How the Jews nearly wiped out Tay-Sachs

Published August 11, 2017

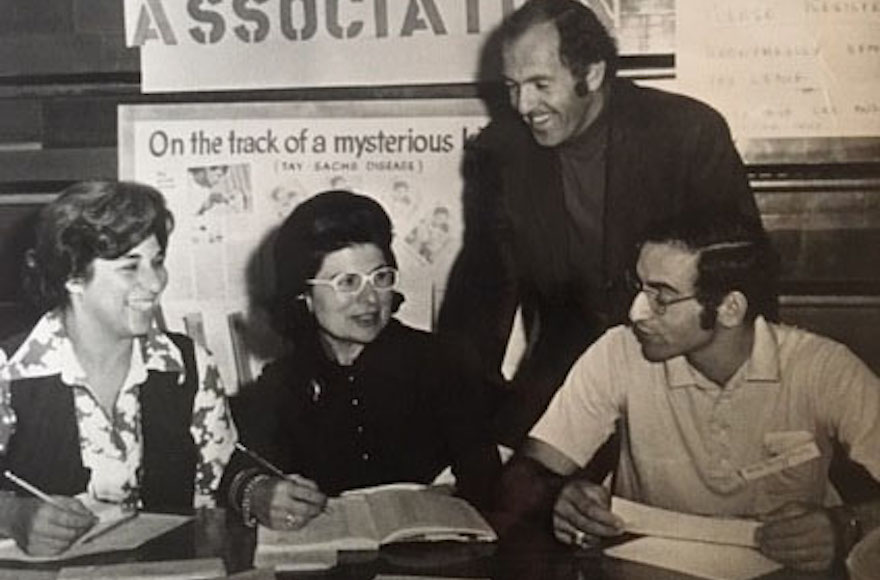

Widespread testing is credited with helping reduce the incidence of Tay-Sachs among Jews by more than 90 percent since screenings began in the early 1970s. (Courtesy of National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases Association)

This story is sponsored by JScreen.

Parents of children born with Tay-Sachs disease talk about “three deaths.”

There is the moment when parents first learn that their child has been diagnosed with the fatal disease. Then there is the moment when the child’s condition has deteriorated so badly — blind, paralyzed, non-responsive — that he or she has to be hospitalized. Then there’s the moment, usually by age 5, when the child finally dies.

There used to be an entire hospital unit — 16 or 17 beds at Kingsbook Jewish Medical Center in Brooklyn — devoted to taking care of these children. It was often full, with a waiting list that admitted new patients only when someone else’s child had died.

But by the late 1990s that unit was totally empty, and it eventually shut down. Its closure was a visible symbol of one of the most dramatic Jewish success stories of the past 50 years: the near-eradication of a deadly genetic disease.

Since the ‘70s, the incidence of Tay-Sachs has fallen by more than 90 percent among Jews, thanks to a combination of scientific advances and volunteer community activism that brought screening for the disease into synagogues, Jewish community centers and, eventually, routine medical care.

Until 1969, when doctors discovered the enzyme that made testing possible to determine whether parents were carriers of Tay-Sachs, 50 to 60 affected Jewish children were born each year in the United States and Canada. After mass screenings began in 1971, the numbers declined to two to five Jewish births a year, said Karen Zeiger, whose first child died of Tay-Sachs.

“It had decreased significantly,” said Zeiger, who until her retirement in 2000 was the State of California’s Tay-Sachs prevention coordinator. Between 1976 and 1989, there wasn’t a single Jewish Tay-Sachs birth in the entire state, she said.

The first mass screening was held on a rainy Sunday afternoon in May 1971 at Congregation Beth El in Bethesda, Maryland. The site was chosen in part for its proximity to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. One of the two doctors who discovered the missing hexosaminidase A enzyme, John O’Brien, was visiting a lab there, and another Johns Hopkins doctor, Michael Kaback, had recently treated two Jewish couples with Tay-Sachs children, including Zeiger’s. Zeiger’s husband, Bob, was also a doctor at Johns Hopkins.

The screenings used blood tests to check for the missing enzyme that identified a parent as a Tay-Sachs carrier.

“With the help of 40 trained lay volunteers and 15 physicians, more than 1,500 people volunteered for testing and were processed through the ‘system’ in about 5 hours,” Dr. Kaback later recalled in an article in the journal Genetics in Medicine. “For me, it was like having written a symphony and hearing it for the first time—and it went beautifully, without glitches.”

A machine to process the tests cost $15,000. “We had bazaars, cake sales, sold stockings, and that’s how we raised money for the machine,” Zeiger said.

In the days before Facebook or email, activists and organizers spread the word about mass Tay-Sachs screenings through newspaper and magazine articles, posters at synagogues, and items in Jewish organizational newsletters. (Courtesy of National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases Association)

Before screening, couples in which both parents were Tay-Sachs carriers “almost always stopped having children after they had one child with Tay-Sachs, for fear of having another,” Ruth Schwartz Cowan wrote in her book “Heredity and Hope: The Case for Genetic Screening.”

But with screening, Tay-Sachs could be detected before birth, and “carrier couples felt encouraged to have children,” she wrote.

Dr. Kaback’s work helped enable thousands of parents who were Tay-Sachs carriers to have other, healthy children.

“What he did for Tay-Sachs and how he helped so many families was amazing,” Zeiger said. “People named their kids after him.”

The screenings were transformative, and the campaign to get Jews tested for Tay-Sachs took off. This was the days before Facebook or email, so activists and organizers spread the word about screenings through newspaper and magazine articles, posters at synagogues, and items in Jewish organizational newsletters. Volunteers and medical professionals spoke on college campuses and sent promotional prescription pads to rabbis, obstetricians, and gynecologists. Doctors and activists enlisted rabbis and community leaders to encourage couples to be tested before getting married.

Another early mass screening event was held at a school in Waltham, Massachusetts, guided by Edwin Kolodny, a professor at New York University medical school. The first mass screening in the Philadelphia area was on Nov. 12, 1972, at the Germantown Jewish Center, and drew 800 people, according to a Yale senior thesis by David Gerber, “Genetics for the Community: The Organized Response To Tay-Sachs Disease, 1955-1995.”

Nearly half a century later, the Tay-Sachs screening effort remains a model for mobilizing a community against genetic disease. Parent activists, scientists and doctors are trying to emulate that model with other diseases and other populations.

“You can’t be complacent, because now there are 200 diseases you can test for,” said Kevin Romer, president of the Matthew Forbes Romer Foundation and a past president of the National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases Association. The foundation is named for Romer’s son Matthew, who died of Tay-Sachs in 1996.

Romer and others involved with this issue stress the importance of screening interfaith couples, too. Non-Jews may also benefit from pre-conception screening for Tay-Sachs and other diseases. Some research indicates, for example, that Louisiana Cajuns, French Canadians and individuals with Irish lineage may also have an elevated incidence of Tay-Sachs.

Scientific progress means that Jews can now be screened for over 200 diseases with an at-home, mail-in test offered by JScreen. The four-year-old nonprofit affiliated with Emory University’s Department of Human Genetics has screened thousands of people, and the subsidized fee for the test – about $150 — includes genetic counseling.

While some genetic tests are standard doctor’s office procedure for pregnant women or couples trying to get pregnant with a doctor’s help, JScreen aims for pre-conception screening. The test includes diseases common in those with Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Mizrahi backgrounds as well as general population diseases, making it relevant for Jewish couples and interfaith couples.

“Carrier screening gives people an opportunity to plan ahead for the health of their future families. We are taking lessons learned from earlier screening initiatives and bringing the benefits of screening to a new generation,” said Karen Arnovitz Grinzaid, executive director of JScreen. It was a path pioneered by the Tay-Sachs screening that began in 1971.

In Cowan’s book, she mentions a chart prepared by Dr. Kaback reporting on 30 years of screening: 1.3 million people screened, 48,000 carriers detected, 1,350 carrier couples detected, 3,146 pregnancies monitored.

“Kaback and his colleagues could well have stopped there,” she wrote. “But they did not. There is one more figure, the one that matters most and that goes the furthest in explaining why Ashkenazi Jews accept carrier screening… after monitoring with pre-natal diagnosis, 2,466 ‘unaffected offspring’ were born” to parents who were both Tay-Sachs carriers.

(This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with JScreen, whose goal of making genetic screening as simple, accessible, and affordable as possible has helped couples across the country have healthy babies. To access testing 24/7, request a kit at JScreen.org or gift a JScreen test as a wedding present. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.)