For Reform, new gay-friendly High Holidays prayer book keeps up inclusivity trend

Published March 22, 2015

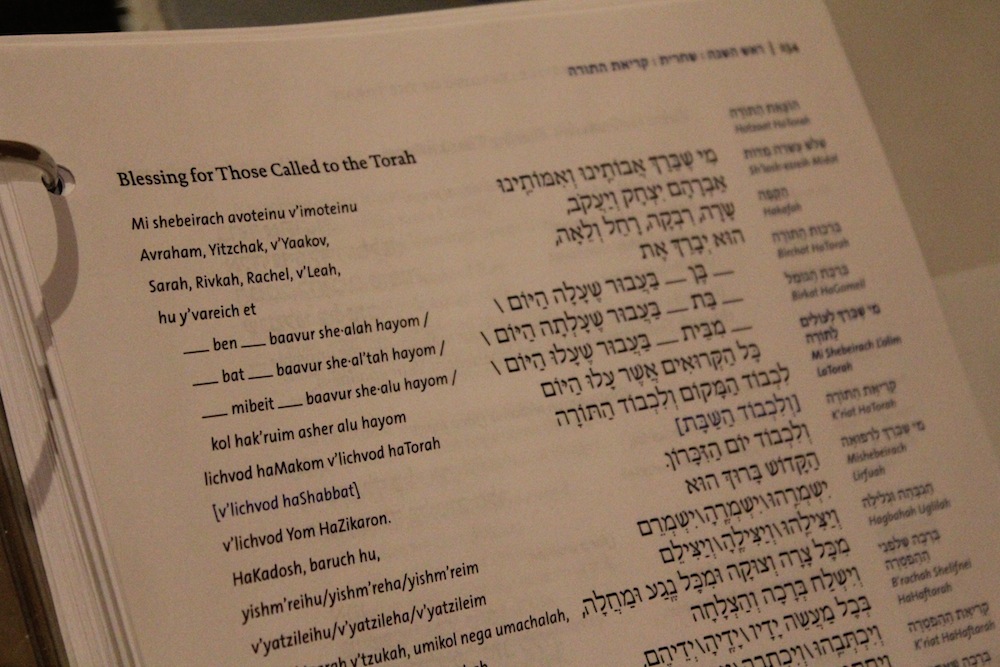

Mockups of the new Reform High Holidays prayer book, Mishkan HaNefesh, on display at the Central Conference of American Rabbis convention in Philadelphia, March 17, 2015. (David A.M. Wilensky)

PHILADELPHIA (JTA) — The Reform movement’s rabbinic association unveiled its new High Holidays prayer book — one that continues the movement’s trend toward inclusive liturgy — at the group’s 126th annual convention.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mishkan HaNefesh, the Reform’s first High Holidays prayer book, or machzor, since 1978, was a major focus of the Central Conference American Rabbis conference that concluded here Wednesday.

The prayer book features the voices of female writers and language more reflective of the LGBT experience. But the volume also signals a return to gendered language for God in Reform liturgy, including a version of the iconic High Holidays prayer Avinu Malkeinu that refers to God as both “Loving Father” and “Compassionate Mother.”

Its title, roughly translated as “sanctuary of the soul,” also refers to the portable sanctuary, or mishkan, that the ancient Israelites carried with them during their desert wanderings. As of last week, 127,000 copies had been preordered by approximately 180 congregations. The first edition of 250,000 copies will be available in June.

“It is spiritual, it weaves the voices of both men and women and contemporary language along with the traditional prayers,” Rabbi Denise Eger, the CCAR’s newly installed president, told JTA. “But it also gives voice and framework to our anxieties and our deep questions about God and meaning and the world in language that the contemporary ear and heart and mind understand.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Published by the CCAR Press, Mishkan HaNefesh has been in the works since the 2007 publication of the regular Reform prayer book, Mishkan T’filah, for which the new machzor is intended as a companion. Both books share the same distinctive two-page layout in which the Hebrew prayers, with their transliteration and translation, are featured on the right side, while the left contains alternative readings drawn from an array of sources. The machzor occasionally departs from this display.

Both books feature the idea of integrated theology, according to Rabbi Edwin Goldberg of Temple Sholom in Chicago, the coordinating editor of Mishkan HaNefesh.

“Integrated theology simply means that there’s many views of God that are normative in Judaism,” Goldberg told JTA. “Some are better known than others. Everything from very theistic, God controls everything to human adequacy, which doesn’t mean there’s no God, but just that so much is up to us. And I think there’s room for a spectrum in a prayer book worship experience.”

This plurality of theologies and perspectives is achieved by including everything from contemporary Israeli poetry to texts for private study and reflection to newly composed prayers that the editors hope will speak to today’s Reform worshippers.

Rabbi Hara Person, the publisher of CCAR Press and executive editor of the new machzor, called one newly composed prayer a “prayer of protest.” Offered as an alternative to Unetaneh Tokef — to many, a perennially troubling prayer with its famous musing about who shall live and die, by fire or by water — the new prayer alternates between frank expressions of doubt and lines from the traditional liturgy.

It reads:

“I speak these words, but I don’t believe them

The Lord God formed man from the dust of the earth.

Clearly there’s no scientific foundation

You know how we are formed;

You remember that we are dust.”

Person says worshippers should feel free to explore the new volume to find what speaks to them.

“We’re saying, yes, absolutely you don’t need to be on the same page as everyone else,” she said. “You don’t need to be on the same page as the rabbi and the cantor. If you find something that inspires you, that moves you, that speaks to you, go for it. That’s fine, especially on the High Holidays, when we’re supposed to be reflecting, meditating.”

The previous Reform machzor, Gates of Repentance, was published in 1978. By the time the process of creating the new prayer book began in 2008, Person said, there was a feeling that the older text was no longer relevant.

“Today we live with different fears and anxieties than we lived with in the ’70s and ’80s,” she said. “There are references in Gates of Repentance to the post-Vietnam era or the fears of nuclear holocaust. Our fears are different. We still have them, but they’re different. I think the Jewish family is understood differently today, who the people in our pews are is understood differently.”

Another impetus for the project was the success of Mishkan T’filah. A survey of movement clergy and congregants about what they sought in a new machzor found that many wanted “a fitting companion” to the new siddur.

“People were fairly used to it at that point and began to, when they went to High Holidays services, they began to feel that Gates of Repentance was this kind of disconnect from their regular worship experience,” Person said.

The new Reform High Holidays prayer book adds a third option to the traditional formula calling worshippers to the Torah to reflect the experience of individuals who don’t identify as male or female. (David A.M. Wilensky)

The new machzor continues the movement’s tradition of inclusivity, replacing a line from Gates of Repentance that referred to the joy of a bride and groom with “rejoicing with couples under the chuppah [wedding canopy].” The machzor also adds a third non-gendered option to the way worshippers are called to the Torah, offering “mibeit,” Hebrew for “from the house of,” in addition to the traditional “son of” or “daughter of.”

The new machzor is a high-stakes endeavor for the movement. Not only is the editorial and publishing process for such works long and costly, but the CCAR relies on prayer books for about 40 percent of its income, according to Person. And since the book is in use only during the handful of days when synagogue attendance is at its peak, it’s a chance for the movement to make a case for its relevance to large numbers of people.

“This is our shot to open their eyes to Reform Judaism,” Goldberg said. “In other words, to show that Reform Judaism isn’t the problem, it’s the solution to the challenges of life.”

![]()