset, it’s the outspoken activist, author and playwright Larry Kramer. He is the subject of a powerful and sad new HBO documentary.

“Larry Kramer In Love & Anger” is accurately described as a “warts and all” biography of a passionate man who because of his take-no-prisoners attitude managed to alienate almost everyone — gays and straights — on both sides of every issue on which he took a stand. But as the film makes clear, were it not for his courage and confrontational style, many more lives would have been lost to the AIDS crisis of the ’80s.

Kramer was born in Connecticut in an unhappy Jewish home. His father constantly berated him, calling him a “sissy” and urging him to behave more like his athletic older brother, Arthur. Though there is no excuse for it, dad’s attitude was typical of the times.

Kramer’s life became so untenable that while a student at Yale, he attempted suicide — also, sadly, not unusual at the time among young sexually confused men and women.

Early in his career, Kramer worked for Columbia Pictures. He was nominated for an Academy Award in 1969 for his screenplay of D. H. Lawrence’s “Women in Love” and made a ton of money for a terrible musical adaptation of “Lost Paradise.”

But Kramer felt movies weren’t the right platform in which to explore homosexual themes. After a brief and largely unsuccessful foray into theater, he wrote the novel “Faggots,” inspired by his experiences living on Fire Island, a summer haven for gays off the coast of Long Island, N.Y. The main character, Fred Lemish, loosely based on Kramer himself, was tired of the promiscuous gay lifestyle and was searching for love.

The book — and Kramer himself — was pilloried in the gay press, saying it portrayed a negative image of gays and their lifestyle. However, it has never been out of print and is among the best-selling gay novels in history. That may be because it was prescient.

In the early 1980s, Kramer’s friends became sick. Many died of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a heretofore rare form of cancer that seemed to hit gay men. Formerly disabused of political activism, Kramer banded together with some influential gay men and formed the Gay Men’s Health Crisis center. GMHC became the largest organization providing assistance to men with HIV/AIDS.

Activists from ACT UP, a group co-founded in 1987 by Larry Kramer, shown in an archival photo from a demonstration. (Courtesy of HBO)

But it wasn’t a good fit. Kramer was far more strident than his fellow GMHC board members, calling out politicians and bureaucrats — many of whom he knew were closeted — for not doing more to find a cure. His sometimes over-the-top militancy created a schism with other GMHC leaders. When he wasn’t invited to a meeting with Mayor Ed Koch — one of his frequent targets — Kramer threatened to quit. His resignation was accepted.

Frustrated, Kramer fled to Europe. On tour, he visited Dachau concentration camp. Like many Jewish men of his generation, he was impacted by the Holocaust and believed he was witnessing a Holocaust against gays.

Deeply moved, Kramer settled in London, where he wrote the first draft of what became “The Normal Heart” in six weeks. It’s a largely autobiographical play in which Kramer rages against both the straight establishment and gay leaders for their passivity.

The play, about subjects swept under the carpet at the time, was brilliant, moving and brave. It had a lengthy run off-Broadway, followed by numerous productions around the world, a recent Broadway revival and a 2014 HBO film that won an Emmy Award.

But progress in the real world remained slow. In 1987, Kramer was part of a group that formed ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power), which used civil disobedience as a tool to roust naysayers out of their slumber.

Even here, Kramer’s confrontational style stood out. The HBO documentary features interviews with ACT UP cohorts laughing about the way Kramer screamed at them when they were, say, debating what slogan to put on T-shirts to be worn at a protest. He’d yell, “Why are you worrying about f***ing T-shirts when we should be on the streets?”

Many of the scenes toward the end of the film were shot in 2013, and sadly depict a frail Kramer, hospitalized with complications from liver damage. (Kramer was diagnosed as HIV positive in 1988 and the recipient of a liver transplant.) At his hospital-bed wedding to longtime companion David Webster in 2013, he was too weak to say “I do.”

Filmmaker Jean Carlomusto has done a remarkable job seamlessly blending archival footage with current interviews to paint a portrait of this provocateur who would not let anyone or anything stand in his way. It’s a lesson to us all — and, as a result, this is not just a good film, it’s an important one.

(“Larry Kramer In Love & Anger” premieres on HBO at 9 p.m. Monday, four days after his 80th birthday.)

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.