Growing up in Anne Frank’s shadow, my kids have known about the Holocaust since before they could speak

Published April 8, 2021

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — On a country road steeped in spring blossom, the 5-year-old in the backseat asked a question that sent shivers down our spines.

“Did the farmer plant those trees around his house because his family’s Jewish?” he asked us, his parents, pointing at a farmhouse we passed along the way.

I knew immediately what he meant.

“What do you mean?” I asked anyway.

“So people wouldn’t be able to see them from the road,” he replied.

It was startling evidence of how his mother and I — and perhaps life itself as a Dutch-Jewish boy — have allowed Holocaust traumas to mark his young mind and that of his younger sister.

For me, the revelation invoked a pang of guilt. But that feeling subsided into resignation of the reality of raising children in cities haunted by the ghosts of their murdered ancestors. For Europe’s Jews, that’s just our lot in life.

I told my son reassuringly that the farmer’s family probably wasn’t Jewish and that they wouldn’t need to hide even if they were.

But in my mind I was revisiting – one guilty flashback by another — all the times that I had exposed the kids to the Holocaust.

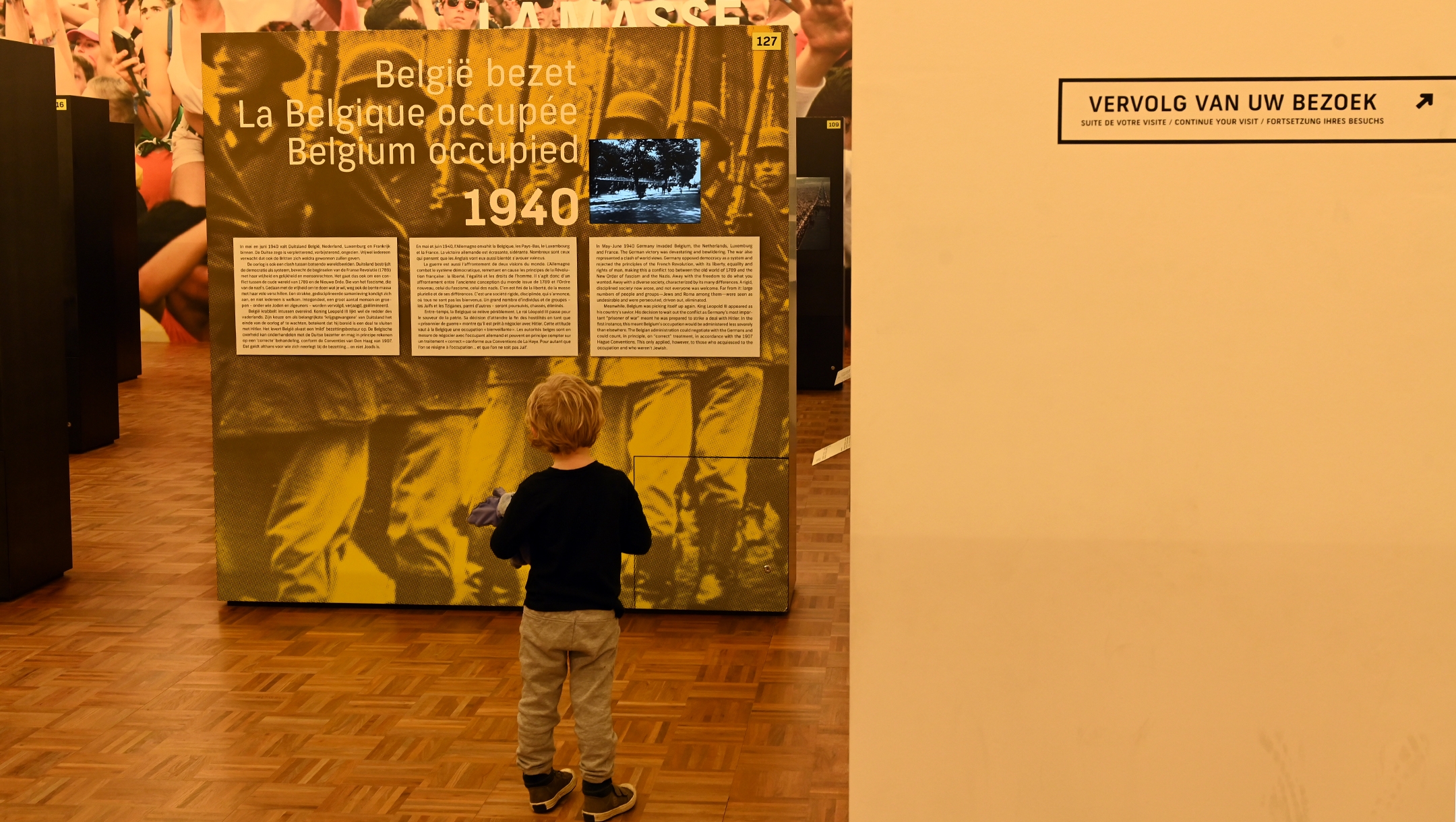

There was that rainy afternoon when I took them to the Holocaust museum in Mechelen, Belgium. We had some time to spare, I wanted to see the place and the two bottom floors were supposed to be age-appropriate. They deal only with the background to the genocide, which is explored in escalating order in the five-story building.

The author’s son visits the Kazerne Dossin Holocaust museum near Antwerp, Belgium, March 12, 2020. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

But the lobby had a temporary exhibition of drawings by an Auschwitz prisoner showing a Nazi flailing an inmate’s bare buttocks.

Questions followed. Answers flowed, including about how the Germans tried to kill Granny Hella at Auschwitz because she was Jewish. Before I knew it I mentioned gas chambers. Then I changed the subject and we walked in the rain to the nearest ice cream shop.

I’ve been obsessed with the Holocaust since a young age. I must have been 3 when Hella told me, sobbing intermittently, about how she had survived Auschwitz, the death marches and the carpet bombing of Dresden.

My job as JTA Europe correspondent isn’t helping me put distance from the genocide.

Clearly I’m partly responsible for introducing my very young children to horrific facts.

Some parents make the argument for starting early with age-appropriate Holocaust instruction. I’m not sure that’s such a bad thing, especially considering the mainstreaming of anti-Semitism today in Europe and the Netherlands.

In last month’s general elections here, the right-wing and COVID-sceptic Forum for Democracy party quadrupled its number of seats in parliament — it has eight now — despite a massive scandal over anti-Semitism in its ranks in November.

On the left, Green Left, the only party in the Dutch parliament that supports a boycott of Israel — and no other country — entered as a lawmaker Kauthar Bouchallikht, an activist who in 2014 posed for pictures in front of a sign reading “stop doing what Hitler did to you” at a pro-Palestinian demonstration. She has apologized for her actions.

But even if I’m overreacting, the H-word seems unavoidable for a Jewish-Dutch child who is being raised here to be invested in their identity.

For such Jews, the Holocaust seems everywhere in the Netherlands, where the Nazis and collaborators murdered at least 75% of the local Jewish population – the highest death rate in occupied Western Europe.

My father-in-law lives down the road from Anne Frank’s old apartment, before she went into hiding. On visits, the kids go with their saba, Hebrew for grandfather, to a playground just under that flat featuring a prominent statue of the teenage diarist that always has fresh wreaths at its feet, placed there by tourists.

Frost covers the Merwede Square in Amsterdam, where a statue of Anne Frank stands opposite her last home in which she and her family lived as free people. (Wikimedia Commons/Franklin Heijnen)

Their mother attended Frank’s former elementary school, which is now named for her. It sits about 500 yards from the playground.

The entrance to our children’s Jewish kindergarten has a life-size poster of Anne Frank. And there’s a building-size portrait of her towering over the passenger terminal of the ferry that we take several times a week to reach the city center.

On the streets of many Dutch cities, especially their native Amsterdam, shiny brass memorial cobblestones decorate the doorsteps of pretty much each building from which Jews were deported. They are magnets for inquisitive young children, especially my 4-year-old daughter, who tells me, “Look, Dad, Jews!” whenever she notices one (she seems to think they should make me happy).

Then there are the German-built massive bunkers that scar the entire length of the coastline; annual World War II memorial days with a two-minute silence where everybody stands still; and the innumerable references to the genocide in our heavily Jewish social circle and on television.

To help me think through it all, I called up a fellow Dutch-Jewish parent: Meir Villegas Henriquez, an Orthodox rabbi from Rotterdam. His two boys, aged 8 and 11, are a little older than my kids, so he has more experience with navigating the challenge of raising children in the shadow of the Shoah — and more insight into the potential trauma that might result.

Henriquez, 41, told me that he tries to filter the content that his children encounter about the Holocaust at a young age — but has come to terms with being unable to block it out.

His older son learned about the Holocaust in third grade at his non-Jewish school, Henriquez said. So the boy’s younger brother, who was then 5, also heard about it.

“And there are commemorations. It’s not something you can ignore for more than a few years as a parent,” he said.

Henriquez says he has some guidelines for his family. He tries to shield his sons from graphic images of the Holocaust and avoids taking them to museums with such pictures.

“Images have a tendency to burn into the mind,” he said.

Henriquez also works to show his sons that they are safe as Jews in the Netherlands through his volunteer work running Ohel Abraham, a nonprofit and study center that he founded for both Jews and non-Jews with an interest in Judaism.

“The boys see an openness to the outside world. They see many non-Jews with a warm sentiment toward Judaism, the Jewish people and Israel,” he said. “Such things create a balance. That’s the best you can strive for.”

Still, Henriquez has not shied away from turning the Holocaust into a sobering warning for his children.

“I try to instill vigilance, but not fears, phobias or paranoia,” he said.

He told his boys that the Holocaust “shows you need to be vigilant. Not trust the government. Any government. That Anne Frank and her family were betrayed by their countrymen.” (The exact circumstances of the Frank family’s capture remain a subject of debate among historians.)

Henriquez shares another lesson with his children.

“It shows why aliyah is a good idea,” he said, using the Hebrew-language word for immigrating to Israel as a Jew.

As an Israeli Jew living in the Netherlands, I see the appeal. And I confess that after some thought, I realize that a part of me doesn’t mind slightly traumatizing the kids with their exposure to the Holocaust.

My own trauma, acquired growing up in my native Israel among survivors, is making me prioritize instilling in them powerful survival instincts over giving them a sheltered childhood. I can’t know what I would have done as a Jew in Europe in the 1930s. All I can know is that my grandmother was lucky to survive — and I wouldn’t want my children to have to depend on luck.

I also know that, as an Israeli in Europe, I’m OK with my children feeling some discomfort. Maybe exposing my children to the Holocaust early on will give them a nuanced understanding of their home here — a home that is perhaps conditional, even as it is beloved every day.